President Biden has been selling his plan to invest in universal pre-school and free community college on international competitiveness grounds, telling a New Jersey audience on October 25, “Any nation that out-educates us will outcompete us.”

Mostly absent from the discussion about expanded access has been talk about testing and accountability. In fact, recent trends in the U.S. have been in the opposite direction. The 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act lowered the stakes attached to nationally mandated state tests. Since then, the gains in student achievement that had been seen under the more rigid No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 have leveled off. The causes of that are debated, but some see a link (see “What to Make of the 2019 Results from the ‘Nation’s Report Card’”).

Colleges are also moving away from the use of standardized testing in admissions (see “Should State Universities Downplay the SAT?” forum, Summer 2020). K-12 school systems are moving away from the use of standardized tests for screening and admissions to selective schools and programs amid the pandemic and heightened concern about racial bias (see “Exam School Admissions Come Under Fire Amid Pandemic,” features, spring 2021).

Some experts are voicing concern that a pell-mell move away from testing could hurt America’s standing, especially as America’s global competitors are moving in the opposite direction. China and India, the world’s two most populous countries, have placed standardized exams at the core of their respective education systems, with the high-stakes Gaokao and CBSE exams determining admission into the two countries’ elite universities. Testing is so sought after by students in both countries that American testmakers see them as potential growth markets. The College Board has sponsored content in one of India’s leading newspapers to promote the Advanced Placement (AP) program and its associated tests as a way to strengthen learning and “conceptual understanding.”

“Not all standardized testing is created equal. But, in the case of instances like the SAT, annual state tests, and gifted admission tests, it’s fair to fear that reducing the role of assessment will have negative consequences,” said Frederick M. Hess, the director of education policy studies at the center-right American Enterprise Institute. How worried people should be, he said, depends on “what the replacement looks like, and how aware decision-makers are of the risks.”

Hess, an executive editor of Education Next, was a member of a 2012 Council on Foreign Relations task force on U.S. Education Reform and National Security that concluded “Educational failure puts the United States’ future economic prosperity, global position, and physical safety at risk.” In 2012, standardized testing was under some pressure, but the pandemic and the recent push for racial equity have accelerated the move away from testing since then.

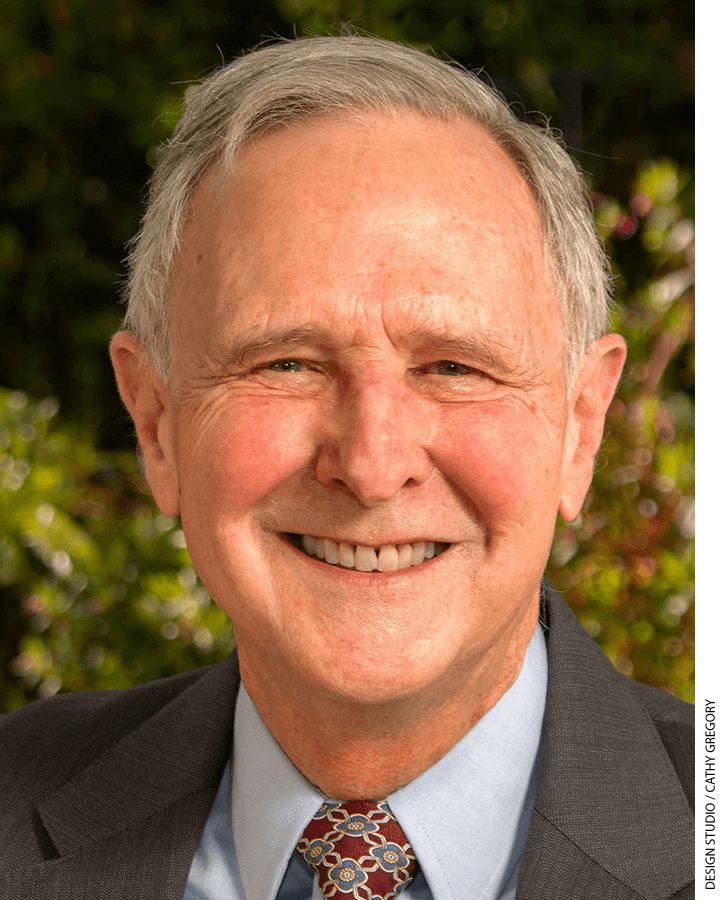

Chester E. Finn, Jr., a Department of Education official during the Reagan administration who is president emeritus of the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, wrote recently, “As other countries’ children surpass ours in core skills and knowledge, we face ominous long-term consequences for our national well-being, including both our economy and our security. But what’s even more worrying than the achievement problem is the loss of will to do much about it and the creative ways we’re finding to conceal from ourselves the fact that it’s even a problem.”

When asked about how the elimination of standardized testing would affect the United States, Finn said in an interview that he thinks “the United States will be worse off over time, but it would be a number of years before we saw the damage, and by then, the decline will be very hard to reverse.” He also noted that “people in the United States are now competing with people from all around the world,” and that the country’s past economic competitiveness was driven by the fact that “we simply had more education than anyone else, but this is no longer the case, even when just looking at high school graduation rates.”

Education has already been shown to be an important determinant of countries’ economic outcomes. A senior fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution, Eric Hanushek, was recently awarded the 2021 Yidan Prize – the world’s most prestigious prize in the field of education – in part for his research on this topic. Hanushek and his co-authors found that long-run growth in nations’ GDP is largely shaped by the skills of their populations, which, in turn, is something that can be measured by standardized, international assessments focusing on mathematics and science. Hanushek said in an interview that “various tests have shown that education in the United States is below average in comparison to other wealthy countries,” showing a need for action. He also notes that while testing and test results often do not directly lead to policy changes in the United States, they can still “influence actions at the individual level, with both parents and schools that want better performance paying attention and responding to poor test scores.” In other words, standardized tests not only provide a measure of the problem at hand, but also serve as a call to action for those who are most concerned with — or most connected to — the problem.

Throughout the United States, efforts are underway to eliminate or substantially reduce the role of standardized testing at all levels of the education system. According to FairTest, a research and advocacy organization that works to reduce the use of standardized testing, nearly 1,800 four-year U.S. colleges and universities will not require standardized tests for the 2022 admissions cycle, while 85 will not consider test scores even if students choose to submit them. Even the College Board, which administers – and derives most of its revenues from – the SAT exam and the Advanced Placement program, has decided to stop offering SAT Subject Tests, which previously allowed students to demonstrate specialized knowledge in various subjects to enhance their college applications.

This trend is also prevalent at the state and local levels. Earlier this year, the University of California system announced that it would permanently stop considering SAT and ACT scores for admissions, while San Francisco replaced an exam with a lottery for admission to the city’s prestigious Lowell High School. Similarly, New York City and Boston have both recently engaged in extensive political conversations around removing standardized exams from the admissions process for selective high schools. Boston officially decided to permanently reduce the exam’s weight by 40 percent while simultaneously moving away from a purely grades- and exam-based system of ranking prospective students.

The movement away from standardized testing is rooted in the notion that standardized tests are inherently unfair measures of student achievement and potential, and thus, should not be used in judging students, much less in determining admission into selective universities.

The interim executive director at FairTest, Robert Schaeffer, said in an interview that “standardized tests should not be the sole or primary factor used to make high-stakes decisions,” and alluding to the argument that such tests do not align with curricula, says that “teachers’ assessments of students, which are based on the material being taught in classrooms, should be given the heaviest weight.”

From a more practical standpoint, Nicholas Lemann, a professor at Columbia University and author of the 1999 book The Big Test, told me that “at selective universities, of which there are only 50 or so out of thousands, the admissions criteria have never been fully academics-based, but even if they were, there is enough data from sources like high school transcripts and AP tests to evaluate students.”

Historically, the international competitiveness argument—both on national security and on economics—has worked domestically to drive education legislation, investment, and reform.

When the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, America responded with the 1958 National Defense Education Act, which channeled funding with a focus on math and science to colleges and universities. The 1983 report “A Nation at Risk,” observed, “We live among determined, well-educated, and strongly motivated competitors. We compete with them for international standing and markets.” It went on, “The risk is not only that the Japanese make automobiles more efficiently than Americans and have government subsidies for development and export. It is not just that the South Koreans recently built the world’s most efficient steel mill, or that American machine tools, once the pride of the world, are being displaced by German products. It is also that these developments signify a redistribution of trained capability throughout the globe.” That report helped build the case for state-by-state comparisons as part of the “nation’s report card,” or National Assessment of Educational Progress.

Recent headlines echo in some ways the concerns of the late 1950s and early 1980s. The chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, General Mark Milley, said in a Bloomberg Television interview with David Rubenstein that China’s recent test of a hypersonic missile was “very close” to a “Sputnik moment.” The Commerce Department recently announced that the U.S. trade deficit in goods and services had hit a record high, measured on a monthly, seasonally adjusted basis. Some also view India as posing a substantial economic threat. Though India’s public education system is troubled, there are boarding schools serving the country’s elite, and the prestigious Indian Institutes of Technology train highly skilled engineers. In particular, Indian nationals reportedly receive approximately 70 percent of all H1-B visas, which the U.S. grants to high-skilled foreign workers, the vast majority of whom are hired for jobs in STEM. The program requires employers to certify that American workers can’t be found to fill the positions.

The CIA is reorganizing to combat what the CIA director calls “the most important geopolitical threat we face in the 21st Century, an increasingly adversarial Chinese government.” Will the U.S. education world also adjust to these contemporary developments? Or will anti-test stances gain further traction? Eliminating accountability testing will leave the United States without a gauge of how much its students have learned – a fact that is often ignored by those claiming that eliminating exams will lead to better outcomes.

Lemann says that backing off the use of standardized tests for college admissions might actually not be that significant: “the overwhelming majority of bachelor’s degree-granting institutions in the United States are not highly selective, so eliminating standardized tests would only affect the selection of elites – and even then, only marginally, because of the vast amount of other academic data that is available.” Finn, though, said, “there are not many elite universities, but the few that do exist are highly regarded in the U.S. and around the world, so their admissions processes matter a lot.”

At the K-12 level, alternatives to standardized testing, such as teacher-issued grades, school inspections, or community surveys, all have their own drawbacks. Despite the high-profile recent victories of anti-testing advocates, surveys, including the Education Next survey of public opinion, show strong and consistent support among the general public, for a continuation of the federal requirement of annual testing in math and reading.

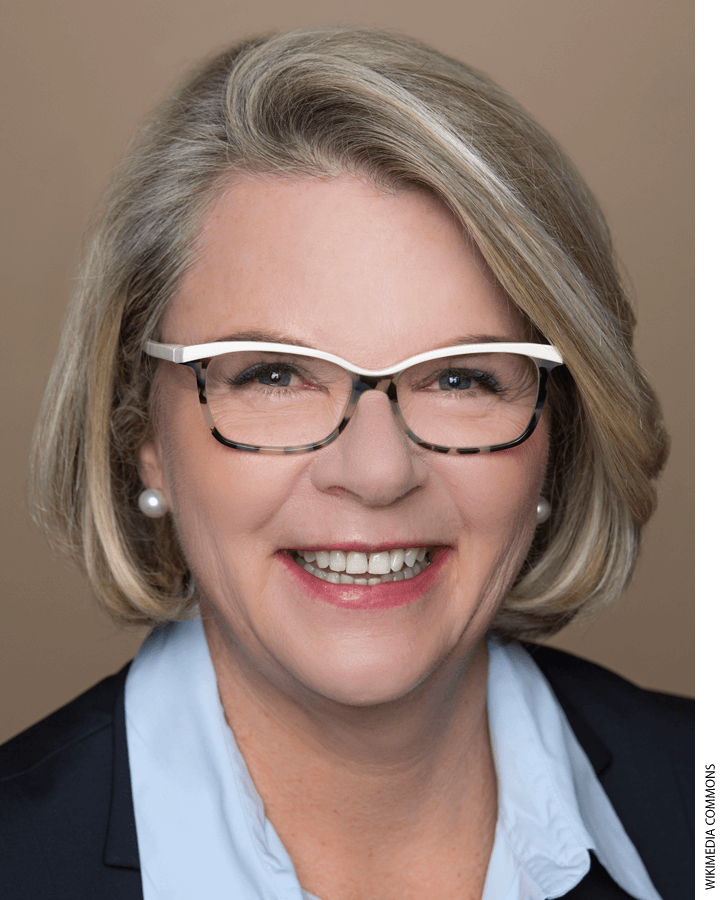

That support is sufficiently strong that some experts, such as a Margaret Spellings, who served as Secretary of Education in the George W. Bush administration, downplayed the risk that America will abandon testing wholesale, rather than just make needed adjustments in places where it’s been clumsily used. Spellings noted in an interview that the current Secretary of Education, Miguel Cardona, has not been anti-testing. After taking office, Cardona told states they needed to administer annual tests notwithstanding the pandemic, declining some requests to waive the testing requirement. Spelling told me she is “confident that the United States will not move away from using assessments to gauge student achievement.” For the sake of the country’s global competitiveness, let’s hope she’s right.

Yanxi Fang is a student at Harvard College concentrating in government.

The post Testing Backlash Could Hurt American Global Competitiveness appeared first on Education Next.

[NDN/ccn/comedia Links]

News…. browse around here

No comments:

Post a Comment