In February, before the coronavirus pandemic upended the nation’s education system, Georgia’s Republican governor, Brian P. Kemp, announced plans to cut state-mandated high school end-of-course tests by half, confine state elementary and middle school testing to the last five weeks of the school year, shorten tests, and encourage school districts to work with the state’s education agency to reduce local testing. “When you look at the big picture, it’s clear,” Kemp declared. “Georgia simply tests too much.”

Governor Kemp’s announcement expressed a backlash against standardized testing in public education that has left the future of state testing, a cornerstone of school reform for nearly three decades, in doubt.

Pressure to reduce testing has come from many, often confounding sources: teachers’ unions and their progressive allies opposed to test-based consequences for schools and teachers; conservatives opposed to what they consider an inappropriate federal role in testing; suburban parents who have rallied against tests they believe overly stress their children and narrow instruction; and educators who support testing but don’t believe current regimes are sufficiently helpful given how much teaching time they consume.

School reformers and state and federal policymakers turned to standardized testing over the years to get a clearer sense of the return on a national investment in public education that reached $680 billion last year, to spur school improvement, and to ensure the educational needs of traditionally underserved students were being met. Testing was a way to highlight performance gaps among student groups, compare achievement objectively across states, districts, and schools, and identify needed adjustments to instructional programs.

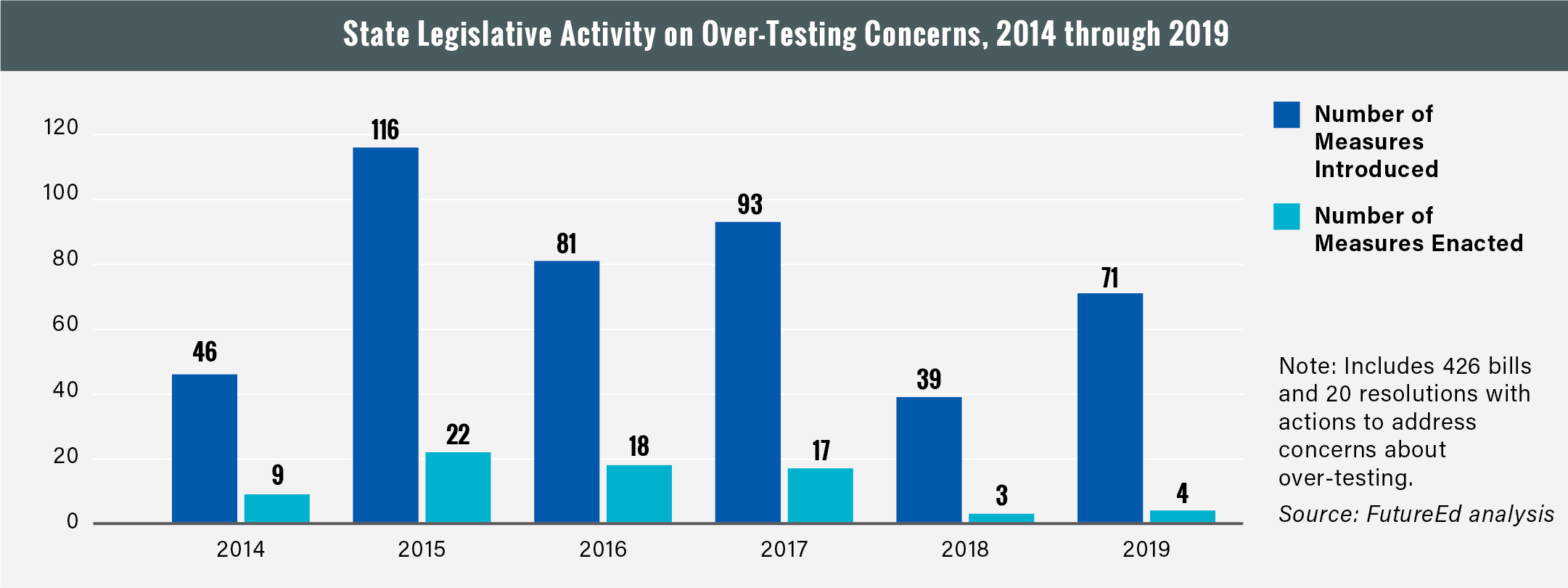

But the pushback against testing in recent years has led to a substantial retreat on testing among state policymakers. A new national analysis by FutureEd has found that between 2014 and 2019, lawmakers in 36 states passed legislation to respond to the testing backlash, including reducing testing in a variety of ways, a direction also taken by many state boards of education and state education agencies.

Likely Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden expressed concerns about standardized testing during a national debate in December. And in the wake of mass school closures due to the coronavirus pandemic, U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos announced on March 20 that her department would waive federal standardized testing requirements for the 2019-20 school year in states requesting testing relief. The move, and the consequent loss of a year’s worth of longitudinal data, could further reduce the standing of state tests. The chances are strong that there won’t be any end-of-year state testing anywhere in the nation for the first time in half a century.

Already, teacher union leaders, like the president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association, are signaling the suspension could provide an opening to cancel the state tests permanently. In a Facebook post, the union president, Merrie Najimi, wrote, “Onward to cancelling MCAS PERMANENTLY and reclaiming our schools as joyful places, where our curriculum returns to being developmentally appropriate as it was before we were shackled by MCAS, and where ALL kids can have their recess back since they won’t have to spend their days preparing for MCAS.”

Given the testing climate in recent years, the federal Every Student Succeeds Act has become a bulwark against further reductions in the measurement of school performance, even as DeVos suspends the law’s requirements for 2019-20. The law requires that every state test every student in seven grades annually and report the results in a way that bars school districts from masking the performance of disadvantaged students.

But a close analysis of the political landscape of standardized testing makes clear that unless a new generation of tests can play a more meaningful role in classroom instruction, and unless testing proponents can reconvince policymakers and the public that state testing is an important ingredient of school improvement and integral to advancing educational equity, annual state tests and the safeguards they provide are clearly at risk.

Toward Transparency

Before the 1960s, states had scant information about how well their students were performing. But in 1965, as part of the War on Poverty, the federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act poured millions of dollars into schools and required studies of the impact of those funds. In 1969, Congress mandated a federally funded snapshot of student performance, the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

State governments, meanwhile, began requiring tests to determine if students were making progress in core subjects. Michigan launched the first statewide testing program, also in 1969. But there were no state achievement standards for how well students should perform and no explicit consequences for schools if students performed poorly.

In the 1970s, concerns about the performance of high school students, in particular, led to the “minimum competency” movement and expanded state testing to ensure students graduated with the requisite basic skills. By the 1980s, there was growing alarm about student performance as the nation transitioned to a knowledge-based economy. Gaps in the achievement of long-neglected student populations gained prominence in the wake of the civil rights movement. The concerns spurred the publication of A Nation at Risk and a host of other reform manifestos that urged a more demanding curriculum and more rigorous graduation requirements for every student.

In the ensuing years, policymakers became increasingly frustrated as local districts watered down those requirements with courses like “business math” and “the fundamentals of science.” So, in the late 1980s and 1990s, Republican and Democratic presidents, as well as the nation’s governors, began to push for higher educational standards and national goals, as well as more student testing and efforts to hold schools and districts accountable for results. The Clinton Administration’s reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act in 1994 required states, for the first time, to adopt state standards that would be the same for all students and to test all students’ progress against those standards in at least three grades.

But not all states responded to the requirements with equal rigor. When George W. Bush took office, he decided to place significantly more emphasis on tests and test results in the next reauthorization of the law, with the goal of ensuring that the needs of students furthest from opportunity were being addressed. The federal No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 mandated that states test every student every year in reading and math in grades 3-8 and once in high school, and test them in science at least once in elementary, middle, and high school. NCLB also required states, districts, and schools to publicly report test data by race and income. And it set strict timelines for schools to get every student to the proficient level on state tests or face an escalating series of supports and sanctions. The law effectively tripled the size of the state testing market over the six years after it was passed.

The increased requirements reflected a belief that for every child in America to achieve high standards, schools needed to track the learning of every student every year against those standards and be held accountable for the results—a fight against what then-President Bush called “the soft bigotry of low expectations.” National leaders simply didn’t trust local educators to do the right thing for low-income students and students of color, so they tried to force them to act, in part, by imposing far more transparency and accountability via testing.

“It has been clear to the civil rights community for a very long time that without comparable, annual statewide assessments, it is very difficult to know whether there is equal opportunity in education,” said Liz King, director of Education Policy for the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. “Even if you don’t care about equity or remedying discrimination, I think there are a lot of people who care about knowing whether the education system is working, whether expenditures are supporting the outcomes that families expect.”

But if NCLB was designed to shed a bright light on educational inequities, states, districts, and schools frequently responded to that pressure in ways that jeopardized student learning and kindled anti-testing sentiment. Schools emphasized instruction in tested subjects at the expense of untested subjects and stressed test-taking skills. School districts piled on new benchmark tests to gauge how students would perform on end-of-year exams. States began to rely heavily on simplistic multiple-choice tests because they were cheaper and easier to administer in the face of NCLB’s tight testing timelines. And many states lowered their testing standards to get more students over the proficiency bar.

The Backlash Builds

Many states’ indifferent commitment to higher standards and counterproductive responses to NCLB led national leaders to push harder. In 1996, a bipartisan group of governors and business leaders had founded an organization called Achieve to help states ensure all students graduated high school ready for college and careers. In 2001, the same year that NCLB became law, a group of states began collaborating with Achieve to identify the “must have” knowledge and skills needed by higher education and employers. The work laid the foundation for a 2009 agreement by the National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers to jointly develop demanding voluntary standards in English language arts and math—what became the Common Core State Standards.

As a result, the two organizations were finishing work on the Common Core standards at the same time the Obama administration was drafting the Race to the Top initiative, which provided billions of dollars in education funding to states to help address the 2008-09 economic crisis.

Governors asked that states be allowed to use some of the federal funding to implement the Common Core and to develop aligned tests, an expensive undertaking. In the end, the $4.35 billion Race to the Top competitive grant program incentivized states to adopt tougher academic standards and more rigorous tests aligned with those standards, by making the grants contingent on states adopting the reforms.

Spurred in part by the prospect of federal largesse, most states quickly embraced the Common Core standards and they joined one of two voluntary state consortia to develop Common Core-aligned tests with federal funding, the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium and The Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers.

The Obama administration also made competitive Race to the Top grants contingent on states creating new teacher evaluation systems that judged teachers “in significant part” on the basis of their students’ test scores, even though the tougher standards and tests wouldn’t be fully in place before the new evaluation systems were launched—a demand that Kate Walsh, the director of the National Council on Teacher Quality and a proponent of the move at the time, now calls “a strategic blunder.”

The administration’s decision to leverage billions of dollars in federal funding on behalf of higher standards, harder tests, and test-based consequences for teachers brought the national teachers’ unions and Tea Party conservatives to the barricades, if from opposite directions. The Tea Party and its Republican congressional allies condemned the Common Core as a federal usurpation of traditional local control in public education (even as state organizations led the development of the new standards). The unions targeted the new teacher evaluation systems and the increase in teacher accountability they represented, spurred by rank-and-file members outraged that their livelihoods suddenly depended on how well their students performed on brand new standards and tests.

In 2014, the three-million-member National Education Association launched a national “Campaign to End ‘Toxic Testing’” that would “seek to end the abuse and overuse of high-stakes standardized tests and reduce the amount of student and instructional time consumed by them.”

The NEA and the American Federation of Teachers pumped millions of dollars into state lobbying campaigns. They channeled money to outside organizations like FairTest to attack testing. And they launched grassroots efforts to encourage parents and their children to boycott state testing.

In 2015, the NEA’s Maryland affiliate launched a “Less Testing, More Learning” campaign to scale back testing and water down accountability—a lobbying blitz that included 50,000 e-mails, 4,000 phone calls, and 2,000 letters and postcards from MSEA members to their representatives, working alongside groups like the PTA, the ACLU, and the NAACP, organizations that have championed the reporting of test data by race and class to uncover educational inequities, but have opposed the use of state tests to make high-stakes decisions about schools and students, often out of concern about racial bias in standardized testing.

“I would urge parents…to opt out of testing,” Karen Magee, the then-president of New York State United Teachers, told an Albany public affairs show in 2015, after thousands of vocal parents and students, many of them in more-affluent suburban school districts, refused to take New York’s standardized tests on the grounds that the tests were too long, too stressful, and sidetracked instruction.

As the opt-out movement spread, generating a squall of sensational headlines, the U.S. Department of Education was compelled to warn a dozen states that they risked federal sanctions for not having enough students take their standardized tests.

At the same time, several book-length critiques of testing added fuel to the anti-assessment fires, including The Test: Why Our Schools Are Obsessed with Standardized Tests, by Anya Kamenetz, an NPR reporter; The Testing Charade, by Daniel Koretz, a professor emeritus at the Harvard Graduate School of Education; and Beyond Test Scores, by Jack Schneider, an assistant professor in the college of education at University of Massachusetts-Lowell.

The Obama Administration Retreats

The avalanche of opposition forced the Obama administration to retreat on testing. In August 2015, U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan announced in the blog post “Listening to Teachers on Testing” his department’s decision to grant states with NCLB waivers a one-year delay in incorporating scores into teacher evaluations. Duncan, who had pressed for test scores to be part of Race to the Top teacher evaluations, said he shared teachers’ concerns that “testing—and test preparation—takes up too much time.”

Even so, testing opposition remained strong, and the White House pressed for a more substantial response after the president told his advisors that testing was coming up in conversations as he traveled the country. In October, the administration announced a Testing Action Plan “to correct the balance” between the “vital role that good assessment plays … while providing help in unwinding practices that have burdened classroom time or not served students or educators well.” The administration announced grants for state and local testing audits, based on the recognition that state- and district-required tests, many of them not mandated by the federal government, had piled up over time and lost their strategic value. The administration also recommended that states cap the percentage of instructional time students spend taking required statewide standardized assessments, “to ensure that no child spends more than 2 percent of her classroom time taking these tests.”

That same month, the Council of Chief State School Officers and the Council of Great City Schools, representing the nation’s large urban school districts, announced a joint project to throw “their collective weight behind an effort to reduce test-taking in public schools, while also holding fast to key annual standardized assessments.”

In December 2015, the president signed the federal Every Student Succeeds Act, which replaced the No Child Left Behind Act. The new federal law gave states and districts far more power to craft their own education solutions than they had wielded under NCLB.

State Legislators React

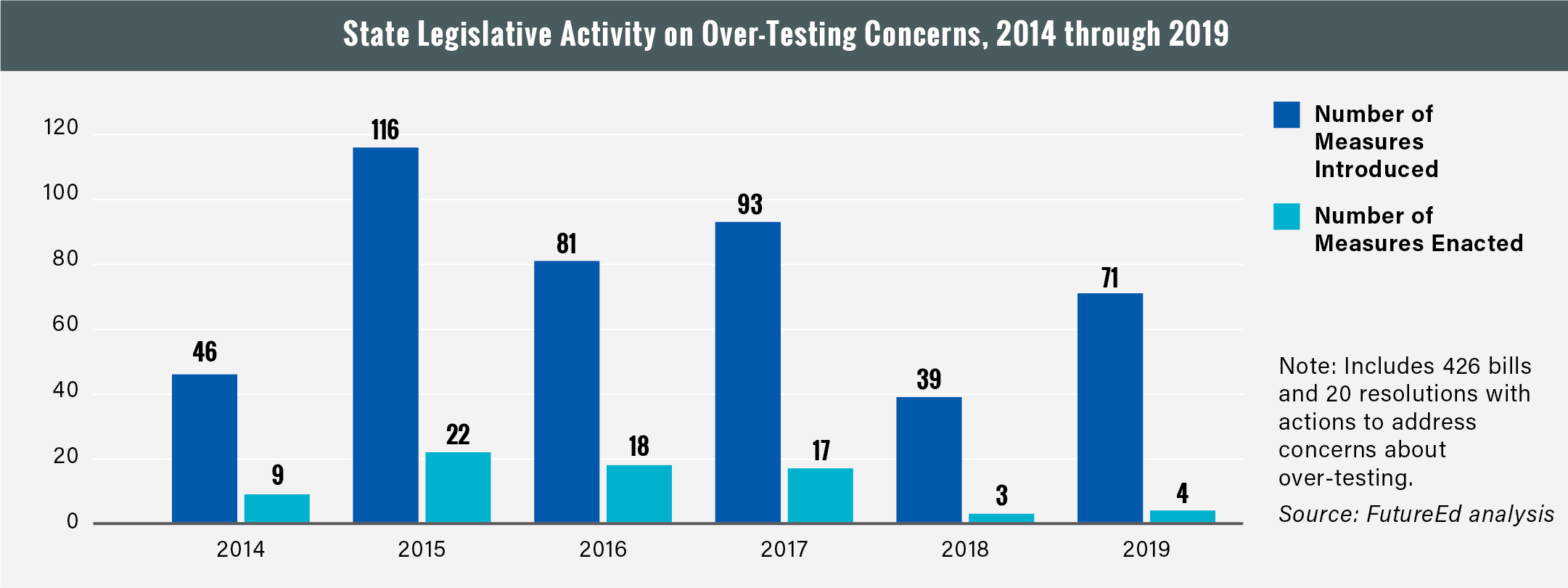

State legislators responded to the testing backlash and the easing of federal mandates with a wave of legislation to restrict testing within their borders. FutureEd conducted a comprehensive analysis of state legislation and resolutions from 2014 through 2019.

Lawmakers introduced 426 bills and 20 resolutions in 44 states in response to critics’ claims of over-testing. Measures were adopted or enacted in 36 states. There were more bills in 2019 than in 2018, an indication that anti-testing sentiment remains strong in state capitals five years after the signing of the Every Student Succeeds Act. This is especially true in southern states such as Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Brian Kemp’s Georgia.

The FutureEd analysis excludes dozens of parental “opt out” bills that in most instances granted students unrestricted rights to sit out state tests. And it doesn’t reflect moves to reduce testing in many states in recent years by governors, state boards of education, and state departments of education.

Lawmakers’ most common legislative response was to reduce the number of state tests students must take. In other instances, they shortened the length of tests, capped standardized testing time in schools, required public reporting of testing time, or directed state agencies or local school districts to limit testing.

A quarter of the 167 bills to reduce state testing demanded the discontinuation of every test not required by the federal Every Student Succeeds Act and the No Child Left Behind Act before it. Others targeted tests in grades and subjects not covered by ESSA—particularly social studies. More than half the test-reduction legislation involved at least some social studies tests or high school exams in social sciences such as history. And half targeted high school end-of-course tests.

North Carolina’s Testing Reduction Act of 2019, signed into law by Democratic Governor Roy Cooper, captures today’s state testing climate. The legislation eliminates nearly two dozen statewide exams used primarily for teacher evaluations. It directs the North Carolina department of education to report the numbers and types of state and local tests every year and publish state and local testing types/calendars on the agency’s website. It compels local school boards to cut local standardized testing if the number of tests or hours of testing exceed the state’s two-year average. And it establishes the intent of the North Carolina legislature to move away from a single long testing event at the end of the year and toward multiple short testing events throughout the year.

Policymakers’ pushback against testing is reflected in recent declines in state testing sales after years of expansion. The market shrank by 3.5 percent from 2017-18 to 2018-19, according to a recent analysis by Simba Information, a marketing research firm. “The pendulum has swung from developing new tests to reducing the number of exams that are required and shortening the length of existing exams,” according to Simba.

FutureEd’s analysis confirmed the bipartisan nature of the legislative action against standardized testing. Sixty-eight of the measures enacted between 2014 and 2019 were sponsored by individuals rather than legislative committees. Of those, Republican legislators authored 41 percent, Democrats authored 44 percent, and 15 percent were bipartisan.

In addition, some states have backed away from using student test scores to rate teachers since the 2015 passage of ESSA. The National Council on Teacher Quality reports that 26 states now use results from state standardized tests as part of their teacher evaluation systems, down from 37 states in 2015.

Teachers’ take on testing is complex. In general, teachers want measures of student progress and support standardized testing, but many don’t think the existing tests are doing the job, particularly when it comes to informing instruction and reflecting their curriculum.

Teacher union leaders are forthright about not wanting their teachers held accountable for their students’ achievement on standardized tests, and about their opposition to high-stakes school accountability more generally. That’s why they often sided with the opt-out movement. “We have actually pushed for appropriate testing and we’ve pushed for reductions of extraneous tests, extraneous paperwork,” Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, says. “The reason we were part of the opt-out movement, in some places, was because of the high-stakes nature of standardized testing. It wasn’t a snapshot to see where kids were at any point in time … Basically, there was a fixation on the teachers and the consequences for the teachers rather than a fixation on what children needed.”

Weingarten says she leans toward the type of sample testing in key grades that many high-performing countries use and away from testing every student every year, as required under ESSA—a move that would reduce transparency into school performance and eliminate the use of test results in teacher evaluations. The National Education Association advocated for such a shift during congressional drafting of ESSA.

A Tale of Two Tests

One reason for the perception that there’s too much state testing is that both parents and the public more generally often conflate state-mandated testing with the many interim, benchmark, and diagnostic tests that school districts deploy. Even as policymakers decrease time devoted to state testing, it’s difficult to rein in local assessments, which comprise an increasing share of the testing market, according to Simba.

“When we asked teachers, ‘What would you get rid of?’ they wanted to get rid of the state assessment because they didn’t find the state assessment immediately useful to their instruction,” says Rachel Cantor, executive director of Mississippi First, a state education advocacy group. “But the state assessments are not what actually takes all their time. It’s district assessments.” For their part, “Parents make no distinction whatsoever between state tests, district tests, teacher-made tests,” Cantor says. “It’s all just, ‘Why do you have so many tests?’”

Studies have found that the average classroom spends about 2 percent of instructional time taking mandated tests, a small fraction of the school year. But some schools and school districts spend much more, contributing to perceptions of “over-testing.” A 2014 study of a dozen urban districts by the non-profit organization Teach Plus found that test-taking ranged from three days in one district to two weeks in another. Test preparation ranged from 16 to 30 school days. The report was especially critical of the time spent on low-quality local benchmark tests that were often misaligned with state standards.

An inventory of standardized testing in 66 urban districts the following year by the Council of Great City Schools found that testing was most prevalent in the eighth grade, where students spent just over 2 percent of school time taking standardized tests. To the council’s executive director, Michael Casserly, the biggest problem wasn’t excessive testing time. It was results that weren’t coherent and useable: “I haven’t seen a lot of states, or anybody else, ask themselves the question, ‘Does this portfolio of standardized tests we’re using really measure what we want to have measured?’”

The Obama administration funded the development of the PARCC and Smart Balanced tests to address the mismatch between higher standards embodied in the Common Core and the superficiality of the standardized tests that emerged in many states under NCLB, though the consortia tests were typically longer than the tests they replaced. So as states abandon the consortia assessments, the risk of tests driving down classroom standards is reemerging.

A New Testing Landscape

The contours of a new generation of statewide standardized testing that promotes both accountability and instructional improvement has emerged from the testing debates of the past several years and from teacher surveys.

Teachers identify “capturing student learning over time, rather than a single snapshot at the end of one year” as a key way to make standardized testing more useful. Georgia, Louisiana, New Hampshire, and North Carolina are piloting moves in that direction under the federal Innovative Assessment Demonstration Authority, exploring ways to give more frequent, instructionally useful assessments that can roll up into a summative, year-end score. Similarly, Nebraska is working with the testing company NWEA to roll up the state’s computer-adaptive tests, given periodically throughout the year, into a cumulative result. In January, the U.S. Department of Education proposed to expand experimentation by increasing federal funding for such work.

To Emma Vadehra, former chief of staff at the U.S. Department of Education during the Obama administration, that means developing more helpful tests, but also new measures to be used alongside tests in gauging school performance and supporting teachers’ work. Teachers agree. More than 7 in 10 teachers in the Educators for Excellence survey favored multiple measures of school performance that included district or state standardized tests.

The Every Student Succeeds Act incentivizes states to develop new measures by requiring them to include non-academic factors in judging schools’ performance. So far, 36 states have added student absenteeism to their accountability systems, making it by far the most popular measure. A dozen states have moved toward measuring school climate and student engagement through annual surveys of students, teachers and parents, in some cases holding schools accountable for the results. Though researchers warn that surveys shouldn’t yet be deployed in that way, school climate and student engagement are emerging as important aspects of student success.

Meanwhile, the layering of many local tests on top of state testing regimes, and the conflating of state and local testing in the minds of many parents and policymakers, points to the importance of more effective coordination on standardized testing between state and local education leaders. This could help reduce the level of standardized testing in the nation’s classrooms. As the executive director of the Michigan Assessment Consortium, Ed Roeber, put it: “States, with the cooperation and collaboration of local districts, need to develop systems of assessment that balance the state program with assessments that actually help kids learn.”

Ary Amerikaner, a former Obama administration education official and now a vice president at the Education Trust, also points out that school improvement continues to be a component of federal standardized testing mandates under ESSA, and “that requires actually getting the school-improvement side of state accountability systems right.” Emerging tests and testing systems also need to be developed with much more teacher involvement than has been the case so far. Testing systems must also stay attuned to the needs of parents, who tend to value their children’s progress more highly than the performance of the school systems they live in or even the schools their children attend.

A Race Against Time

There is not a tremendous amount of time to address these challenges.

The Georgia governor’s recent move to slash the state’s testing system suggests the issue is very much alive among conservative policymakers. Testing critics on the left have kept up a relentless drumbeat against high-stakes testing, supported in recent months by Democratic presidential candidates Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, as well as by Biden.

Given the political gridlock in Washington and the current pandemic, it’s likely to be several years before ESSA is reauthorized. But the depth and breadth of the backlash against statewide standardized testing in recent years and the attacks on testing from both the left and the right suggest there’s a real chance that Congress could abandon the ESSA testing mandate when it next rewrites the law. That, in turn, could mean the end of annual statewide testing in many parts of the country and an end to the transparency and civil rights protections it was designed to produce.

That leaves school reformers in a race against the clock to create testing systems that are more valuable to educators and parents and that offer meaningful windows into school and student performance without overwhelming teachers and principals.

Adapted from the FutureEd report, The Big Test: The Future of Statewide Standardized Assessments.

By: Lynn Olson

Title: Statewide Standardized Assessments Were in Peril Even Before the Coronavirus. Now They’re Really in Trouble. – by Lynn Olson

Sourced From: www.educationnext.org/statewide-standardized-assessments-were-in-peril-before-coronavirus-bipartisan-backlash/

Published Date: Tue, 21 Apr 2020 04:01:59 +0000

The CEO of Chiefs for Change, Mike Magee, joins Education Next Editor-in-chief Marty West to discuss how schools are responding to challenges posed by the novel coronavirus.

The CEO of Chiefs for Change, Mike Magee, joins Education Next Editor-in-chief Marty West to discuss how schools are responding to challenges posed by the novel coronavirus.