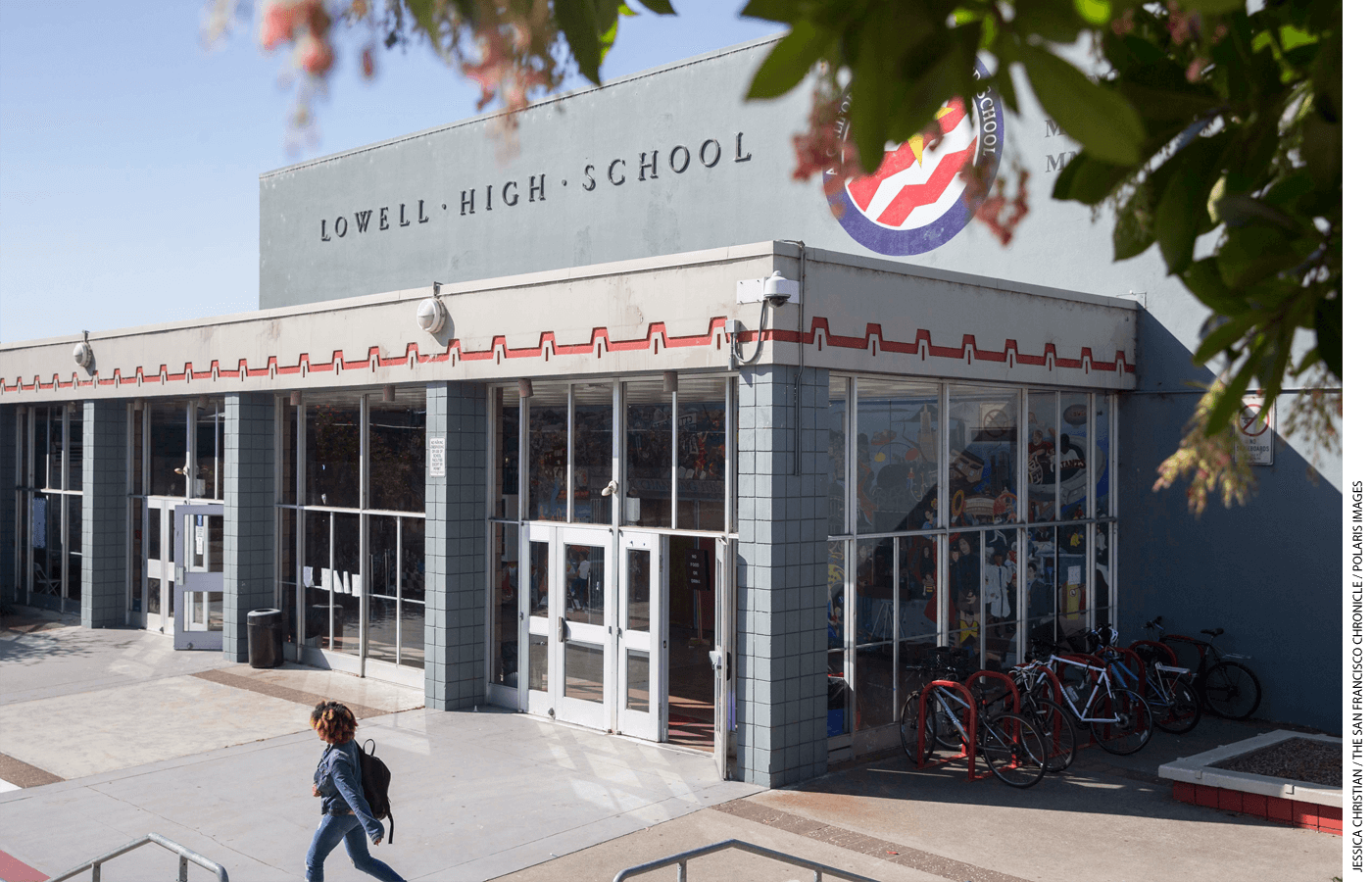

Lee Cheng graduated from San Francisco’s Lowell High School in 1985. He counts himself one of the lucky ones. Lowell High, which was the only local public school specifically for high-performing students, had a strict racial-quota admissions policy when he applied. No racial or ethnic group could comprise more than 40 percent of the school’s student body. The rule was aimed at desegregating the district, but even as a teenager, Cheng found it unfair. It meant that Asian students had to score higher on the entrance exam than white students, who in turn had to score higher on the exam than Black and Hispanic applicants. Cheng’s friend—his orchestra partner—was not admitted, though if he had been of a different race he might have earned a seat. The boy’s parents were poor immigrants—his father a waiter and his mother a seamstress. “He would have gotten in, but for being Chinese,” Cheng said.

Years later, after Cheng graduated from Harvard, he and several of his former classmates from Lowell joined a federal class-action lawsuit against San Francisco over the policy, Ho v. San Francisco Unified School District. After five years of litigation, the district agreed to a settlement and abolished its race-based admissions. Instead of adopting a single standard, Lowell tried a variety of systems to achieve the racial balance it sought. In 2001, it adopted a three-band approach. Seventy percent of students were admitted on the basis of their test scores and grades. Another 15 percent were admitted on a combination of those factors plus some more holistic considerations such as community service and demonstrated ability to overcome hardship. The remainder of the students were selected from underrepresented schools.

In October 2020, that system ended—perhaps temporarily, but in all likelihood permanently. Because of the coronavirus pandemic, all of the students in San Francisco public schools received only pass-fail grades in the spring semester of the 2019–20 school year, and the exam for admissions was never administered. In the spring of 2021, applicants will be chosen for Lowell with the same formula used at other schools in the city—some combination of lottery, sibling preference, and geography. Covid-19 may have provided the impetus for the change, but the new policy also plays into a political phenomenon: in the past few years, pressure has been building for the city to reconfigure the school’s student body so that it more accurately mirrors the racial composition of the city.

Lowell is not alone among the specialty schools, known as exam schools or magnet schools, in deciding to change its admissions standards this year. According to a survey conducted by Chester Finn and Jessica Hockett for their 2012 book Exam Schools, there are about 165 stand-alone public high schools with selective admissions processes in the United States. Some of the biggest and most renowned of them are currently undergoing existential debates. Boston will not be administering the test it previously required for admission to its three academically competitive schools. In Fairfax County, Virginia, the district has announced plans to eliminate the test for Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology and admit students from a lottery of applicants who have at least a 3.5 GPA and a year of algebra. And in New York City, parents anxiously awaited an announcement for almost a year about the test date for Stuyvesant, Brooklyn Tech, and Bronx Science, three schools whose entrance is determined entirely by test scores. Admission to other “screened schools” in the city that use the same exam but also judge students on other criteria was altered to eliminate preference for students who live near the schools, and there is still a possibility that the test for those schools will be abolished.

While the leaders of all four of these school systems assert that the pandemic-driven modifications are temporary, they face tremendous pressure by activists and political leaders to make long-term changes to their admissions policies because the student populations of the specialty schools do not reflect the racial composition of the areas where they’re located. In some cases, that pressure is likely to result in permanent changes that would fundamentally alter the character of these schools. Indeed, the Covid crisis seems to have provided an ideal opportunity for activists, school administrators, and politicians to effect the systemic transformation they have been pushing for years.

Lowell High School in San Francisco

The proposed change at Lowell, a school of about 2,700 students whose graduates include Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, comedian Carol Channing, and novelist Jennifer Egan, was announced with little fanfare the Friday before Columbus Day weekend in 2020. The San Francisco Board of Education met the following Tuesday to hear public comment about the proposal. At the five-hour Zoom meeting, which was recorded, the board set aside one hour—30 minutes for those who supported the change and 30 for those who opposed it—with each speaker given 60 seconds before his or her microphone was cut off. The opposition included parents, students, and alumni. A number of speakers wondered why the decision seemed so rushed. Others asked why grades from previous years couldn’t be used as a factor in the application process.

The supporters of the change spoke not only about the small percentage of African American students at Lowell but also about their experiences of racism there. In February 2016, about two dozen of the school’s Black students walked out of school and marched to city hall to protest a Black History Month poster created by a non-Black student. The poster featured rappers and a picture of President Barack Obama wearing a diamond stud earring, as well as the hashtag #gang.

At the October 2020 school-board meeting, Shavonne Hines-Foster, one of two student representatives on the board, spoke immediately after the public comment period. A Black student at Lowell, she decried the “privilege” of those opposed to the change, wondering why these people had not spoken up about the racism at her school or a suicide there or reports of sexual assault. Some of the opponents, who apparently had not been fully muted, began to speak over her, questioning the relevance of her comments to the proposal.

At this point, the other board members grew visibly angry—one seemed to be in tears. They not only demanded that the moderator mute the offenders but also that he kick them out of the meeting entirely. The moderator asked, “Did we catch names?” and the board members began to call out names of people who had interrupted. One board member said, “Yeah, I’m listening to a lot of racist people.” No racial slurs or insults were audible on the recording, but another board member noted, “This was not a good day for San Francisco,” referring to the interruptions as “disgusting” and a source of “ugliness.” Another noted that “when we talk about meritocracy . . . these are racist systems,” and she decried the “Trumpian language” of the proposal’s opponents, noting that tests like this one and the SATs “began as ways to justify racism.”

One white parent of an 8th grader told me in a phone interview that his son had been planning to apply to Lowell this year but no longer sees the point, given the new admissions policy. Lowell is one of the only schools in the city that this father thinks could give his son a real education. The man declined to be named in this article because his son was applying to private schools and he worried that the boy’s chances of admission there would be diminished if he were among the parents labeled “racist” for supporting merit-based admissions. A self-described progressive, this father says that he has been “shocked” at just how disconnected the board is from the people they represent. “I can’t deny their reality, but it’s so far from the reality I’m living in, it’s laughable,” he said.

San Francisco already has one of the nation’s largest percentages (55 percent) of students attending private schools. New York, by contrast, has only 20 percent. The change in Lowell’s admissions policy is likely to make more middle-class families either flee to the suburbs or send their children to private schools, especially since the board’s desire to remake the admissions system shows no signs of abating. At the October 2020 school-board meeting, the vice president of the board ended the discussion by saying that “if there’s a way to extend this [new admissions system] past this year, to end this illegal process, I will support that.” All but one of the other members made it clear that they agreed.

Boston’s Exam Schools

Boston School Committee chair Michael Loconto resigned in October 2020 after he was heard on a hot microphone mocking the Asian names of some of the speakers during a meeting about a plan to transform exam-school admissions. But that was not enough to derail the proposal.

The city’s three exam schools—Boston Latin School, Boston Latin Academy, and the O’Bryant School for Mathematics and Science—had required applicants to submit test scores and grades. For admission in fall 2021, the board has adopted a policy whereby the top 20 percent of admitted students will be chosen solely on their grades, with students across the city competing for the spots. The remaining 80 percent will be selected on the basis of grades and by zip code, with students from the lowest-income zip codes given preference. In 2019, Superintendent Brenda Cassellius replaced the Independent School Entrance Examination, a test also used by private schools, with the MAP, or Measure of Academic Progress. The objection to the ISEE was that it included questions about material not covered in typical public-school curricula, and research indicates that the exam puts Black students at a disadvantage. But what began as a move to replace one admissions test with another became a plan to eliminate the entrance exam for the 2021–22 admissions cycle because of Covid-19.

Boston schools did not return to in-person learning in fall 2020, so the administration of the test presented a challenge, though other tests such as the SATs were offered in Boston Public School buildings. But then, as with Lowell, many parents asked why the school couldn’t simply use grades that were available. Why the new zip code approach?

Boston too, it seems, is using Covid as an opportunity to solve what its leadership sees as a race problem. The problem is not new. In 1974, as part of the city’s busing plan, Judge W. Arthur Garrity required exam schools to reserve 35 percent of their seats for underrepresented minorities. But a quarter century later, the First Circuit Court of Appeals struck down these explicit racial set-asides. The percentage of Black and Hispanic students at the city’s exam schools fell to about 16 percent from about 30 percent. And the number at Boston Latin School—the most prestigious of the three magnet schools—is closer to 8 percent.

Racial tensions have continued to present a problem as well. The Boston Public Schools’ Office of Equity found that between November 2014 and January 2016 there were seven race-related incidents at Boston Latin School, most of which were related to social media postings by students. The office said that the school’s internal policy was violated in one of those incidents. In 2016, the U.S. Attorney’s Office launched an investigation and found the school to be in violation of the 1964 Civil Rights Act for failing to properly investigate the allegation of a threat by a white male student to lynch a Black female student, among other incidents. The school’s headmaster and assistant headmaster resigned.

Under this year’s admissions plan for the magnet schools, each zip code would be assigned a certain number of seats based on the average household income in the zip code and the number of school-age children who live there. Supporters believe that what they see as the more-equitable distribution of seats across the city will help the underserved communities and also make Black and Hispanic students feel more comfortable at the exam schools. The Boston Globe noted in reference to Loconto’s ethnic slur at the school-board meeting: “It was an awkward moment for members. . . . Nearly seven hours into the Oct. 21 meeting, exhausted members seemed to struggle to comprehend how a political leader who was on the verge of shepherding through a historic change that would provide Black and Latino applicants with greater access to the exam schools could at the same time disrespect another community of color.”

Critics of the new program, such as Darragh Murphy, a longtime Dorchester resident who attended Boston Latin School in the 1980s, don’t have trouble comprehending this at all. Murphy, who is white, said she believes that the school board decided on the result they wanted “and then worked backward.” The point here, she and others hold, was to reduce the percentage of Asians at Boston Latin School. Chinatown, for instance, has a high average income, driven up by the presence of some luxury apartments, but the families applying to exam schools from this area are not wealthy. Chinatown is projected by the school district to lose exam school seats under the changes.

Fania Feghali and her husband are first-generation Lebanese immigrants who live in West Roxbury, a neighborhood of the city that is projected to lose exam-school seats under the new system. Feghali is an auditor, and her husband is a diesel mechanic. She studied the website Greatschools.com before choosing a place to live and says the most important thing to her was “preparedness for college.” The cheapest private high school near her charges $23,000 annually. The Feghalis currently have two children in a local Catholic school (which they struggle to afford at $7,000 annually) but will consider moving from the city if their 6th grader cannot get into Boston Latin School. “My responsibility as a parent is to offer my kids the best education I can,” Feghali told me.

Like many other parents, Feghali does not understand why the exam couldn’t have been offered despite Covid. Her own children have been going to school in person every day since September, and there were no positive cases at the school in the fall. Why was offering a socially distanced in-person test deemed impossible?

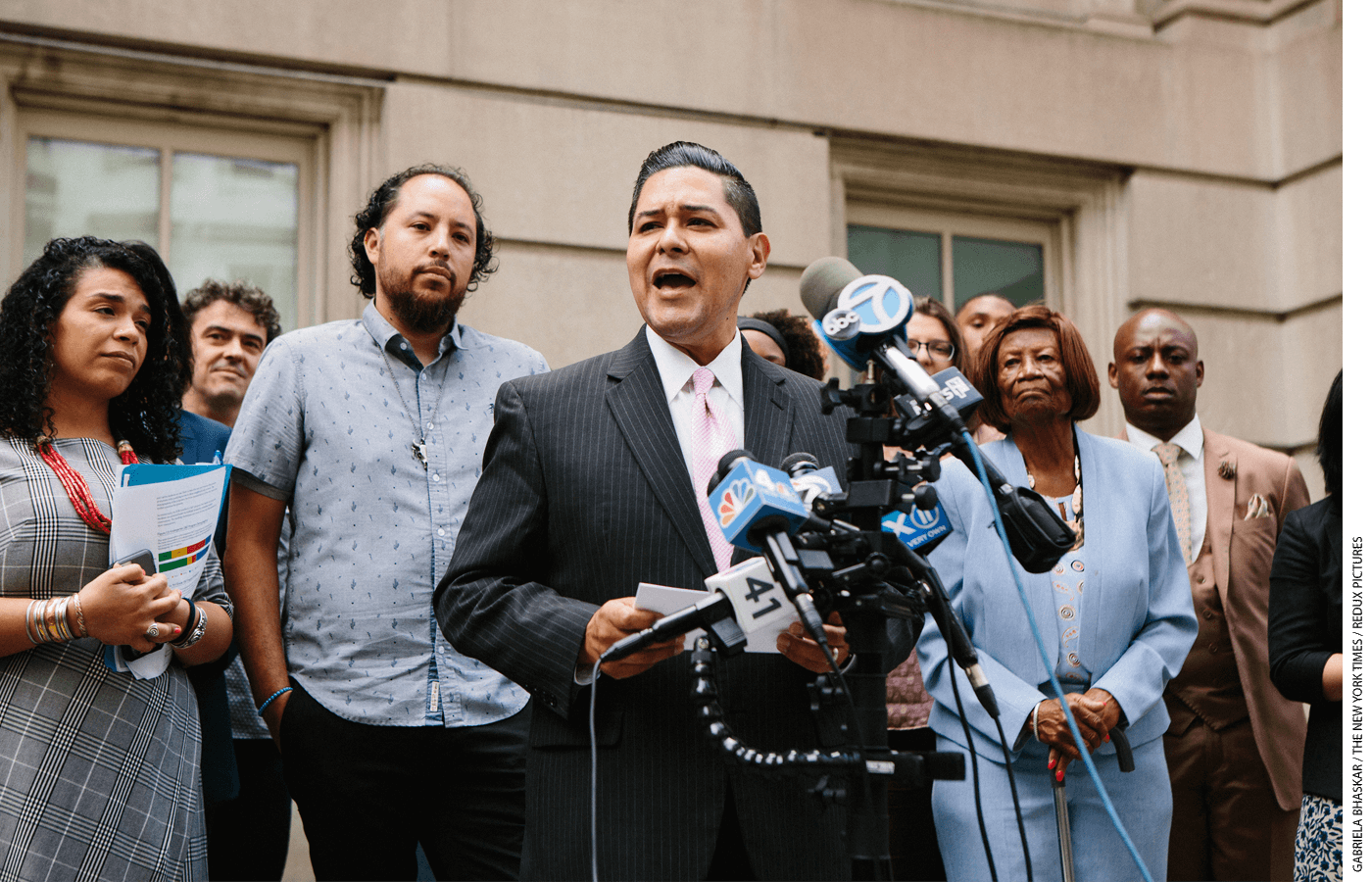

New York City

That is a question eating away at parents all over New York City. With the city’s schools having returned to at least some form of in-person learning for most of fall 2020, the postponement of the Specialized High School Admissions Test (the test required for admissions to three exam schools and various other screened schools) makes even less sense in the Big Apple than it does in San Francisco or Boston. Mayor Bill de Blasio and Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza have expressed their outrage over the small number of Black and Hispanic students admitted to Stuyvesant, Brooklyn Tech, and Bronx Science. In 2019, for instance, Stuyvesant offered admittance to 895 students. Only seven of them were Black, down from 10 the year before. When the topic of schools came up at a recent mayoral press conference, a reporter noted that de Blasio campaigned on “a tale of two cities” and asked the mayor which one Asians belonged to. De Blasio replied, “The specialized high schools still don’t make sense.”

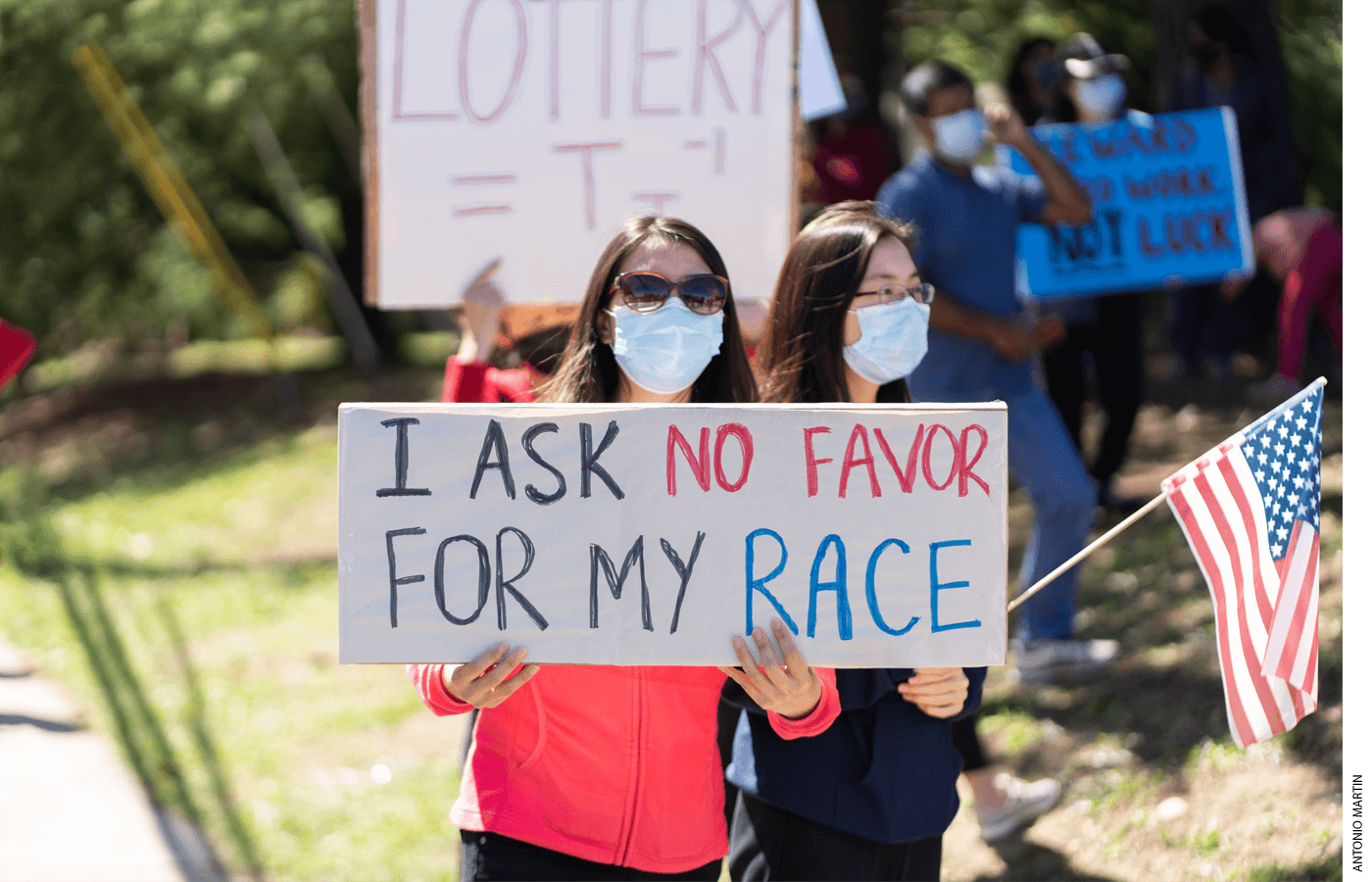

It is worth asking, though, why the schools are not seen as equitable to begin with. Wai Wah Chin, who has had four children graduate from Stuyvesant and is the president of the Chinese American Citizens Alliance Greater New York, notes that “when you have kids chosen only by merit, that’s fair. If you start jiggering, all sorts of abuses happen.” She asserts that with a strictly exam-based system, no one knows “whether parents are rich or poor or whether a kid is tall or fat. The only question is: Can you do the work?”

While some outsiders may assume that the fact that the big three exam schools in New York are majority Asian means that they are catering to a wealthier population, this is far from true. More than half of the students at these schools qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. (While New York City offers free breakfast and lunch to all students regardless of income, officials use Medicaid data to determine which students would qualify by income so the city can receive reimbursement from the federal government.) Many of them are the children of recent immigrants. Unlike middle- and upper-class New Yorkers, they don’t have resources for high-cost tutoring. But, as Chin notes, you can get practice tests out of the local public library.

Questioning Admissions Tests

Some observers wonder whether it makes sense for public high schools to require admissions tests at all. Why shouldn’t schools funded by tax dollars be open to anyone residing in the jurisdiction? If charter schools can help even students from the most difficult circumstances succeed without screening applicants, why can’t other public schools? Though an exam-based process may seem evenhanded, that’s not so when schools fail entirely to prepare broad swaths of the student population in the years leading up to high school. The racial disparities in exam-school enrollment, these critics say, just make the inequities among these students all the more glaring.

For one thing, the older students get, the harder it is to make up for these educational deficits. Perhaps that’s why no one seems to object that public universities don’t accept every state resident who applies. And it’s why almost no elementary schools require admissions tests—though some of them offer gifted and talented programs that may have academic criteria for participation. What’s more, the most successful charter schools require a strong degree of parental support and commitment that mirrors that of the low-income parents who manage to get their children into the exam schools.

Prior to the Covid crisis, de Blasio’s hands were tied. In 1971, the state legislature in Albany mandated that admission to the big three and five smaller schools be based on an exam, thereby heading off an attempt by New York City leaders to shelve the test. And state leaders so far have shown little signs of movement. Last year, the mayor pushed an alternative plan that would offer admission to the top 7 percent of students at each middle school. An analysis by the state budget office concluded that under de Blasio’s plan, “About 19 percent of admissions offers would have gone to Black students, compared with the less than 4 percent who actually attended specialized high schools in 2017–2018. Hispanic students would have received about 27 percent of admission offers, compared with the 6 percent of Hispanic 9th graders who attended the schools last year. The number of Asian students receiving admissions offers would have fallen by about half, to just over 31 percent, while offers to white students would have remained relatively flat.”

The mayor’s proposal did not even get a vote. Alumni, led by businessman and philanthropist Ronald Lauder, a Bronx High School of Science graduate, launched a multimillion-dollar campaign opposing the change. Asian groups also pressured lawmakers, who probably didn’t want to risk harming the schools’ international reputation. The big three have produced 14 Nobel Prizewinners among them, more than most countries. On the other hand, the November 2020 election brought Democrats a supermajority in the Assembly and Senate, meaning that they could change the rules, even over the governor’s objections.

In December 2020, the mayor announced other sweeping changes to the system. The city will eliminate all screening for middle schools for at least one year. Formerly, almost half of the city’s middle schools used grades, attendance, and test scores as admissions criteria. At least for now, all middle-school admissions will be determined by lottery. In January, the mayor also announced that the city’s education department would no longer test children entering kindergarten for gifted programs.

The exam-school question became a campaign issue in a state assembly race in Brooklyn, where a Republican challenger accused a Democratic incumbent of wanting to dismantle the schools, a charge the Democrat denied. The Republican lost by the narrowest of margins in a district that has been held by Democrats for 80 years.

Asians are hardly the only supporters of the Specialized High School Admissions Test and the idea that admission to these schools should be based strictly on merit. Barbara Rivera, who came to this country 20 years ago from Hungary and met her husband here, says the real problem is the pipeline from lower-school grades. She remembers that, when her son was entering elementary school, a judge who lived on her street in Borough Park advised her to get her son into a gifted program. She didn’t think he was gifted and dismissed the idea of sending him to a school farther away from home. By the time he was in 3rd grade, though, it became increasingly obvious to her that her son’s school was not very serious. She remembers a teacher marveling that her son “passed a test.”

“Why,” she wondered, “was the bar so low? Because his last name is Rivera?”

Indeed, the key question in so many of these debates over exam schools is whether it makes sense to wait until high school to try to address inequities in public education. Why aren’t more elementary and middle schools successfully preparing students for these exams in the first place? Commenting on Boston’s new admissions policy suspending the entrance exam, Darragh Murphy wrote in the Dorchester Reporter in November 2020, “The real tragedy is that all this disruption imposed on our 6th and 8th grade families and schools by our mayor and city council is designed to hide the real crisis that we have allowed to grow more dire with every passing year—that the mostly Black and Latinx kids in our Boston public elementary schools are being failed by our leaders and administrators.”

Preparing such students to compete for a spot in a specialized high school is not impossible. In 2018, students of color at three middle schools run by the large Success Academy Charter Schools network in New York were three to four times as likely to gain admission to the exam schools as students in the same demographic citywide.

In other words, it is possible for young people in all racial and ethnic groups to achieve academic success and gain admission to competitive exam schools, but for that to happen at scale would require the kind of systemic change in public-school education that politicians and other leaders have not been willing to make, in New York and elsewhere.

The dispute seems to be reaching a boiling point in New York City. While wealthier New Yorkers have been able to flee the city during the pandemic, the middle and working classes of all races have been stuck and increasingly frustrated with remote learning, as well as the confused messages and lack of leadership from the mayor and chancellor. A public opinion poll in October 2020 showed that three times as many New Yorkers want the state to take over the city school system as want the mayor to remain in control. In early December, a coalition of groups who oppose the exam wrote to Governor Andrew M. Cuomo, asking him to lift the testing requirement this year through executive order, but the governor’s unwillingness to change things before does not bode well for the activists’ demands. Another group filed suit against the city, demanding that the mayor and chancellor set a date for the test. Eventually, the mayor announced a January 27 test date for the city’s 8th graders.

The Boston plan could sail through without any state involvement, just as San Francisco’s has. Boston may face more legal scrutiny, though, because its convoluted formula seems designed to achieve a particular racial result. (San Francisco’s, by contrast, simply makes Lowell’s admissions criteria the same as every other school in the city.) As Joshua Thompson of the Pacific Legal Foundation, a nonprofit that has litigated racial discrimination cases, notes, “There are legal methods to challenge policies that have a facially neutral purpose but have a differential effect.” While he says these cases are hard to challenge during Covid, going forward opponents could “try to get at the true purpose of the law. If racial balance is the goal, it should be enjoined.” Given how open these politicians and school leaders have been about wanting more racial balance—and even their blatant bias in some cases—that would seem easy to prove.

Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Fairfax County, Virginia

Earlier this fall, the Pacific Legal Foundation sent a letter to the Fairfax County School Board warning them that their attempt at racial balancing is “patently unconstitutional.” Citing the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, the letter notes that “when examining the outcomes of the merit lottery process, it is impossible to see the changes to the TJ admissions process as anything other than an attempt at racial balancing according to the demographics of Fairfax County.”

A few weeks later, the board altered the plan. It now would reserve 100 slots for the highest-evaluated students based on a holistic review of their applications, including recommendations or a problem-solving essay. The remaining 400 seats would be filled by “merit lottery,” with seats divided evenly among students with a minimum 3.5 GPA in the geographic areas Thomas Jefferson serves. But these changes did nothing to address the legal criticisms made by the Pacific Legal Foundation lawyers.

The battle over Thomas Jefferson—a regional magnet school that consistently ranks at the top of the U.S. News and Newsweek surveys of America’s best high schools and that regularly claims winners of nationwide science competitions—began almost a decade ago with a civil rights lawsuit filed by the NAACP in 2012. The filing asserted that Black and Latino students were being shut out of Thomas Jefferson because Fairfax County consistently fails to identify them for gifted programs during the lower grades. Despite renewed outreach efforts, the district has failed to get more Black and Hispanic students into Thomas Jefferson. Today, the student body is 71 percent Asian, 19.5 percent white, 2.6 percent Latino or Hispanic, 1.7 percent Black, and 4.7 percent students who identify as another ethnicity.

Last year, the school’s racial soul-searching took on a new tone and urgency. In June, the principal sent a note to parents explaining that “the recent events in our nation with Black citizens facing death and continued injustices remind us that we each have a responsibility to our community to speak up and take actions that counter racism and discrimination in our society.” Among the concrete steps she recommended was replacing the school’s mascot, an American Colonial figure, because of “colonialism’s role in our country’s history where certain classes exerted power over others as a means to economically exploit, oppress, and enslave them.” After noting that Thomas Jefferson’s racial makeup does not mirror the community’s, she asked, “Do the TJ admissions outcomes affirm that we believe TJ is accessible to all talented STEM-focused students regardless of race or personal circumstance?”

Many parents objected to the changes in the admissions process, and the debate has become bitter. Suparna Dutta, the parent of a sophomore at Thomas Jefferson, worries that plans for racial rebalancing run the risk of making this country more like her native India. The quota system instituted for education and employment there to make up for the caste system of old, she says, has “led to a lot of brain drain. People flee for better opportunities.” Now, she says, “I’m afraid my adopted country is going down this road.”

What is particularly curious about the proposal to eliminate Thomas Jefferson’s exam and simply admit students by lottery is that the school’s white population is projected to more than double under the new criteria, going from 18 percent of Thomas Jefferson students to as high as 48 percent—figures that were calculated by a parent group called the Coalition for TJ. Even if Fairfax County accomplished all of the outreach to Black and Hispanic families that the district promises—something it has failed to do in the past—the end result of the district’s attempt to achieve racial balance would be the presence of many more white children at Thomas Jefferson.

The potential increase in white students at Thomas Jefferson is just one of many unintended consequences that could arise from the admissions-policy changes in San Francisco, Virginia, New York, and Boston. It seems likely that these urban areas will lose a significant number of families to private schools or to the suburbs. Some of the policy changes may prove to be temporary, but with cities seeing higher rates of crime and homelessness and so many professional jobs going remote, many families may see the shifting admissions practices at these schools as the final straw.

Like the school boards in San Francisco and Boston, the Fairfax County board has become the subject of public ire this year and seems increasingly disconnected from the families it is supposed to serve. Schools there did not reopen in the fall of 2020. A recent study found that remote learning resulted in an increase of 83 percent in students who are failing two or more classes. The district came under heavy criticism in fall 2020 after paying the anti-racism activist and scholar Ibram X. Kendi $20,000 for a one-hour presentation to school leaders. The district sent out a memo discouraging parents from forming educational pods for their children because “they may widen the gap in educational access and equity for all students.” Meanwhile, the superintendent himself has enrolled his own child in private school. The district’s parents seem more interested in the failures going on in their children’s (virtual) classrooms than any of the racial drama on offer.

Perhaps realizing that the lawsuits over racial bias seem rarely to provide clear answers and also can take years to wind their way through the court system, the opponents of this change at Thomas Jefferson have tried a new tactic. In November 2020, they filed a lawsuit arguing that the proposed change in admissions requirements goes against the Virginia law establishing and regulating Governor’s Schools—of which Thomas Jefferson is one—meant to serve gifted students. That law specifically requires that Governor’s Schools include a “nationally norm-referenced aptitude test” as part of the process for identifying children with particular academic aptitudes. The plaintiffs argue that “under the No-Testing Decision, the Thomas Jefferson Governor’s School will no longer be a high school devoted to the education of gifted students.”

The Indian-born author Asra Nomani, whose son is a student at Thomas Jefferson, said that demanding that the school district serve gifted children—just as they serve other kinds of learners—will prove more effective than a racial-bias argument. “Kids that are advanced learners have faster processing skills. They’re the ones firing questions at teachers and yet do not have great social skills,” Nomani said. These may be generalizations, but there is certainly a case to be made that school districts serve students with such varying levels of skills and aptitudes that a one-size-fits-all approach is not going to meet anyone’s needs well.

One thing that’s clear is that schools for gifted students are oversubscribed. When Michael Bloomberg was mayor of New York, for instance, he expanded the number of screened schools—but even that did not meet the demand.

It is possible that some of these urban parents are not even looking for “gifted education,” but simply a decent education for their children. Many parents of academically motivated students are not worried about science competitions and just want their children to learn in the company of other strivers. Even though there is some evidence that the schools themselves do not make an enormous difference in the future prospects of their students—at least when it comes to college enrollment, college graduation, or college quality—parents may want their children to be in an environment with peers who have similar interests.

Though many politicians, school-board members, and activists may see the Covid crisis as an opportunity to change longstanding admissions policies they view as faulty, the pandemic also seems to be a kind of double-edged sword for education policy. The switch to remote learning and the failures of public education to deliver even basic instruction during this crisis have forced a laser focus on school and district leadership by parents nationwide. Middle-class parents who were previously able to find ways for their children to get a decent education have found themselves frustrated and angry at local politicians and school administrators for running roughshod over the interests of their children. And plans for radically altering some of the only schools that seem to be working are not going over well.

Naomi Schaefer Riley is a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a senior fellow at the Independent Women’s Forum.

The post Exam-School Admissions Come Under Pressure amid Pandemic appeared first on Education Next.

[NDN/ccn/comedia Links]

News…. browse around here

No comments:

Post a Comment