School districts are meant to function with the needs of children and the community in mind. Most are governed by nonpartisan school boards who rely on an expert professional—a superintendent—to help them make sound educational decisions. With this structure, they should, in theory, be able to respond to local conditions and do what is best for the health, safety, and education of the community.

Has this occurred in the pandemic era? In a new study, we find clear and convincing evidence that this is not the case. We find that the responses of school districts to the Covid-19 pandemic hinged mostly on political factors other than public health. Our analysis evaluated how nearly 10,000 school districts approached re-opening decisions this fall—specifically whether they chose to start the year with hybrid, remote, or in-person classes. It reveals that political partisanship, union strength, and competition from Catholic schools heavily influenced district decision-making.

We first sought to determine whether the overall severity of the pandemic in a local community best explained the initial approach taken by districts to re-opening. If school board decision-making was—as has historically been the case—mostly sensitive to the particular needs and conditions of the local community, we would expect that in districts where the pandemic was well-managed and new Covid-19 case rates remained relatively low, schools would have been more likely to resume traditional in-person learning. Similarly, school districts in communities where case rates remained stubbornly high and public health conditions poor would have been more likely to take a cautious approach, relying on fully remote instruction to start the year.

But this is not what we find.

Instead, our analysis reveals that the percentage of the vote won by Donald Trump in a school district’s parent county in 2016 strongly predicts whether schools re-opened with in-person instruction or chose to educate students remotely. What’s more, the severity of the public health crisis itself—measured with a variety of per capita and cumulative metrics related to the spread of Covid in the county—had little or no effect on school districts’ re-opening choices.

However, partisanship is not the only factor strongly related to how school districts elected to reopen this fall. We find that areas with stronger teachers unions were, all else equal, less likely to resume fully in-person learning. We measure this using district size, since some studies have found size to be related to teachers union strength. But size is a noisy measure that could be capturing many different factors. Because of this, we also examine whether districts that bargain collectively were more likely to put in-person learning on hold this fall. Unfortunately, we only have detailed information on collective bargaining status for a subsample (1,500) of our larger sample of districts. Nevertheless, irrespective of the measure of union strength used, we find that school districts with stronger teachers unions were more likely to remain fully remote than districts with weaker ones. Notably, this finding is in line with the work of other scholars and appears to be robust to different indicators for assessing union strength.

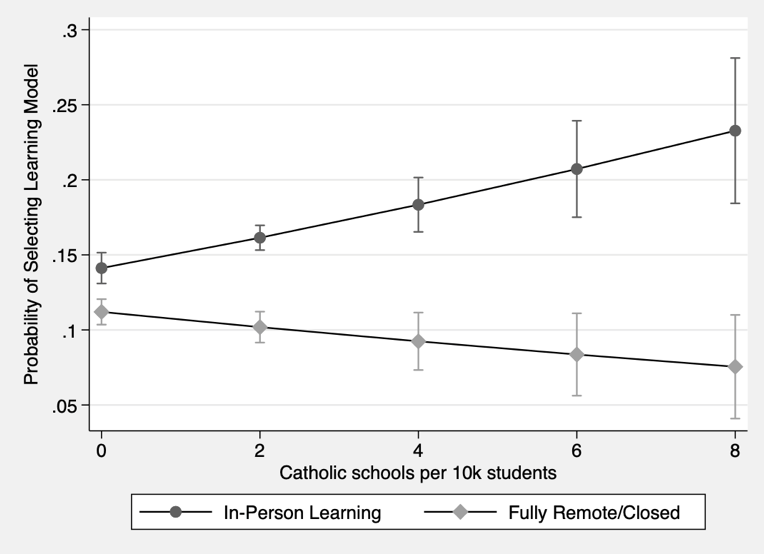

Finally, we find evidence that the number of local Catholic schools was positively associated with school districts offering in-person learning rather than remote-only instruction. Where there were more Catholic schools for every 10,000 students, school districts were more likely to open in-person and less likely to open remotely, as shown in the figure below. This suggests that public school districts may be responding to competitive pressures, as some parents pull their kids out of public school systems to attend in-person private schools. Indeed, enrollment in Catholic schools has been surging in some areas. Figure 1, below, shows this visually by presenting the marginal effects of increased exposure to Catholic schools (per 10,000 students) and the likelihood that a district opted for remote or in-person instruction, holding all other factors, including coronavirus case rates, constant.

Our empirical analysis takes into account state-level factors—like pandemic response policies—that might impact school openings, as well as a host of other factors, like the area’s urbanicity, racial composition, and district affluence.

What should we make of these findings? The impact of local political and market forces like union strength and private school competition are not necessarily out of line with conventional accounts about the political economy of local school districts. Scholars have long found teachers’ unions to be influential players in local school politics, and it makes sense that a labor union would fight for the safety of its members. As to the effect of Catholic schools, there have been several studies documenting the effect of competition on public schools. Competition may be more intense during the pandemic, because the threat of parents exiting the public school system likely is greater due to the challenges posed by remote learning.

Our most noteworthy finding is that local education decisions about something as basic as when and how to re-open schools for learning are becoming strongly polarized along partisan lines just like every other policy area, where local politics have increasingly been nationalized. It remains to be seen whether this is a short-term Trump-specific effect or a more general hardening of partisan attitudes that will shape school board politics for years to come.

One would think that, because nonpartisan local school district governments remain much more institutionally insulated from partisan and nationalizing influences, they should (in theory) be freer to make policy decisions based on the best scientific evidence and public health concerns and keep such decisions divorced from things like attitudes toward the president and basic partisanship. We do not find any strong and consistent evidence of a relationship between public health conditions on the ground and school district policymaking. We do find a clear and substantial connection between partisan tribalism and district re-opening plans. That upends much conventional wisdom about the role of national partisanship in local school policy in the United States.

Leslie K. Finger is assistant professor of political science at the University of North Texas. Michael Hartney is assistant professor of political science at Boston College.

The post Remote or In-Person Reopening Decisions Are Linked to Trump 2016 Vote Share, Catholic School Presence, a New Study Finds appeared first on Education Next.

No comments:

Post a Comment