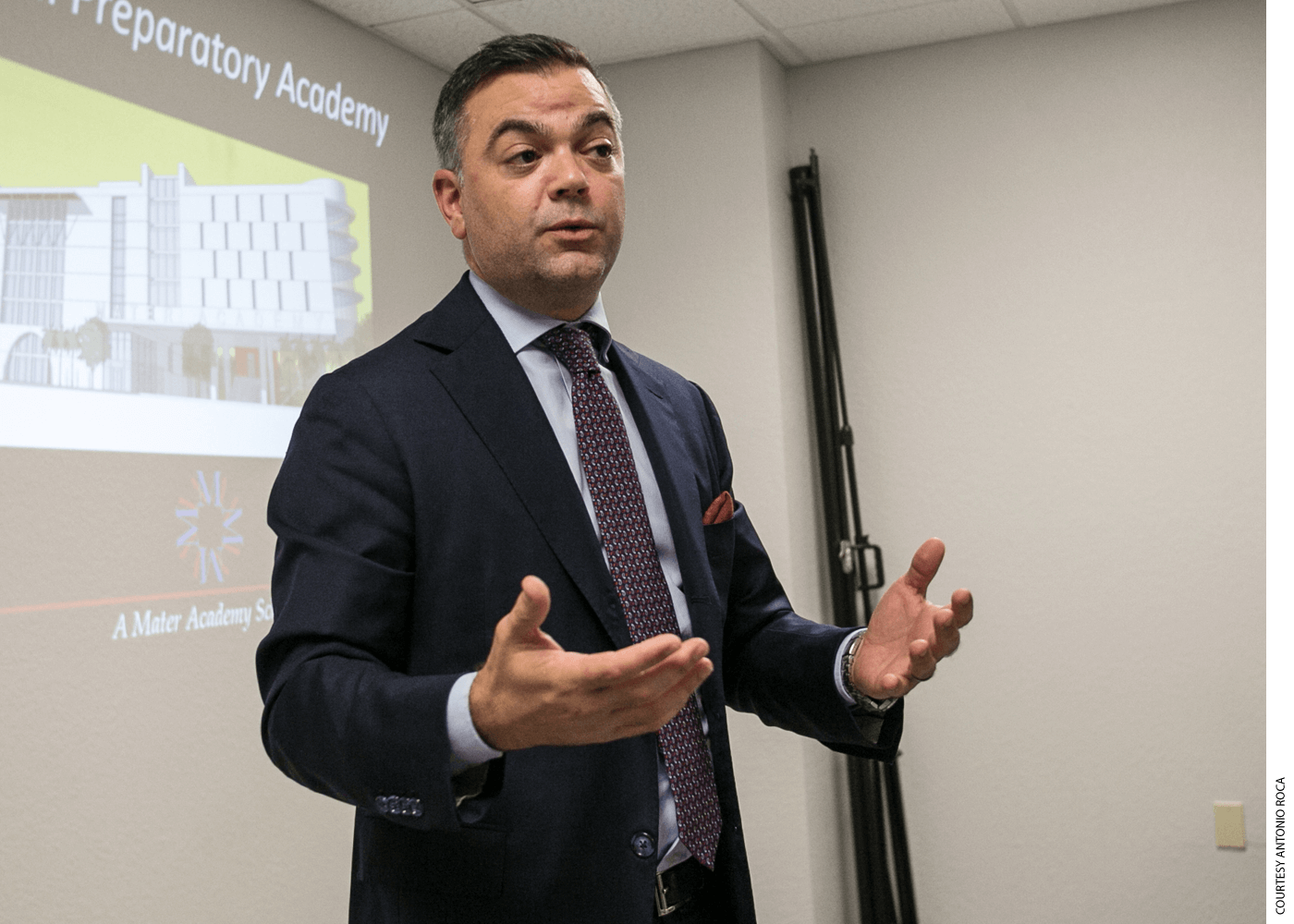

In mid-February 2020, Antonio Roca’s team at the education-management company Academica started to get some disturbing reports from the firm’s Milan branch. It appeared that the virus ravaging Wuhan, China, had made its way to Northern Italy. This menace wasn’t going to stay contained for long. Could it make it to the States? The team should probably prepare.

In mid-February 2020, Antonio Roca’s team at the education-management company Academica started to get some disturbing reports from the firm’s Milan branch. It appeared that the virus ravaging Wuhan, China, had made its way to Northern Italy. This menace wasn’t going to stay contained for long. Could it make it to the States? The team should probably prepare.

Roca is the managing director for the virtual education division of Academica, a large U.S.-based education service provider. The company manages 200 brick-and-mortar charter schools in 11 states, serving some 125,000 students. Via online instruction, it serves an additional 20,000 students in 11 countries, including Italy. It is one of the for-profit charter-school companies that left-leaning education activists have set their sights on.

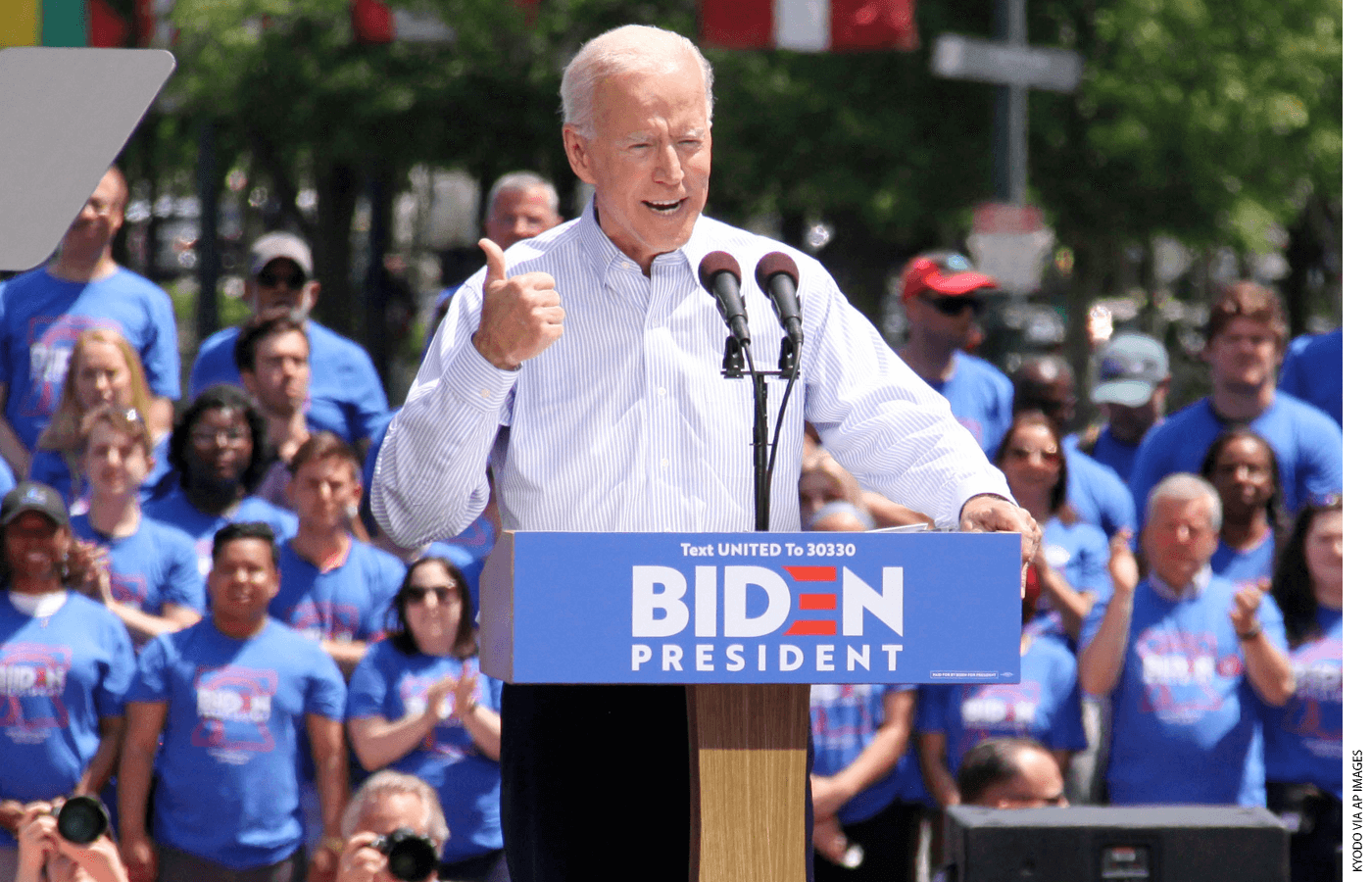

The 2020 Democratic Party platform promises a ban on all federal funding for for-profit charter schools, explaining that “education is a public good and should not be saddled with a private profit motive.” In May 2020, more than 200 activists, including Diane Ravitch, Jonathan Kozol, Danny Glover, and Michael Moore, signed an open letter to presidential candidate Joe Biden calling for an outright prohibition on such schools.

A look at Academica’s response to the Covid-19 crisis might temper some of that distrust.

In early March, the company surveyed parents of its on-campus students, hoping to identify potential problems with student Internet access and hurdles that the firm would need to overcome to move instruction online. Staff developed both hard-copy and digital resources (in English, Spanish, and French) and distributed thousands of devices to students on campus before schools had to close.

On Friday, March 13, the first group of Academica schools closed in South Florida. The company trained 5,000 teachers via videoconferencing. The videoconferencing tools had already been vetted for security via the firm’s Colegia platform, a central hub of educational applications, content, and communications that Academica had created to ensure continuity of live instruction. Luckily, many of its schools were slated to be on spring break the following week, buying the staff time to train the rest of the teachers.

On Monday, March 16, the first tranche of Academica schools reopened online, with the rest reopening as they came back from spring break. For the remainder of the school year, Academica offered at least four hours of remote live instruction per day. Students reported online at the usual school start time, wearing their school uniforms. Academica created professional-learning communities for teachers to work together to navigate the obstacles that emerged during the pandemic. It developed online tools that offered confidential meeting rooms for pullout services and direct instruction for students with special needs. It continuously surveyed parents and tracked attendance every day. In late April, the company was seeing 94 percent attendance, a better rate than in its traditional brick-and-mortar schools.

When the Center on Reinventing Public Education tracked a set of 82 public school districts last spring, it found that 27 of them—one third—did “not set consistent expectations for teachers to provide meaningful remote instruction” during the closures, and 13 of the 27 did “not require teachers to give feedback on student work.” Meanwhile, Academica was kicking into overdrive.

Why?

“We’re sensitive to our customers,” Roca said. “If we don’t respond, they’ll talk with their feet.”

When Is a School a For-Profit?

According to data from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, approximately 13 percent of the nation’s more than 7,000 charter schools are operated by for-profit education management organizations or education service providers. About twice that number of schools are run by nonprofit charter management organizations, and five times as many are freestanding charters that operate independently. Over the past decade, the number of schools operated by nonprofit organizations has grown more than twice as much as the number operated by for-profit organizations (see Figure 1).

But is a school managed by a for-profit organization a for-profit school?

“Most people don’t understand what ‘for-profit’ means” in the context of charter schools, said Brian Britton, CEO of the for-profit education management organization National Heritage Academies. “We are partnering with nonprofit school boards.”

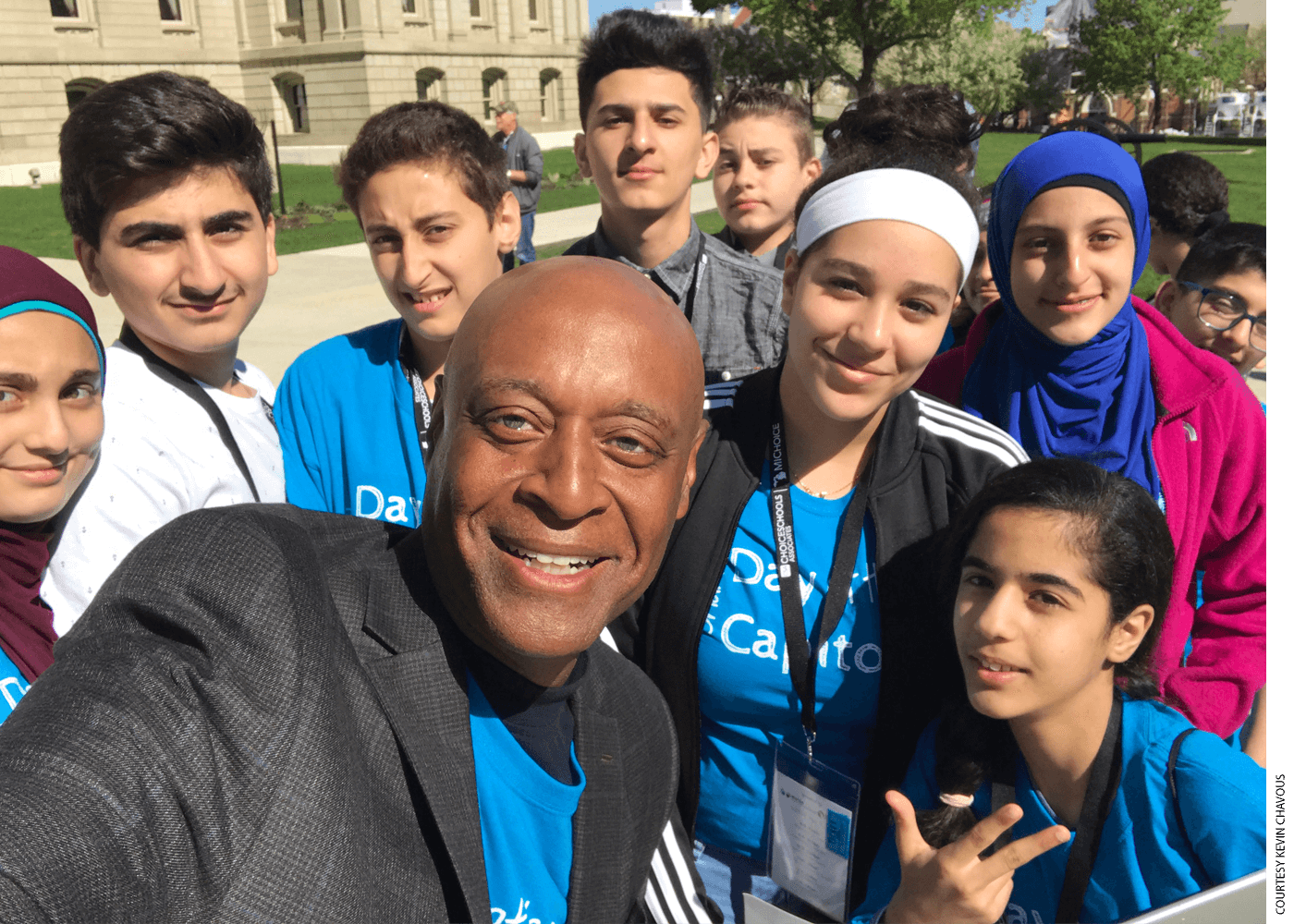

Kevin Chavous, president of academics, policy, and schools for K12 Inc., agrees. “We don’t actually hold any charters,” he said. Chavous likens K12, a for-profit that provides online schooling and curricula, to other companies with which schools typically do business, asserting, “schools have vendors for curriculum or roof repair. We are a vendor.”

Roca of Academica puts it this way: “Although Academica itself is a for-profit company, the CMO networks and schools who hire Academica are nonprofit entities. Together, we are referred to as hybrid organizations.”

In every state except Arizona (and, until recently, California), for-profit charter operators are not allowed to receive government funding or hold a school’s charter. However, nonprofit charter boards can choose to contract with a for-profit management organization instead of contracting with a nonprofit operator or hiring a traditional management team to run the school.

Rudyard Ceres, a board member of Brooklyn Excelsior Charter School, described one benefit of partnering with National Heritage Academies: “As a result of NHA’s scale, they are able to spot patterns and see what is working across a wide range of schools,” he said, “which helps us to troubleshoot in real time. Further, the model allows us to rely on NHA’s business expertise, which permits our educators and staff to focus on what matters most: helping our students reach their fullest potential.”

Charter boards can, and do, fire their management organizations and contract with new ones. Last year, for instance, Indianapolis Public Schools chose to end its contract with Charter Schools USA, which had been managing three of the district’s charter schools since 2011. The district has chosen a nonprofit charter management organization, Christel House International, to operate one of the schools and is considering whether to manage the other two schools itself or contract with another management organization.

Schools of all types contract with vendors. They use for-profit companies to provide food services or perform maintenance on the building. They hire security guards and buy textbooks from for-profit publishers. They contract for professional development and office supplies. For-profit companies provide back-office support and run learning-management systems. They provide assessments and data analytics. The list goes on.

Some schools contract with vendors to manage and operate their schools. It is these, and only these, that are described as “for-profit” schools. But why draw the line at school management and operation?

Conversely, why would a nonprofit charter school that has its own management team but contracts out its curriculum and textbooks, its learning-management system, its food services, its back-office accounting and human resources, and its substitute teachers be considered nonprofit?

Examine the vendor contracts of traditional public school districts, and you will see lines blurring there as well.

Maybe the contrast drawn between for-profit education mangement organizations and non-profit charter management organizations is a distinction without a difference.

Transparency, Scale, and Skin in the Game

Debates about the role of for-profit operators go back decades. The first issue of this journal, in 2001, featured a forum with contributors John Chubb, then of the for-profit Edison Schools, and Henry Levin of Teachers College headlined “The Profit Motive: Will it benefit kids?”

At the time, private businesses had only recently begun running public schools. Increasingly, as Chubb wrote, commercial firms were “seeking to actively manage entire public schools—hiring and firing; supervision, evaluation, and compensation; professional development; curriculum, instruction, and assessment; educational technology; plant management—everything.”

To many people, the idea was anathema. The mission of schools, after all, was educating the young, not making a buck. Chubb’s essay, though, laid out arguments in favor of the concept. First, private companies, in contrast to the nation’s patchwork of (at that time) 15,000 school districts, could consolidate administrative functions to serve multiple schools and employ economies of scale to drive down the prices of goods and services. Second, the capital-raising ability of for-profit companies, along with the profit motive itself, could spur greater investment in research and development.

And finally, because private companies would not be hampered by collective bargaining agreements or bureaucratic red tape, they had the potential to create more nimble organizations that could better meet the needs of students.

Henry Levin countered by describing the potential hazards of for-profit school management and operation. He doubted that businesses could compete profitably with government-subsidized public schools and nonprofit private schools. Most privates, he pointed out, set tuition levels below their costs and supplemented tuition dollars with vigorous fundraising.

Furthermore, the for-profit sector had yet to innovate significantly or distinguish its approaches from those of traditional schools. Although for-profit companies were experimenting with larger class sizes, using more junior teachers or contract employees, and starting to introduce technology, their schools looked largely the same as public and nonprofit schools.

Levin also warned of malign effects that could develop from the profit motive and companies’ efforts to attract “clients.” For-profit schools might be tempted to focus narrowly on maximizing test scores, a goal that could lead to pernicious practices such as recruiting only students likely to perform well on tests, narrowing the curriculum, and selecting, rewarding, and punishing teachers based mainly on their ability to improve test scores.

Over the years, the key points in this debate have changed little. When I asked leaders in the for-profit realm to name the advantages of their structure, these familiar themes returned.

Brian Britton of National Heritage Academies asserted that his company’s for-profit status allows it to scale up much more efficiently than a nonprofit organization could.

The primary reason? “We don’t have to fundraise,” Britton said.

Consider two charter operators, one for-profit and one nonprofit, both of which want to start a new school. Leaders at the nonprofit will have to raise philanthropic capital, up to millions of dollars, and have the capacity to continue raising money until enough state funding comes their way through student enrollment. Whether the founders acquire and renovate an existing building or purchase land and construct a new one, developing a school facility will be a major undertaking that eats up time and energy.

Businesses, by contrast, can borrow money more easily and can deploy capital faster. Britton says that without the capital he was able to access, he wouldn’t have been able to renovate and expand the former Catholic school on the East Side of Detroit that now houses the Detroit Enterprise Academy. According to data from the state of Michigan, that school now has higher rates of student proficiency than schools with similar student characteristics, faster rates of student growth, better teacher retention, and fewer mid-year transfers, all with lower staff-to-student ratios than comparable schools. It would appear that, because National Heritage Academies had access to capital, 739 K–8 students in Detroit have access to a better education.

Beyond the ability to grow more nimbly, for-profits can deploy further advantages. Private businesses can leverage economies of scale in ways that most nonprofits can’t. As Kevin Chavous of K12 puts it, with anything from shipping computers to designing and deploying curriculum, “we are able to create value-add services at a much better price point than if people had to put them together themselves.” This agglomeration effect can help schools operate much more efficiently.

For-profit management companies also face a higher level of accountability than traditional public and nonprofit schools generally do. Both Britton and Chavous argued that their operations were more transparent and more accountable than nonprofit operators.

“There is no transparency like in a for-profit, publicly traded company,” Chavous said. He would know. He served as a member of the Washington, D.C., city council for more than a decade, and also as a nonprofit leader, before entering the for-profit sector.

Private companies have the additional accountability that comes with having skin in the game. As Britton puts it, National Heritage Academies has an “extra dose of heightened accountability” because “the pressure of operating as a for-profit imposes a significant amount of discipline.” If a school fails, it loses money, and investors punish it.

“If we run great schools, that is major shareholder value,” Chavous said. “If people feel we run bad schools, that is bad for business.”

Leaders at K12 have had firsthand experience with this principle. In early September 2013, the company’s stock price was near its all-time high, at over $36 per share. But on September 17, investor and education-reform advocate Whitney Tilson presented a 110-slide PowerPoint presentation to the Value Investing Congress in New York City, detailing what he saw as the educational shortcomings of K12 and making his case for shorting the stock. He argued that “K12’s aggressive student recruitment has led to dismal academic results by students and sky-high dropout rates, in some cases more than 50 percent annually.” By the end of October, the stock’s price had fallen to half where it was before Tilson’s presentation. It would drop further, though less dramatically, until January 2016, when it bottomed out at just over $8 per share. Over the next three years, the stock climbed back up to its “pre-Tilson” price, only to fall again to about half of its peak.

K12 is not the only for-profit entity the market has disciplined. For years, Edison Schools (now EdisonLearning) was synonymous with for-profit education. Founded in 1992, it grew to manage 136 schools in 23 states. Founder Chris Whittle argued that his company could run schools for less money than public school districts did, and with better results. It couldn’t, and the market punished the firm. While the stock price rose to $36 per share in early 2001, by late 2002, it was trading at 14 cents. It was eventually sold and taken private in November 2003 at a share price of $1.76. It has since moved away from trying to manage schools to providing supplemental services like a more traditional school vendor.

The market’s harsh discipline affects the decisions that these enterprises undertake. School leaders have learned that unsustainable growth is poison for share value. So, when it comes to opening new schools or scaling up operations, the likelihood of success plays a huge role in the decision-making process. As Britton of National Heritage Academies puts it, “We don’t want to grow unless we can deliver what we’ve promised.”

Twenty years into the for-profit experiment, it is clear that skeptics were right to express concern about some of the recruiting and management practices that for-profit operators might adopt. Clearly, some of them did try to expand too quickly, and others engaged in practices that, while cutting costs, did not lead to higher student achievement. Yet these behaviors were not allowed to run amok—they were punished by the feedback loop of consumer sentiment and stock price. When schools behaved in ways that were detrimental to children and families, researchers and gadflies made this known, and investors took note.

Today, leaders of for-profit education management companies stress that they have learned from their predecessors and don’t want to repeat mistakes.

One hazard that critics of for-profits warned about did pose problems—but in traditional public schools and nonprofit charter schools. Accountability in the form of hiring, rewarding, and punishing teachers based on their ability to affect student test scores became a major policy initiative. Education advocates and parents often accused schools of narrowing the curriculum and “teaching to the test,” and some school districts made headlines for cheating on standardized tests. More informal gaming, whether by focusing on students who were scoring close to proficiency cutoff points on tests, or by moving strong teachers from non-tested to tested grades, would emerge in the subsequent years. The profit motive, as traditionally understood, had nothing to do with it.

What the Research Says

Perhaps research can indicate whether the experiment in for-profit education has been helpful or harmful.

In 2017, Stanford’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes released a study of charter management organizations across the country. It included a breakout of data on for-profit and nonprofit charter operators. The study found that students who attended schools managed by a nonprofit charter management organization outperformed demographically matched students in traditional public schools by 0.02 standard deviations in terms of annual growth in both math and reading, a difference that the researchers equate to about 12 additional days of learning. Those who attended for-profit schools scored lower than matched traditional public school students by 0.02 standard deviations in math but outperformed them by 0.01 standard deviations in reading, a finding that did not meet tests of statistical significance.

The Stanford study results on the three education management organizations mentioned in this article were mixed. The researchers found that Academica had a statistically significant positive impact on student reading scores, but no impact in math. K12 showed statistically significant negative impacts in both math and reading. National Heritage Academies showed statistically significant positive impacts in both math and reading.

In 2018, Susan Dynarksi and colleagues from the University of Michigan published a paper with the National Bureau of Economic Research that looked specifically at the performance of National Heritage Academies schools. The researchers compared the test scores of admissions-lottery winners and losers to estimate the charter schools’ effects on student achievement. They found significant positive effects in math, and smaller effects, which were not statistically significant, on other outcomes. They also found that the largest positive results, in contrast to findings in much of the literature on charter schools, were concentrated in wealthier, nonurban areas. The researchers surveyed school administrators at National Heritage Academies to try to tease out what the schools did differently. Administrators cited a number of the organization’s practices as potential differentiators: substantial parental engagement, ability grouping, a “no excuses” philosophy, mentoring of teachers by principals, and teacher bonuses.

In sum, the student-performance differences between for-profit schools and the traditional public schools their students would likely have attended neither convict nor exonerate for-profit management companies. There is a range of performance among providers; on standardized tests, their students perform about the same, on average, as students in the schools they are ostensibly attempting to replace.

Online charter schools, many of which are for-profit, have attracted their share of attention as well. In 2015, a team of researchers from Mathematica Public Policy Research, the Center on Reinventing Public Education, and Stanford published an in-depth examination of online charter schools. The headline finding was substantial negative effects for students in online schools, who lost the equivalent of 72 days of learning in reading and 180 days (a full school year) of learning in math.

One caveat applies to these results, though, and it’s related to the policy environment in which online schools operate. The Mathematica team found through surveys of students attending online schools that “student-driven, independent study” was the dominant mode of learning, with many online charters having high student-teacher ratios and offering limited contact time between students and teachers. The Center on Reinventing Public Education team noted that most state laws did not allow online schools to screen applicants to identify those most likely to thrive in an independent-learning environment (for example, students who are self-motivated and who have significant parental support). What’s more, in most states, school were paid based on enrollment rather than outcomes (for example, course completion).

The Stanford research design matched online students with non-online students to compare them on a set of observable characteristics. Online students, though, may vary from others in important but unobservable ways. For instance, they may be dealing with issues that cause them to need online schooling—issues that don’t show up in their demographic profile but that negatively affect their test scores.

That said, it is far more likely that online schools simply enrolled students who were not a good fit for the model. That is a problem of both regulation and incentives, and it could be addressed by changing the policy environment in which these schools operate.

It appears that, as in many realms of education, the quality of for-profit operators varies widely. Some for-profit schools are innovating and attempting new and different pedagogical strategies that are better meeting the needs of students, and some aren’t. Of course, one could say much the same about nonprofit charter schools and traditional district schools.

Going Forward

The pursuit of profit can lead people to take actions that reap good results for students, but it can also lead to pernicious practices. How can policymakers encourage the former and rein in the latter? They can hold all schools accountable, whether they are for-profit charters, nonprofit charters, or traditional public schools.

Giving parents the opportunity to opt out of schools that are not working for their children and opt in to schools that might do better is the most effective way to keep all of these forces in check. Empowering the people who are the “consumers” of education is the best tool in our toolbox to ensure that they are served well.

This is called a market. And, as for-profit operators have learned, it is a harsh disciplinarian.

But while the stock market in which for-profits operate is a true market, K–12 education in its current form is far from a free market. Prices are fixed. The largest player is the government. Gatekeepers restrict supply. Regulations stack hundreds of pages tall. The fastest-growing sector of alternative school operators is subsidized by tax-advantaged philanthropic giving.

This could help explain why for-profit education management organizations have remained a minor player in the charter-schooling landscape, which is itself a small player in the education system writ large. In 2007, according to data from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, education management organizations managed about 10 percent of all charter schools. By the 2016–17 school year, that share had only increased to 13 percent.

If policymakers want to get the most out of for-profit operators (with the added benefit of getting the most out of government-run and nonprofit schools, too), they will need to support a genuinely competitive market that allows all families to choose learning environments that work best for their children.

Michael Q. McShane is director of national research at EdChoice.

The post Ban For-Profit Charters? appeared first on Education Next.

No comments:

Post a Comment