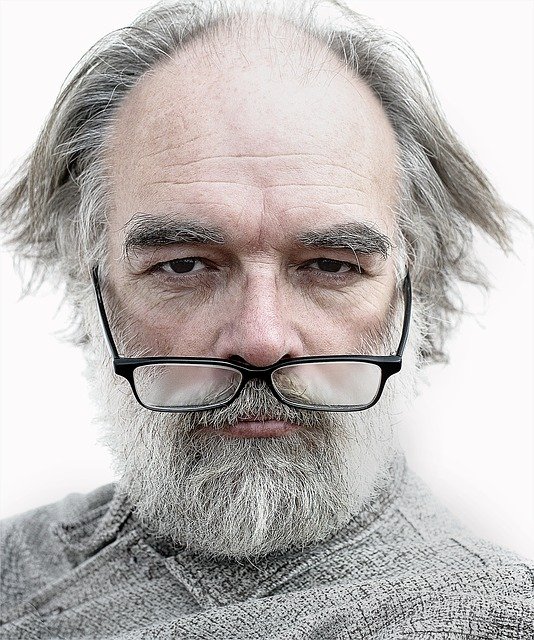

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas

The Supreme Court heard oral argument Monday on two of this term’s most highly anticipated cases: Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru and St. James School v. Biel. Both involve teachers who were fired from Catholic Schools (For background, please see “Justices Will Hear Cases About L.A. Catholic Schools”). The question was whether their firings were covered by the “ministerial exception,” which allows religious institutions to select their own ministers and, thus, exempts ministers from statutory employment protections.

When the Supreme Court first recognized the ministerial exception in 2012’s Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission it held that the First Amendment’s “free exercise” clause must allow must allow religious institutions to hire and fire ministers—otherwise the government could compel them to retain individuals that the institution believes are no longer suited to teach their faith. But it left the scope of the exception broadly undefined. Monday’s argument focused on how far it should go. While the court’s usual ideological divisions were apparent, the balance of oral argument seemed to favor the schools.

On one side, the liberal bloc of justices expressed concern that if these teachers were considered ministers then nurses or janitors in religious hospitals could be fired because they were considered ministers. On the other, the court’s conservatives were more concerned about protecting the rights of religious institutions to determine who should be considered a minister. Justice Gorsuch took perhaps the hardest line, indicating that he felt uncomfortable having a “secular court” second-guessing a religious institution and declaring that some employees’ activities were insufficiently related to religion to count them as ministers.

Perhaps the most interesting question came from the normally taciturn Justice Thomas. Others have noticed that the court’s move to a remote format has made Thomas almost loquacious. His ability to get to the core of the issue was illustrated by a question for the employees’ attorney, Jeffrey Fisher. Fisher was trying to argue that the employees’ job duties, which included teaching weekly religion classes and supervising students during Mass, were insufficiently religious for them to be considered ministers. This led Thomas to ask if the employees performed the same religious functions in a public school that they did in the Catholic schools, would it “be a violation of the Establishment Clause?” Fisher responded that it would be. Thomas responded, “don’t you think it’s a bit odd that – that things that violate in the Establishment Clause, when done in a public school, are not considered religious enough for Free Exercise protection when done in a parochial school?”

The trouble did not end there for Fisher. Justice Alito asked him if a teacher in a Catholic school only taught religion classes, whether the ministerial exception would apply. Fisher responded that they “would not be a minister in that case” because the teacher would not be in a position of “spiritual leadership of the congregation.” At that point, Fisher might have also lost the vote of Justice Kagan. In response, she said she thought that such a teacher “is protected by the exemption” and that she understands that sometimes teachers might have to teach other subjects making it difficult to “draw the line” between a full-time religious teacher and a “half” or “quarter” time religious teacher.

The teachers had placed great emphasis on the fact that they were not in significant positions of leadership and were not required to be Catholic. Neither argument appeared to gain any traction with the court’s conservatives or to be compelling to either Justices Breyer or Kagan. On the question of leadership, Breyer expressed concerned that in some religions “everyone” has a position of authority. Who should count as minister for those faiths and how could the court provide guidance that wouldn’t require courts to “meddle” too much in religion? Likewise, Justice Kagan wondered why a yeshiva couldn’t hire a non-Jewish expert on the Talmud to instruct on what the Talmud teaches and not have that person qualify under the exception.

In the end, four justices—Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh—appeared willing to grant religious institutions broad discretion to decide for themselves who counts as a minister. Chief Justice Roberts also seemed to favor the schools. He, for instance, was worried about judicial entanglement and requiring titles common in one faith, Protestant Christianity, to be used by others to count employees as ministers. Justice Alito even said he would jettison the phrase “ministerial exception” because it was discriminatory. However, given Robert’s distaste for 5-4 opinions, it would not be surprising to see him work to construct a 7-2 majority by bringing Breyer and Kagan alongside to craft a decision in favor of the schools but not going as far as the court’s conservatives would prefer. Regardless, you would rather be the schools than the teachers after Monday’s oral argument.

Joshua Dunn is professor of political science and director of the Center for the Study of Government and the Individual at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs.

By: Joshua Dunn

Title: Justices Hear Arguments in L.A. Catholic Schools Case – by Joshua Dunn

Sourced From: www.educationnext.org/justices-hear-arguments-l-a-catholic-schools-case-morrissey-berru-biel/

Published Date: Tue, 12 May 2020 14:41:17 +0000

No comments:

Post a Comment