Imagine a 6th-grade math teacher with high hopes for her students. Let’s call her Ms. Rodriguez. She wants her students to find joy in the beauty and complexity of math, make connections to the world around them, and master the skills and content they’ll need to succeed in middle and high school, college, and beyond. She believes that each one is capable of rigorous study and is committed to doing all she can to prepare them.

Imagine a 6th-grade math teacher with high hopes for her students. Let’s call her Ms. Rodriguez. She wants her students to find joy in the beauty and complexity of math, make connections to the world around them, and master the skills and content they’ll need to succeed in middle and high school, college, and beyond. She believes that each one is capable of rigorous study and is committed to doing all she can to prepare them.

But in a typical class of 25 students, she’s finding that as few as five can keep up with 6th-grade work. One day, after her students struggled with adding and subtracting decimals, she sensed that most of them hadn’t quite mastered decimal place value in the 5th grade. So she found a suitable lesson online and retaught place value—after all, you can’t hope to add decimals accurately if you can’t keep your tenths and hundredths straight. Her students caught on quickly and were relieved by the refresher.

By chance, the principal dropped in for an observation that day, and the feedback wasn’t good. Stick to the 6th-grade curriculum, he said. That’s what will be covered on the end-of-course exam, so that’s what students need to be taught. There won’t be time enough to cover much else.

Ms. Rodriguez believes in keeping expectations high. But she doesn’t see how students will ever meet 6th-grade standards if she can’t help them address unfinished learning from elementary school that is foundational to middle-school math. Gaps in learning lurk beneath the surface, and math instruction builds on itself each year. By only looking at the current year’s curriculum, how will her students ever master all they need to know?

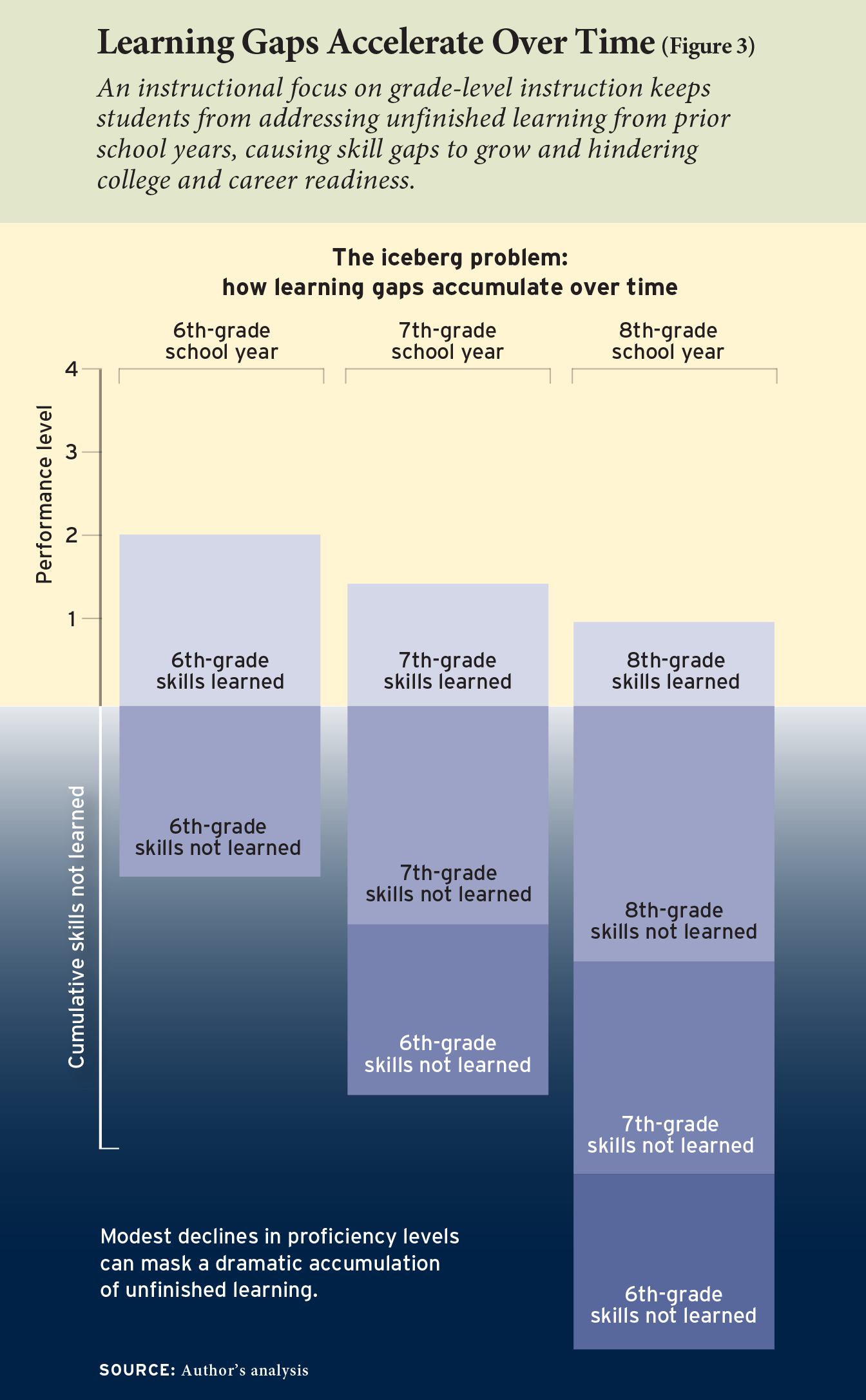

This is what the organization I lead has identified as the “Iceberg Problem,” and it’s what inspired us to create a personalized-learning model for middle-grade math eight years ago. That program, Teach to One, provides students with individualized instructional programs each day that integrate teacher-led instruction, collaborative learning with peers, and virtual online study. Our goal is the same as Ms. Rodriguez’s: for students to access the right lesson, in the right way, based on where they are starting and where they need to go.

We expected to run into a number of barriers that we would need to overcome if we were to be successful. We would need to raise capital, hire top-notch academicians and technologists, find interested schools, and navigate the myriad of operational complexities that can arise in any school environment—unfilled staff positions, uneven teacher quality, frequent leadership transitions, politicized decisionmaking, and unreliable technology infrastructure, to name a few.

Then came another barrier that we did not anticipate, which has emerged as one of our most formidable challenges.

It is that in math, today’s assessment and accountability policies may be inadvertently working against the interests of the very students they were designed to help.

High Expectations Matter, And…

The shift to more rigorous college- and career-ready standards has been one of the biggest policy developments in recent decades. Federal education legislation adopted in 2001 under No Child Left Behind and amended in 2015 under the Every Student Succeeds Act requires each state to administer annual math and reading tests aligned with grade-level standards for grades 3 through 8 and at least once in high school. The cumulative impact has set more consistent expectations for students based on benchmarks pegged to a college- and career-readiness trajectory and yielded progress in several areas, including greater transparency into achievement gaps between student subgroups, increased clarity for teachers on what students need to stay on a college- and career-ready path, and more objective information for families on whether students are reaching key educational milestones.

But in math, the subject our organization knows best, these well-intended standards and measures don’t always consider the diverse needs of individual learners to encounter material and progress at an optimal pace. To be sure, keeping expectations high for all students is critical—and for students from historically disadvantaged communities, there is ample evidence that many schools do not expect nearly enough. But within an individual class, an on-grade lesson for one student may be far out of reach, while that same lesson for another student may be too easy. Assuming that grade-level content is what’s best for everyone fails to acknowledge the reality that individual students have different levels of background knowledge.

When students miss key steps along the prescribed grade-level path, or learn at a pace that is faster or slower than state standards anticipate, the standards alone do not provide guidance to teachers on where to focus instruction. Instead, policies signal to a 7th-grade teacher, for example, that all 7th-grade students should be taught 7th-grade content—whether students happen to be performing at grade level or not.

For students who never fell behind, 7th-grade materials may be perfectly appropriate. But for those who may have missed key concepts along the way, trying to cover 7th-grade material when key concepts from 5th or 6th grade weren’t quite mastered can cause learning gaps to accumulate. The pattern repeats, year after year, as they fall farther away from the college- and career-ready track.

Few can credibly argue that a policy orientation focused on annual grade-level mastery is working. Only 34 percent of American students in 8th grade met the proficiency level or above in math based on the 2019 administration of the National Assessment of Educational Progress, with historically disadvantaged student groups hitting this target at less than half the rate of white students. These middle-grade math woes are often rooted in the elementary years, where one in five 4th graders fell into the lowest tier of math performance, well below grade level.

What are middle-school math teachers like Ms. Rodriguez to do when the grade-level material they must teach depends on foundational knowledge students do not have? How exactly are teachers supposed to deliver an impactful lesson on quadratic equations when many of their students do not understand exponents?

There is an acute tension between an instructional program that is best for each student to ensure they are ready for college and career and an underlying policy context rooted in grade-level expectations. The mathematical skills required for students to engage with grade-level material in middle school and high school are built on a deep, conceptual understanding from previous years. And although many students arrive at middle school without these foundational skills, state and federal policy systems incentivize teaching to grade-level standards to curtail low expectations and inequitable outcomes.

We do not see strong evidence in the field or in research that, in math, strict adherence to grade-level content is best for all students.

There is a path for far more students to achieve college and career readiness, but it requires systematically addressing students’ unfinished learning from prior years. Simply demanding that teachers somehow figure out both how to address students’ unfinished learning from previous years and how to cover all grade-level material may be causing some students to fall farther behind.

Math: The Jenga Game of Subjects

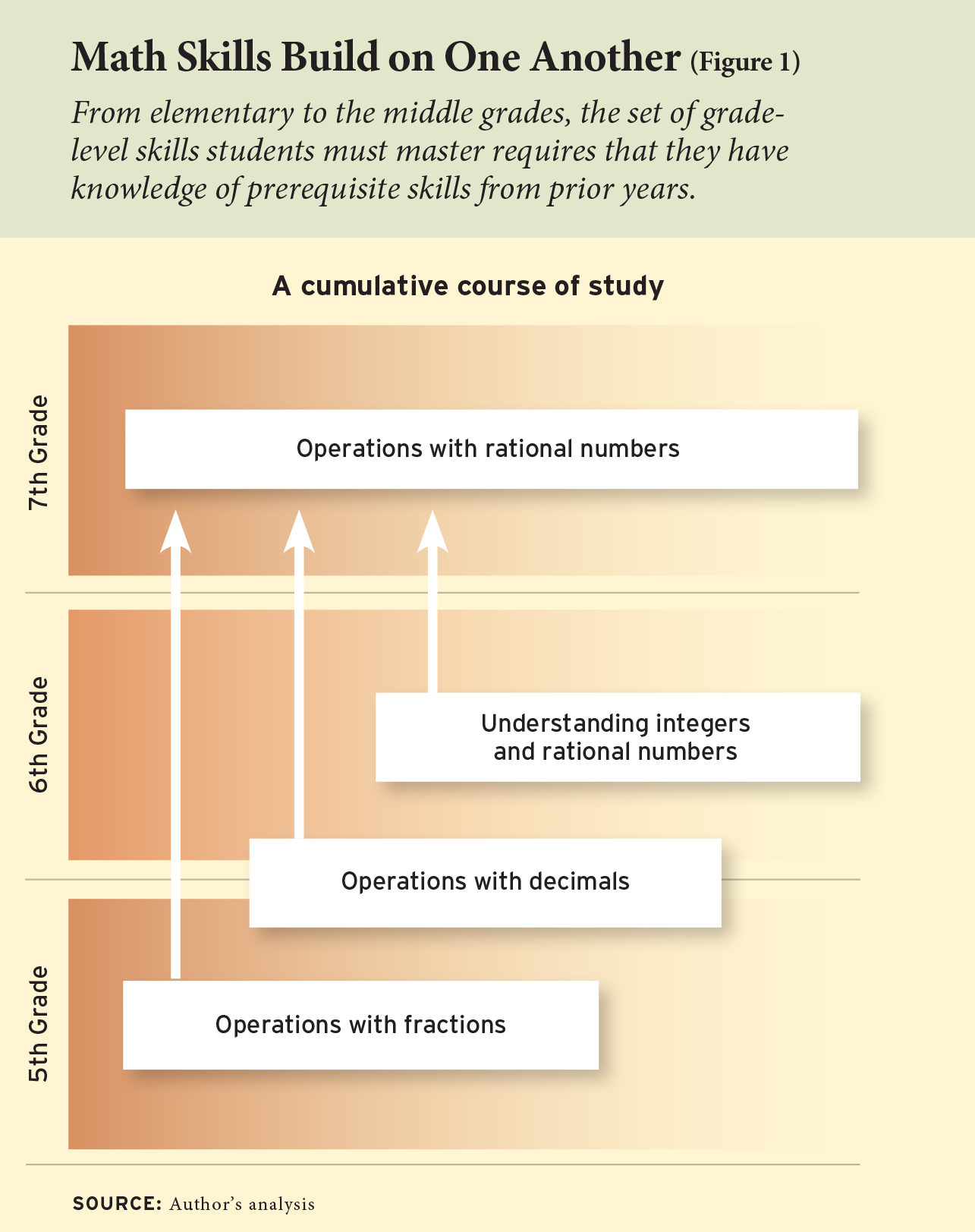

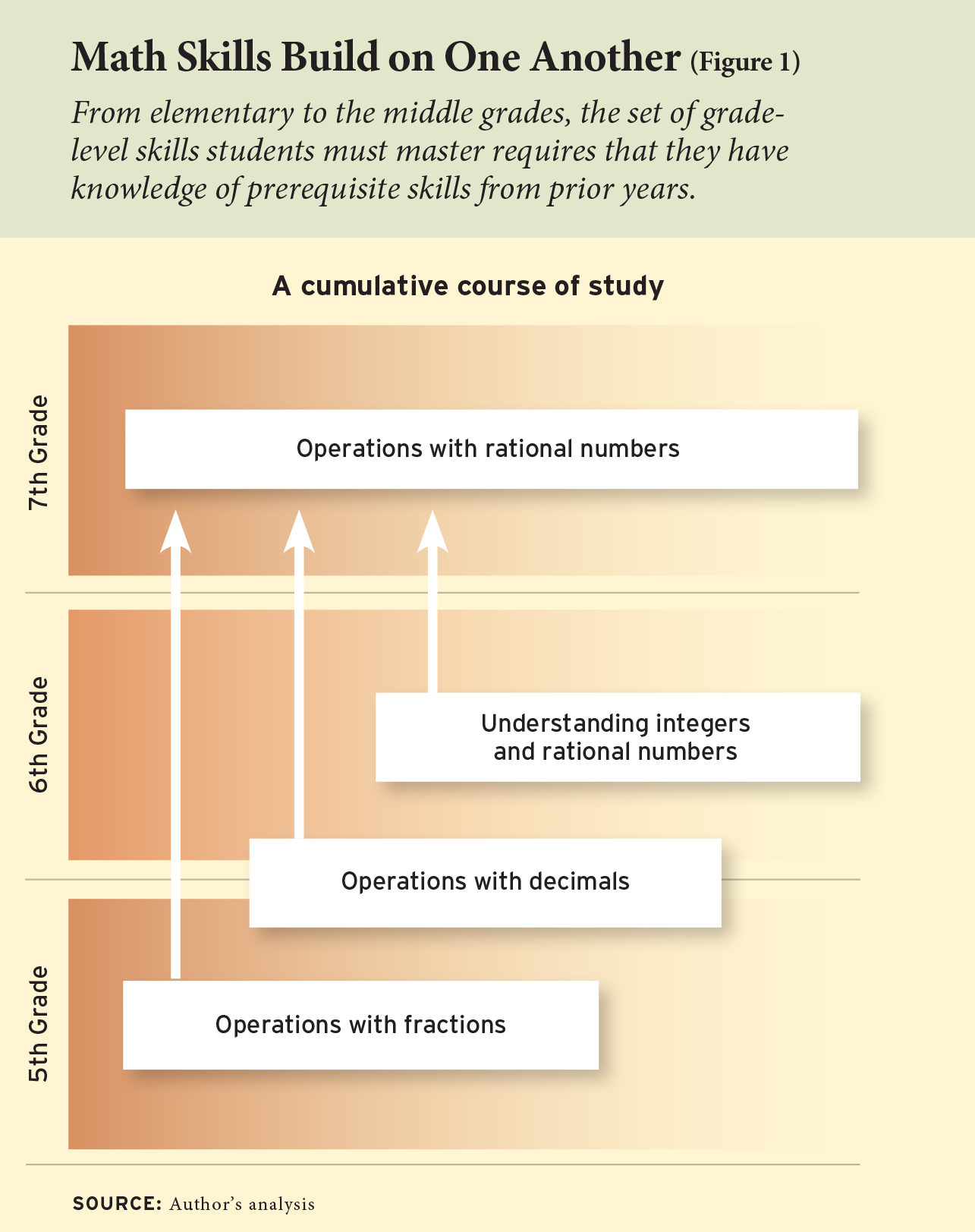

Math is cumulative, with new learning resting atop earlier mastery. Year by year, students learn interconnected concepts in a coherent progression, building a foundational body of knowledge that undergirds new understanding in the grades ahead.

For example, 7th-grade math typically includes performing basic operations with rational numbers. For students to know how to do that, they need to have mastered several key skills and concepts from 5th and 6th grade, including understanding integers and rational numbers and performing basic operations with decimals and fractions (see Figure 1).

When a student starts the school year with unfinished learning from prior years, the challenge of both covering grade-level material and addressing unfinished learning can be daunting. For example, 8th graders are expected to learn about multistep equations during the course of the school year, even though some students begin the year not having mastered critical predecessor skills such as solving simple equations, operations on rational numbers, or adding and subtracting algebraic expressions.

Imagine being asked to solve 2(x + 1) – x = 5 without understanding the order of operations or how to work with x. It can’t be done. And lessons focused on multistep equations would be lost—alongside the foundational lessons missed the first time around.

So would precious instructional time.

Of course, high-performing math teachers and thoughtful curriculum materials build in opportunities to revisit important concepts, including through “spiraling” questions that reinforce recent skills and topics throughout the school year. But what happens when the missing knowledge is from several grade levels ago? In the example above, each of these component skills could take three to four days to cover sufficiently—and they are only the predecessors for one grade-level skill. For many students, the learning gaps they are expected to bridge in one year in order to attain grade-level proficiency are so substantial that meeting that benchmark in that time period is highly improbable.

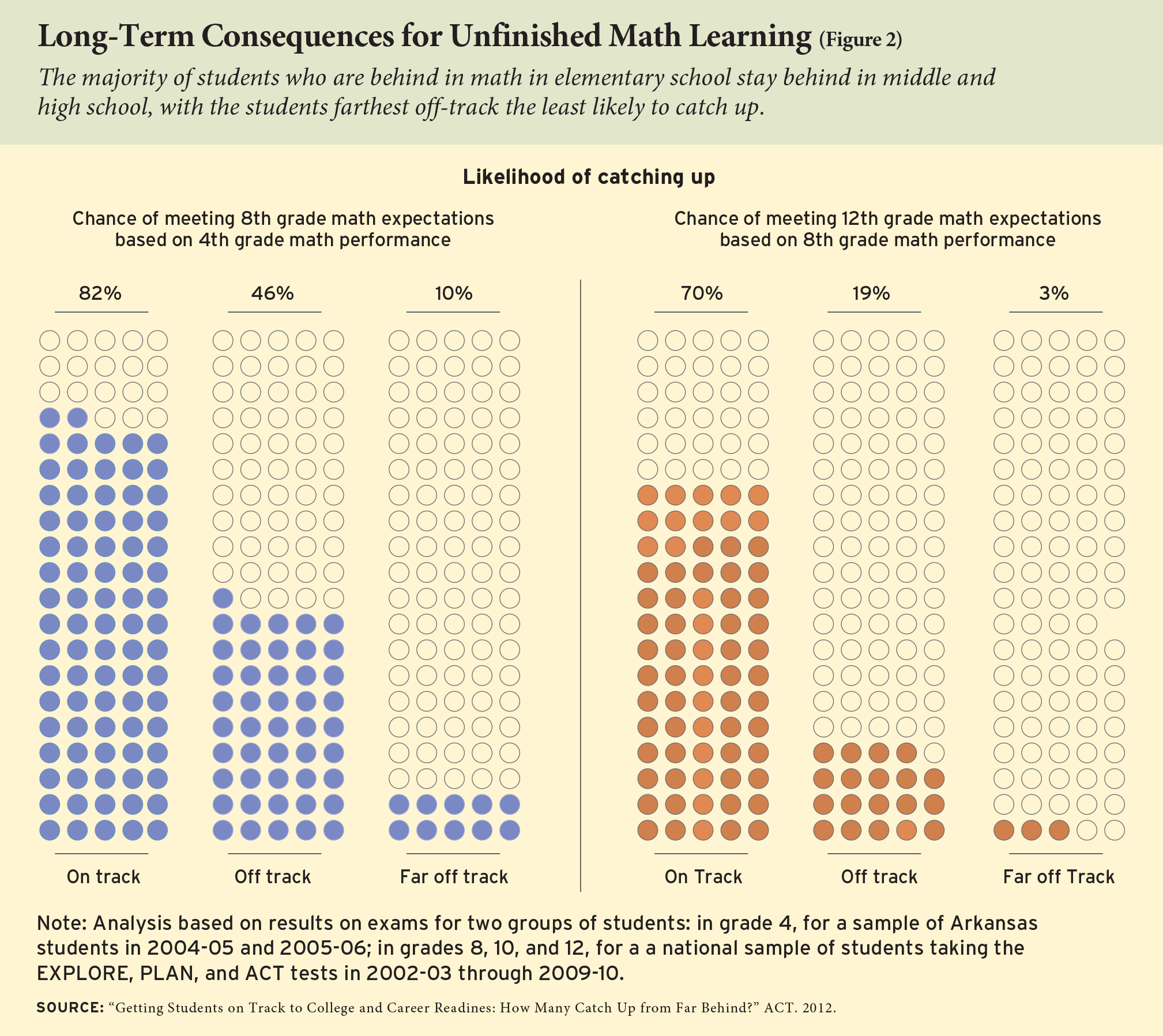

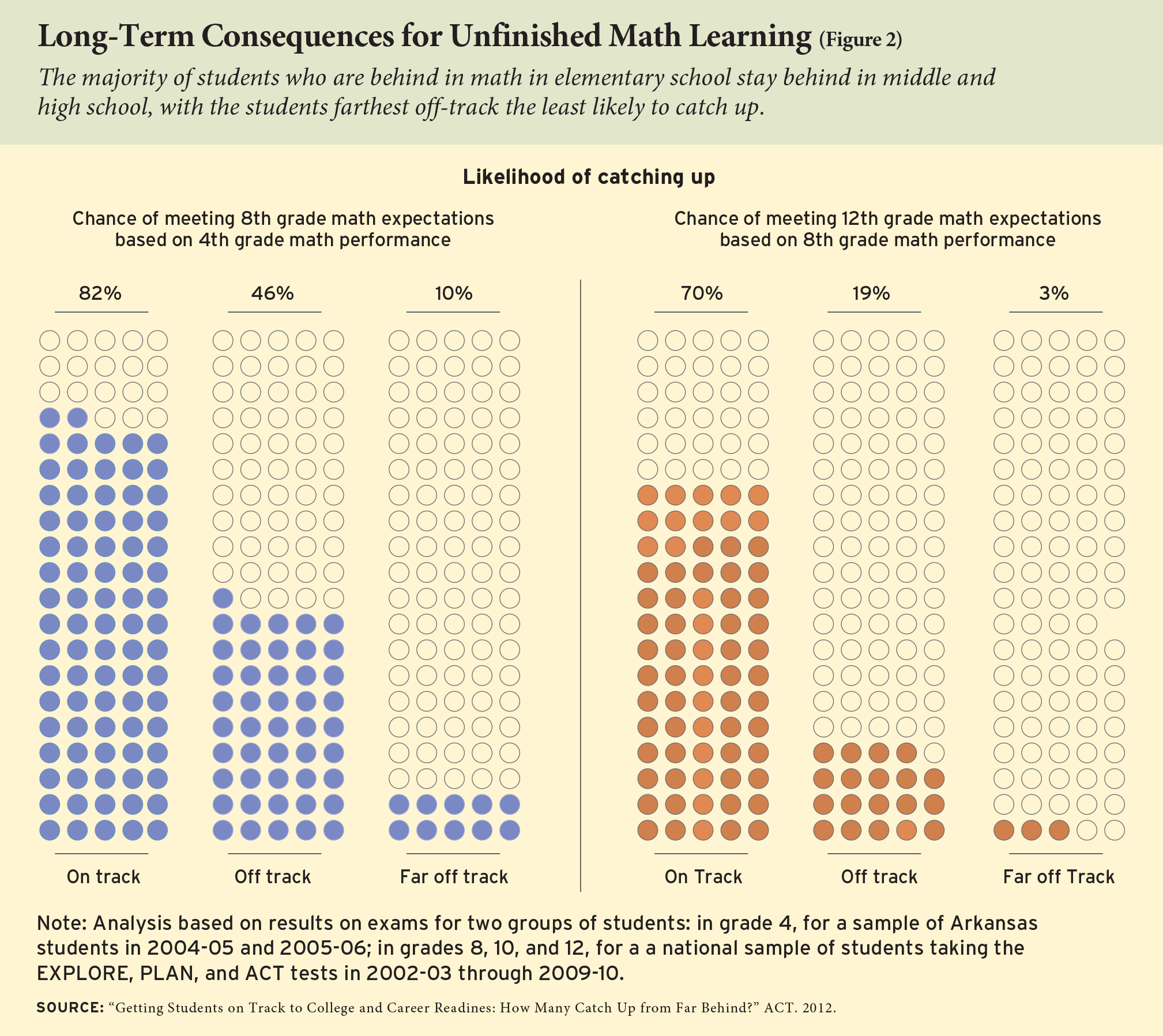

Longitudinal studies of individual students over time can show more precisely how students who fall behind are likely to stay behind. In a 2012 study conducted by ACT, researchers tracked math test results from tens of thousands of students to calculate their math skills and relative chances of reaching grade-level expectations in the 8th and 12th grades. Students below grade level in math in 4th grade had just a 46 percent chance of reaching grade-level expectations in 8th grade; those below expectations in 8th grade had a 19 percent chance of reaching 12th-grade expectations (see Figure 2). These figures were even more daunting for the lowest-scoring students, whose chances of meeting expectations for the 8th and 12th grades were 10 percent and 3 percent, respectively. This same study also found that the lowest-scoring students were much more likely to attend high-poverty schools.

There are multiple reasons why it can be so hard for lower-performing students to catch up in math. In some communities, there are particular challenges in recruiting, developing, and retaining high-quality math teachers, many of whom have more attractive employment opportunities in other sectors. In other communities, ongoing leadership transitions at the school or district level can lead to continual shifts in organizational direction. Poverty-related issues such as trauma, violence, and nutrition are all highly relevant to student academic performance. So, too, are the expectations that adults have for students.

While the impact of these and other factors are well documented, an underlying policy landscape that incentivizes grade-level instruction may also be playing a key role in preventing students from getting back on track.

When Policy Meets Practice

Under federal law, all students in grades 3 through 8 must take a statewide summative assessment in math that is aligned to their enrolled grade level to form the basis of states’ accountability systems. All 6th graders take the 6th-grade test, all 7th graders take the 7th-grade test, and so forth, with only a narrow set of exceptions.

These exams are used as key components across many evaluation and decisionmaking activities. All states are required to set goals based on test results, including to increase the share of students who meet standards in reading and mathematics, accelerate progress of underperforming subgroups, improve graduation rates, and identify low-performing schools for varying levels of support and intervention. Some states have opted to include tests among measures of student growth in teacher-evaluation systems. Local communities review their test performance closely, and many district and school administrators believe their career success is dependent upon success on annual assessments. For many charter schools, meeting test-based goals for proficiency and student growth can mean the difference between closure and continued existence.

States have discretion to choose which test to use. All the tests, though, are required to be aligned to grade-level standards that reflect a college- and career-ready academic trajectory. Few, if any, of the actual test questions relate to anything other than the standards that match each student’s enrolled grade level. The idea is to have the equivalent of an educational “dipstick” so that decisionmakers and the public can have an objective, comparable view of where each student performs in relation to state expectations.

The combination of grade-level tests and high-stakes accountability interjects reliable data into the decisionmaking process of administrators, teachers, parents, and policymakers. It ensures that school communities remain focused on measurable student outcomes and highlights profound inequities across and within schools and districts that can require public response. But as currently constructed, there’s a significant tradeoff: Teachers face pressure to focus instruction on the grade-level material appearing on the end-of-year test, regardless of students’ background knowledge. And in math, for those students whose incoming preparation is poorly matched to standard grade-level expectations, these incentives can produce the opposite of their intended effect.

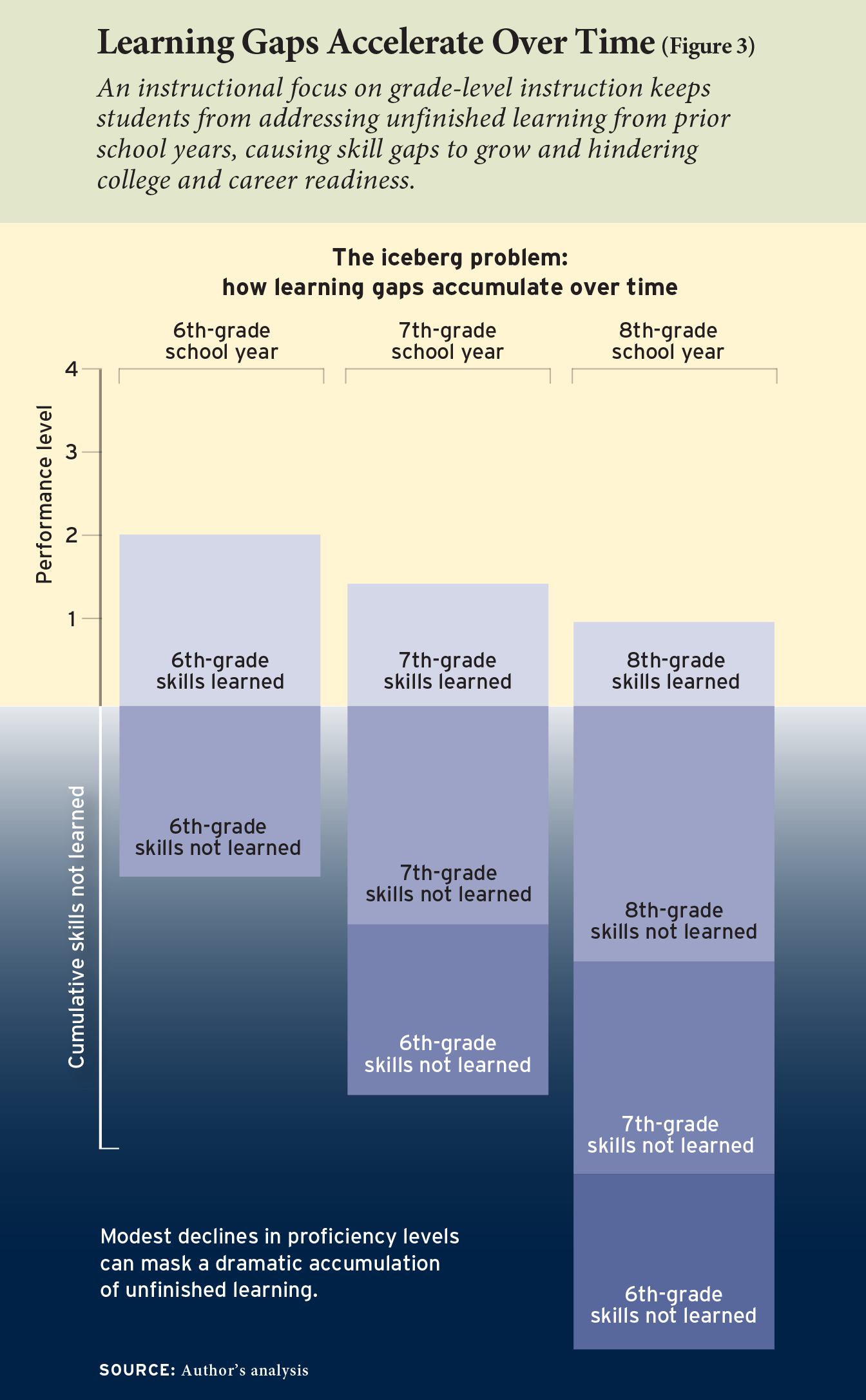

When a 6th-grade student is taught 6th-grade material, some of those skills will be learned and some will go “unlearned” for a variety of reasons (e.g., lack of predecessor knowledge, uneven teacher quality, student absences). The next year, as the focus of accountability shifts to the 7th-grade assessment, the unlearned skills from 6th grade remain unaddressed, even though those skills may be essential to mastering 7th-grade content. By 8th grade, even more learning gaps accumulate so that by the time a student enters high school, the student is simply unprepared for more advanced mathematical topics.

In middle-grade math, while the gaze of policymakers is focused on how students are performing relative to grade-level assessments, learning gaps continue to accumulate below the surface, making longer-term success harder to achieve. This is the “Iceberg Problem” illustrated in Figure 3.

The authors of the Every Student Succeeds Act likely foresaw the value in measuring growth outside of grade-level standards, as the law permits states to adopt assessments that also “measure academic proficiency and growth using items above or below the student’s grade level.” However, subsequent guidance from the U.S. Department of Education specifies that if states design tests to include additional measures of off-grade performance, they must still measure and score students’ on-grade performance accurately. Any off-grade measures would not satisfy the law’s accountability provisions for student performance. As a practical matter, due to the broad set of standards at each grade level and pressures to reduce test time and length, most summative state assessments are almost exclusively focused on grade-level content.

The federal policies that undergird statewide assessment and accountability systems send an unmistakable signal to middle-grade math teachers: focus your instruction on the grade-level standards.

Putting Personalization to the Test

Teach to One is just one approach schools use to meet the unique needs of each student. It is designed around 300 mathematical skills and concepts that connect basic numerical understanding to college-readiness benchmarks.

The program uses ongoing assessments of students’ competencies to tailor instruction. A customized software program assesses individual skill levels and creates customized skill libraries, units of study, and tests and quizzes. Day to day, students learn in extended class periods that include instruction from teachers, group work, individual practice, and a brief daily assessment of progress called an “exit slip.” Up to three times a year, they take the Measures of Academic Progress, a computer-based adaptive test that measures learning growth over time.

The idea is to ensure that students are continually learning within their “zone of proximal development,” where the material they are expected to learn is appropriate given what they already understand and where they need to go. With the right support, students working in the “zone” can master content that was previously out of reach. This approach can fill knowledge gaps and catch up students who are lagging, as well as accelerate learning and engage students ready to advance beyond grade-level material. Of the students in grades 6 though 8 who have participated in Teach to One over the past three years, about two thirds started the school year at least two grade levels behind, and 9 percent were four grade levels behind. Just 2 percent were ahead of their grade level.

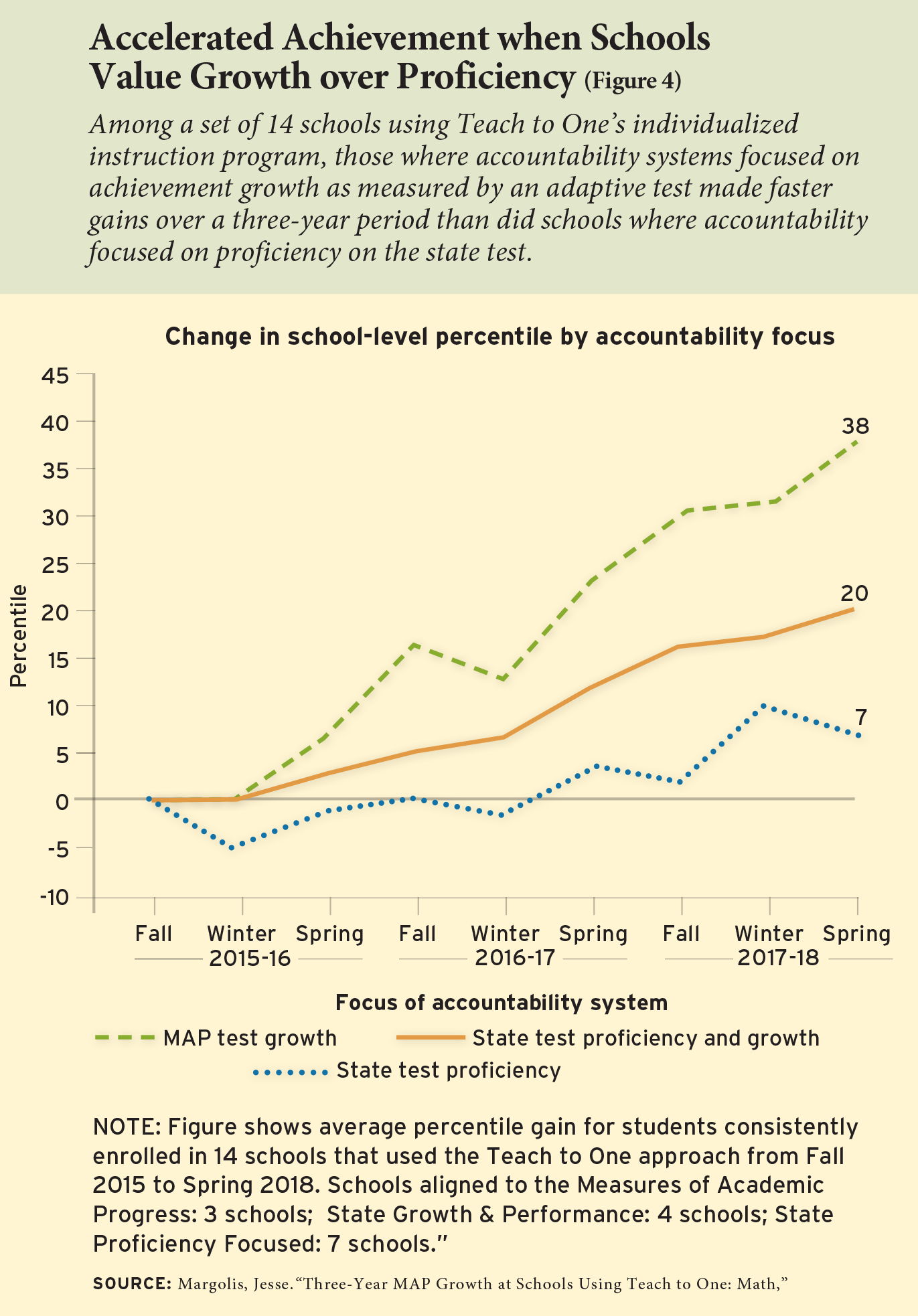

In its eight years, Teach to One has operated in districts and schools with different philosophies regarding the role of grade-level material, notwithstanding federal signals. In schools where accountability systems imposed at the district or school level are based on growth measures that cross multiple grades, the program can tailor a personalized curriculum for each student that includes a mix of pre-grade, on-grade, and post-grade material, depending on his or her unique starting point. By contrast, in schools focused on students’ performance on annual state assessments, leaders have often asked us to weigh students’ personalized curricula more heavily toward grade-level content for the year. This can mean leaving important pre-grade gaps unaddressed.

Our preference would be to help schools fill pre-grade gaps and cover grade-level material. But a 180-day school year is often not enough to make up for multiple years of unfinished learning. Absent clarity on how to reconcile this tension, schools can struggle to make hard choices about what to prioritize.

This challenge was highlighted in an experimental study of Teach to One at five schools in New Jersey published in 2018. During the study period of 2015 to 2018, different schools requested a variety of program adjustments that either emphasized or deemphasized grade-level content. As a result, researchers were unable to draw any conclusions on the overall impact of the program as it was designed.

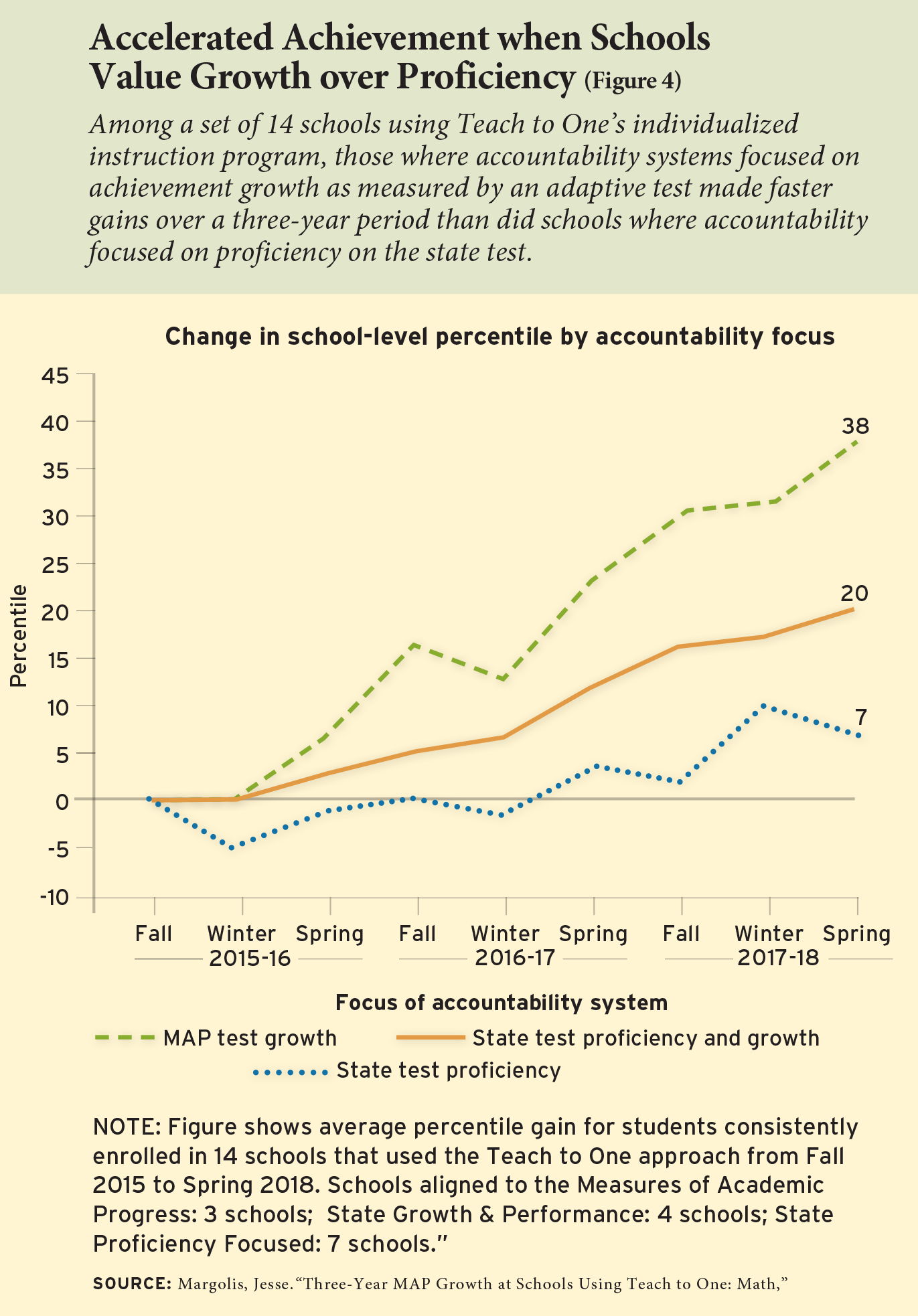

What can happen when schools make a clear choice to prioritize learning growth over grade-level exposure? A 2019 study looking at progress on the Measures of Academic Progress assessment compared the growth of Teach to One students at 14 schools over three years to national averages. It found that Teach to One schools whose accountability systems focused on growth made stronger gains than schools whose accountability systems focused on proficiency (see Figure 4). The study also found suggestive evidence that schools tended to see stronger gains when the math content presented to students matched their tested grade level from the beginning of the year.

While firm causal evidence of the impact of grade-level assessment and accountability has yet be established, these findings should be viewed as an important contrast to the evidence base for what policy currently promotes: providing all students with grade-level content, regardless of their starting point.

Researchers explored the effects of giving students content far outside their current skill level after a policy push in the early 2000s placed many 8th-grade students in Algebra who would have otherwise taken a pre-algebra 8th-grade math course. In 2008, Tom Loveless found that very low-achieving math students enrolled in Algebra courses performed about seven grade levels below their peers on the National Assessment of Educational Progress and struggled with questions that tested elementary-level understanding. Another study found that low-achieving students pushed into algebra did less well in subsequent math courses throughout high school, especially in geometry (see “Solving America’s Math Problem,” research, Winter 2013).

There is little evidence to suggest that in math, low-performing students pushed into grade-level content without appropriate support and attention to prerequisite skills will be better off in the long run. Yet today’s policy landscape incentivizes just that.

Fixing the Iceberg Problem

This is not a call to reverse the principles of standards, accountability, rigor, transparency, and equity that form the basis of education policy and practice today. These are essential elements for building a school system worthy of the students it serves. The historical roots of our inequitable education system run deep, and the need for guardrails within federal policy to mitigate and, ultimately, reverse this pernicious legacy is essential.

But it is a candid acknowledgement of the tradeoffs and costs that a focus on annual grade-level expectations creates. In math, preparing students for college or a career requires honestly confronting any gaps in learning that lie beneath the surface. That does not mean lowering expectations for students; rather, given the inherently sequential nature of mathematics, it means designing viable paths that can connect students from where they are starting from to where they need to be.

Today’s policy landscape is constraining these kinds of innovations.

I have seen in our work that individualized instruction and high expectations can go hand in hand, and that if we are able to identify and address unfinished learning from prior years, students can advance more quickly and successfully toward their goals. I hope our experience can help to spur the development of more innovative learning models that seek to address individual students’ learning needs. Teach to One is by no means the only way for schools to do that. Ensuring all students can access a tailored path to college and career readiness will require the development of a variety of innovative learning models with different philosophies and pedagogical approaches underpinning them.

There are several steps states and districts can take to address students’ unfinished learning while working within the current framework of federal law. They can measure learning growth more comprehensively by using adaptive assessments that adjust in difficulty based on student responses. They can also adjust their accountability systems to emphasize proficiency at key grade levels, as opposed to annually. States might also create space for innovation (as Texas has done with its Math Innovation Zones program) so that new learning models can be properly implemented and tested in ways that operate largely outside of the current grade-centric system.

But in the longer term, policymakers and advocates will need to develop and advance a shared vision for what one day might be a new assessment and accountability system. It will need to be one that preserves our current values and commitments without promoting instructional practices that prevent students from accessing academic paths that might better enable their longterm success.

Joel Rose is co-founder and chief executive officer at New Classrooms, which published The Iceberg Problem, from which this essay is adapted.

more news https://northdenvernews.com

The 43rd governor of Florida and the president and chairman of the Foundation for Excellence in Education, Jeb Bush, joins Education Next Editor-in-chief Marty West for the 200th episode of the EdNext Podcast. Governor Bush discusses his experience managing crises, as well as some of the best practices to continue education during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The 43rd governor of Florida and the president and chairman of the Foundation for Excellence in Education, Jeb Bush, joins Education Next Editor-in-chief Marty West for the 200th episode of the EdNext Podcast. Governor Bush discusses his experience managing crises, as well as some of the best practices to continue education during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Imagine a 6th-grade math teacher with high hopes for her students. Let’s call her Ms. Rodriguez. She wants her students to find joy in the beauty and complexity of math, make connections to the world around them, and master the skills and content they’ll need to succeed in middle and high school, college, and beyond. She believes that each one is capable of rigorous study and is committed to doing all she can to prepare them.

Imagine a 6th-grade math teacher with high hopes for her students. Let’s call her Ms. Rodriguez. She wants her students to find joy in the beauty and complexity of math, make connections to the world around them, and master the skills and content they’ll need to succeed in middle and high school, college, and beyond. She believes that each one is capable of rigorous study and is committed to doing all she can to prepare them.

The Director of the Public Policy Research Lab at LSU’s Manship School of Mass Communication, Michael Henderson, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss Louisiana’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic, and how the public is responding to the state’s stay-at-home order.

The Director of the Public Policy Research Lab at LSU’s Manship School of Mass Communication, Michael Henderson, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss Louisiana’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic, and how the public is responding to the state’s stay-at-home order.