News…. browse around here

The president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, Mike Petrilli, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss the results of the 2021 Virginia Governor race, and what the election of Glen Younkin could signal for school choice moving forward.

The president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, Mike Petrilli, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss the results of the 2021 Virginia Governor race, and what the election of Glen Younkin could signal for school choice moving forward.

Follow The Education Exchange on Soundcloud, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Stitcher or here on Education Next.

— Education Next

The post The Education Exchange: “White Supremacy” Winds Up on a School’s List of American Principles appeared first on Education Next.

[NDN/ccn/comedia Links]

News…. browse around here

Last week’s elections were a turning point in the fraught debate over how race and racism are taught in America’s schools. No, the backlash against critical race theory wasn’t the only issue that mattered in Virginia’s gubernatorial election. The Republican candidate’s surprisingly strong showing in New Jersey’s governor’s race (where CRT wasn’t even on the menu) suggests that the general political environment posed ample challenges for Democrats. That’s not unusual, considering that opposition parties often do well in off-cycle elections. Nor was the curriculum controversy the only education issue stoking parents’ anger. Just as powerful was frustration with lengthy school closures, which were worse in Virginia and New Jersey than almost anywhere else.

Still, the political commentariat seems to agree that the way Virginia Democrat Terry McAuliffe handled the CRT controversy was a case study in exactly what not to do. Not only did he make a terrible gaffe in saying in a September debate that parents shouldn’t be telling schools what to teach, he doubled down by repeatedly asserting that the whole issue was nothing but a racist dog whistle.

It doesn’t take a political genius to understand that this wasn’t a winning message for parents with concerns over what they saw being taught in their children’s schools. As Yascha Mounk wrote in the Atlantic, “you can’t win elections by telling voters their concerns are imaginary.”

And as both Ross Douthat and David Brooks have pointed out, while Virginia second graders are nowhere close to being force-fed CRT, recent years have brought an aggressive shift in how progressives talk about race and racism, and that has inevitably been filtering into the schools. Indeed, Rick Hess has documented many examples just from the Commonwealth of Virginia. In Loudoun County, for instance:

…“anti-racist” trainings taught teachers to reject “color blindness,” address their “Whiteness (e.g., white privilege),” and recognize that “independence and individual achievement” are racist hallmarks of “white individualism” (as is a commitment to “self-expression, individual thinking, personal choice”).

Nobody knows for sure how prevalent this sort of woke training and curriculum is. But even if a school system hasn’t adopted the (CRT-inspired) 1619 Project, or put Ibram X. Kendi or Robin DiAngelo on their summer reading lists, it’s not hard to imagine well-meaning teachers making questionable statements in the classroom. As Andy Rotherham told The 74, “right now there is enormous demand but little quality control in the [diversity, equity and inclusion] industry, and teachers are freelancing. That’s a bad mix. This is complicated, and you don’t want teachers using whatever they found on Pinterest last night or just learned at a one-hour workshop.”

Just last week my own eighth grade son came home (from a Maryland public school) with a history assignment that listed “white supremacy??” among a number of “American values.” In my opinion, this is an inflammatory and wrongheaded way to address America’s history of slavery and racial discrimination. My point isn’t to debate that particular assignment but to illustrate how pervasive this sort of thing may be. As John McWhorter wrote in the New York Times this week, “if it’s not critical race theory, it’s critical race theory-lite.”

So Democrats failed a major test in contending that CRT is absent from our public schools, rather than listening to parents’ concerns.

Yet they may take hope from the likelihood that Republicans will also mess up this issue. In fact, that’s already starting to happen in the form of blatant overreach.

As is often the case, Texas is leading the way, with a highly questionable investigation of books in school libraries—one that’s a little too reminiscent of the McCarthy era—on top of a highly problematic anti-CRT bill that became law last spring.

Few parents may want woke curriculum, but how many want book banning instead? Or for their kids to see “both sides” of the Holocaust? The goal should be to provide our children with a well-rounded liberal education that encourages them to understand the facts, weigh multiple perspectives, search for truth, and think for themselves. The goal isn’t to replace one form of indoctrination with another.

Indeed, conservative writer David French makes a compelling argument that right-wing illiberalism is emerging as a significant problem, especially in red states like his own Tennessee. “An increasing number of politicians, lawyers, and activists,” he writes, “are responding to fears of left-wing intolerance with their own efforts to censor, suppress, and cancel.” Some are afraid that depictions of Ruby Bridges standing up to white supremacists (including one by Norman Rockwell!) will make kids today feel bad; others want Toni Morrison’s Beloved out of high schools because of its unsparing portrait of slavery and sexual violence. (That’s the point, of course.)

What Republican politicians should understand is that most of their own voters want schools to forge a reasonable middle path. Kristen Soltis Anderson led a fascinating survey for the PIE Network recently, which she and others have been writing about. Overwhelmingly, both Democrats and Republicans want history to be taught warts and all. More than three-quarters of Republicans and almost all Democrats agreed that “we should acknowledge the terrible things that have happened in our nation’s history regarding race so students can learn from them and make the future better.” Three-quarters of all voters also support “adding more books in English classes by authors who are Black, Indigenous, or people of color.”

If Republicans keep going after Ruby Bridges and Toni Morrison and Norman Rockwell, those independent voters are going to swing back in the other direction. And more than a few GOP voters are bound to have second thoughts. As well they should.

Is there a way through all this, a way that’s right for American kids and acceptable to the great majority of their parents?

I surely don’t have all the answers. But somehow we need to find a way to delineate between the various flavors of overly woke curricula that are offending so many parents and more thoughtful approaches that seek to teach history honestly and comprehensively, add diverse voices to the English literature canon, and help all students see themselves in America’s story. The laudable Educating for American Democracy roadmap goes a far distance in that direction; so too do the exemplary U.S. history and civics standards in the five (red and blue) states that earned A’s in our recent reviews. Not to say that it’s easy. It’s surely harder than fighting another culture war. But it’s the work we are called to do.

Michael J. Petrilli is president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, visiting fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, and an executive editor of Education Next.

This post originally appeared on the Fordham Institute’s Flypaper blog.

The post On Race in the Classroom, Republicans Risk Overreaching appeared first on Education Next.

[NDN/ccn/comedia Links]

News…. browse around here

Terry McAuliffe surely blundered when he declared—out of context though it was taken—that “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach,” thereby handing Glenn Youngkin a perfectly-timed campaign issue. Millions of parents in Virginia and across the land were already aggrieved by their schools’ mishandling of education during the Covid-19 pandemic, conscious that many school systems paid greater heed to the demands of their adult employees than the needs of their pupils. This caused huge learning losses for most kids and enormous challenges for parents. Lots of parents were also alarmed by reports that their schools were going to extremes in teaching about race, gender, sexuality, and other touchy or politically charged issues. At a time when the larger polity was already polarized, siloed, and jittery, it was a no brainer for Youngkin and his advisors to make this a winning issue.

Signals from other elections plus polling data also suggest that education has re-emerged as a top concern for much of the electorate. In response to which, House minority leader Kevin McCarthy has promised that the GOP will soon develop a “parents’ bill of rights” intended for Republican use in the midterm elections and beyond, as well as future action on Capitol Hill.

It’s too soon to know what will be in it, though undoubtedly it will make a big deal of parents’ right to select their children’s schools. One may hope it also includes a push for curricular transparency so that parents can readily see what their kids are being taught, not just in the three R’s, but also in civics, history, literature, and the less academic realms of social and emotional well-being, health, and values. Parents should know who is teaching and counseling their daughters and sons—their names, their training, their work experience, and (where relevant) their certification. Moms and dads also have every right to know what’s going on in their children’s schools by way of disciplinary policy and practices, building security, and the handling of awkward “social” issues (who uses which restrooms and locker rooms and plays on which teams), as well as such basics as what’s on offer in the lunchroom.

That’s all legitimate information for parents—and much of it is very difficult for most parents to find out today. Bravo for a “bill of rights” that takes up and runs with transparency as well as choice.

But how much farther should it go and is there a risk of going too far?

Indeed there is, which calls for bill-of-rights architects to strike a careful balance, something nearly unheard of at an unbalanced time. For education is not exclusively the province of parents any more than it’s the monopoly of the state—precisely the balance the Supreme Court struggled with a century ago in its landmark Pierce decision.

It’s a combination, a sort of hybrid, beginning with the truth that education is both a private good and a public good—as any economist will tell you. The child is not the creature of the state, yet society has an obligation to ensure that its next generation is adequately educated. That’s why every state has embedded that obligation in its constitution. That’s also why, for instance, states have compulsory attendance laws even as parents have the right to educate their kids at home. If they send them to school, as most do, they should have choices among schools, yet the state decides what is a school. Parents should of course select the school or schools that best suit their children but, having done that, should entrust things like curriculum to the schools and their educators. If parents are then unhappy with how it’s going in the school they chose, they should—and should be able to—change schools. But that’s not the same as meddling in the curriculum and pedagogy of their chosen schools or harassing the professionals who staff them.

Schools should be free to differ in dozens of ways, yet it’s reasonable for the state to verify that they all provide adequate learning outcomes in core subjects. That doesn’t mean all schools must use the same curriculum or pedagogy or follow the same philosophy to produce those outcomes. Again, it’s a balance, one easily thrown out of whack if, for example, the state doesn’t permit or overly constrains school choices, or if parents, having chosen, still interfere overmuch with how their schools go about it.

Parents have other options, too. They can—and many more should—run for the school’s board or the local school board. They can run for the state board of education, the town council, or the legislature. They can start their own charter or private schools, at least they can where this is permitted by law and where the state’s dollars follow children to the schools they actually attend. A nontrivial issue in Virginia is the Old Dominion’s extreme paucity of public charter schools—just seven at last count—due to a highly restrictive charter law, meaning that the overwhelming majority of Virginia families have no choices beyond their local school district. This means the political system builds up education steam without adequate escape valves. That leads to rancor, protests, and overheated campaigning rather than the creation of viable alternatives.

So let’s applaud the generous provision of quality school choices everywhere in the land. And let’s push for maximum school transparency. In pursuit of those ends, a parents’ bill of rights is a fine thing. But let’s also make sure that it can coexist with society’s responsibility to ensure that its next generation gets satisfactorily educated and the state’s obligation to ensure that that happens. Let’s try—let’s hope—to get this balance right despite the imbalances that surround us.

Chester E. Finn, Jr., is a Distinguished Senior Fellow and President Emeritus at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. He is also a Senior Fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution.

This post originally appeared on the Fordham Institute’s Flypaper blog.

The post A Parents’ Education Bill of Rights As a Fine Thing—Within Limits appeared first on Education Next.

By: Chester E. Finn, Jr.

Title: A Parents’ Education Bill of Rights As a Fine Thing—Within Limits

Sourced From: www.educationnext.org/a-parents-education-bill-of-rights-as-a-fine-thing-within-limits/

Published Date: Fri, 12 Nov 2021 16:57:59 +0000

News…. browse around here

During the pandemic, the federal government has provided unprecedented amounts of emergency aid to K–12 education. How can school leaders most effectively use these funds to overcome learning disruptions, give students the support they need, and position students and schools for future success? To tackle these queries, I reached out to Marguerite Roza, the director of the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University, author of Educational Economics: Where Do School Funds Go, to get her take on how to spend COVID-19 aid wisely and well. Here’s what she had to say.

—Rick Hess

Hess: Can you remind us how much Covid-relief money there’s been for K–12, what strings are attached, and who decides how it gets spent?

Roza: Sure. Congress basically went all-in on a grand experiment by cutting checks in three waves to send funds to districts to the total tune of roughly $3,750 per student—for a total of $189 billion—while asking for very little in return. Yes, the broad goal was to help students get back on track, but districts have virtual carte blanche in how they spend the money, and it is indeed the district that gets to decide. Just about any expenditure is fair game, including paying for new buildings, teacher bonuses, security contracts, staff stipends, COVID tests, electric buses, data systems, and more. Those are all real examples of district choices, by the way. The money must be spent by 2024. Districts have to make a spending plan, with fall due dates that vary by state; get it approved by the state ed. agency; and post it online.

Hess: What are some of the more promising ways you’ve seen these dollars spent?

Roza: We’re seeing districts adapt to help make sure students are returning—things like finding ways to transport kids during bus driver shortages, updating ventilation, creating virtual offerings where needed, and so on. These actions make sense as schools restart from pandemic shutdowns. And to get kids back on track, we’ve seen districts launch summer programs, tutoring, tele-counseling, longer school years, and more. Some districts are targeting one-time raises to address key shortage areas, like special education teachers, offering incentive packages to cover moving expenses plus retention bonuses, and paying stipends for teachers who take on extra work. These are promising pay innovations that run against the grain of the uniform step-and-column pay structure that’s dominated for decades. That’s not to say that every investment will be a success; some districts will need to pivot again. But where we see districts drilling down on student needs and nimbly solving the problems at hand, that’s good news.

Hess: What are schools doing that gives you pause?

Roza: Any investments that aren’t made on behalf of kids, like giving outsized across-the-board base-pay raises. Or spending on new facilities that won’t be completed in time to benefit today’s students, the ones impacted by the pandemic. Or when districts invest in the easy thing—like hiring more vice principals or paying forward on a security contract—not because they believe in the value but because it moves a lot of money quickly in a familiar way. Or using the money to backfill budgets that should have been rightsized years ago for enrollment drops that started long before the pandemic. (Ahem, Minneapolis, we saw what you did there using half your relief funds to stave off layoffs and program reductions.) We worry, too, about districts using this temporary money to hire a slew of new permanent staff because it sets them up to fall off a fiscal cliff.

Hess: What are a few of the more common mistakes you’re seeing?

Roza: We’ve created a list of six common mistakes that include making recurring commitments that bring a disruptive fiscal cliff and using federal funds to avert overdue cuts in a system that’s been losing kids for years. Also included is the risk of issuing problematic contracts that haven’t been vetted publicly and don’t include measurable milestones for the vendor. These kinds of contracts can get leaders in trouble down the road if not given proper attention. On equity, we suspect in hindsight some districts will have concentrated their relief funds in more advantaged schools, which can happen unintentionally, especially when positions get filled immediately in advantaged schools while vacancies linger in higher-needs schools. Another mistake: Some districts may be spending in a way that’s at odds with what the community values. Lastly, the mother of all mistakes would be spending in a way that doesn’t demonstrate results for students.

Hess: Overall, what share of the spending that you see do you find concerning?

Roza: That’s the $189 billion question, Rick. For starters, only 10 percent of the funding has been spent so far. And any eventual answer to your question is going to come on a district-by-district basis. One district may have spent thoughtfully while the neighboring one may not have much to show for it. That last part is key. Because part of the proof on spending is in the outcomes. What did you get for the spending? We need to think hard about how we’re tracking this and on what basis we’re evaluating what success means for this money, because the feds certainly didn’t define it. But communities sure can press their districts on this.

Hess: You spend a lot of time talking to state, system, and school leaders. When you do, what kind of advice are you giving them?

Roza: I don’t think it’s about what specifically to buy because districts and schools are different. But we did outline some principles to guide those choices and drafted questions to hopefully prompt wise spending. We suggest avoiding recurring commitments, spending equitably, and measuring whether investments are working. We’ve encouraged districts to keep the focus on students and avoid one-size-fits-all solutions. Toward that end, we’ve seen some districts, like Atlanta, Chicago, and Denver, send a portion of the money directly to schools so principals and communities can work together on what their students need. Many, including us, were hoping that a federal education package of this size would spur some lasting innovations. So far, many districts are doing more of the same things they’ve always done. But a few states, like Utah, are deploying a slice of funds via competitive grants for new ways to serve students. And some districts are making bold moves, such as allowing drivers to bring their toddlers on their bus routes or offering parents cash incentives to arrange their own transportation in response to the school bus driver shortage.

Hess: How well do you think the media is covering the use of these funds? Pretty well? Not so well?

Roza: This is an important moment for ed-finance journalism. Most districts have more funds than they’ve ever had. But some in the media are having a hard time shifting their coverage to meet this new reality. I think media got used to a certain narrative, one of scarcity and cuts in public education. And the media story that “teachers are leaving in droves” keeps popping up even though the numbers say otherwise—job openings are indeed everywhere, but so far, those appear to be driven more by a surge in new hiring funded by relief dollars than by teacher departures. There’s so much for journalists to cover right now: how districts are investing new dollars; whether that’s working to meet student needs; what that means for the labor market. The public needs media to meet this moment.

Hess: What should readers know about federal Covid aid that may surprise them?

Roza: The money is so flexible, and if districts are saying they’re not allowed to do something, they’re usually wrong. We’ve heard districts cite all sorts of restrictions that just don’t exist. For instance, some say they aren’t allowed to give any of the money to families, and that’s simply not true. There are districts right now sending a portion of the dollars to families for all sorts of things, like to parents for getting their kids to school, or to high schoolers for attendance in various programs or for getting vaccinated, or to families to pay for enrichment programs of their choosing or college savings accounts, and so on.

Hess: OK, last question. Any advice for parents, educators, or local officials who want to help ensure this money gets spent wisely and well?

Roza: While the feds attached very few strings to this money, one significant string is the requirement that districts engage with their communities when making spending decisions. This means that for the first time ever, parents can have a real voice when it comes to these decisions. And their voice has the backing of federal law. Hopefully, the added participation in financial choices can help keep the focus on students. Otherwise, it’s easy for budgets to be driven by a few strong political players or focus more heavily on employee impacts and potentially lose sight of what all the spending is about, really, which is the kids. There’s a real opportunity with this engagement to rebalance the school budgeting process. And that would be a win for districts as it has the potential to build community trust, ideas, and buy-in.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Frederick Hess is director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute and an executive editor of Education Next.

This post originally appeared on Rick Hess Straight Up.

The post Ed Finance Guru Marguerite Roza on How Schools Can Best Spend Covid Aid appeared first on Education Next.

[NDN/ccn/comedia Links]

News…. browse around here

College admissions easily capture the public’s interest, and rising rates of high-school graduation and postsecondary enrollment are typically met with applause. But what matters most is whether students who go to college actually get a degree. And at least one third of all U.S. students don’t, even six years after they enroll.

College admissions easily capture the public’s interest, and rising rates of high-school graduation and postsecondary enrollment are typically met with applause. But what matters most is whether students who go to college actually get a degree. And at least one third of all U.S. students don’t, even six years after they enroll.

This “college completion crisis” has inspired a range of responses, including President Biden’s proposed $6.2 billion Completion Grant Program currently before Congress. But what is the exact nature of completion challenge? Earlier research focusing on trends through 1990 found broad declines in college graduation rates, especially among men attending less-selective four-year schools. Since then, however, the picture of college enrollment has changed dramatically, with increases in both high-school graduation and college matriculation rates. Have completion rates changed as well?

To find out, we analyze federal education and Census data and find that rates of college completion have gone up since 1990, at a broad mix of institution types and among both men and women. In looking at two federal longitudinal studies, we find students who were slated to graduate high school in 2004 are 3.8 percentage points more likely to graduate college than students from the class of 1992. This trend is confirmed in federal data, the Census, and registrar data from 10 public universities.

What’s driving this growth? We look at student background and academic preparation, as well as institutional practices like support-service spending, and find that none of these potential factors explain the changes. But one trend is clear across all the datasets: compared to decades past, college students have been earning better grades in recent years, and better college grades are strongly associated with higher rates of graduation. We explore a range of factors that could influence student performance, such as high-school preparation and rates of labor-force participation in college, and find that these would predict students to be less likely to graduate, not more.

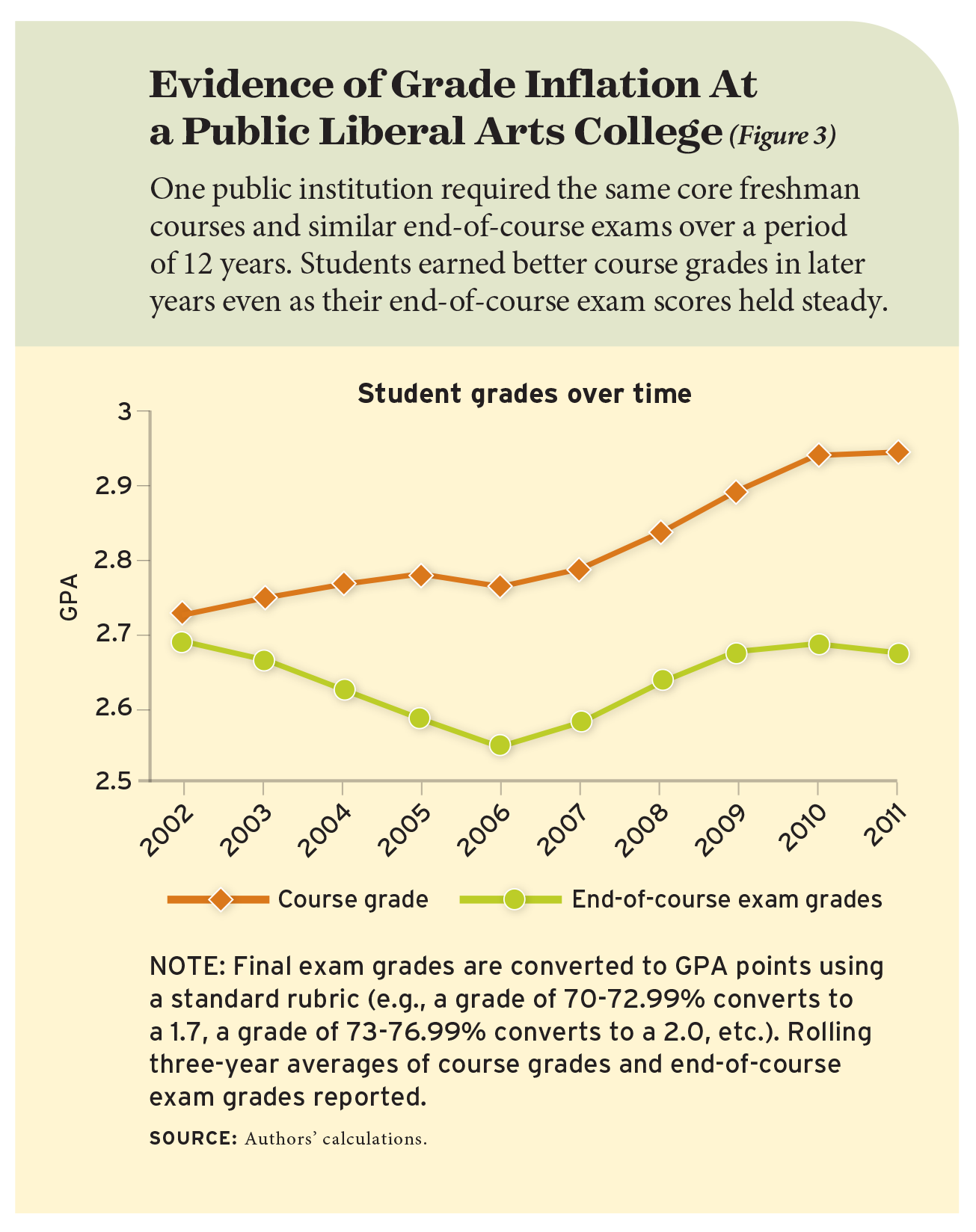

To investigate the possibility of college grade inflation, we find an ideal test at a public liberal arts college that required the same core courses and nearly identical end-of-course exams over a period of 12 years. In looking at student grades, exam scores, and graduate rates from 2001 to 2012, we find evidence of more lax standards in grading. In looking at the end-of-course exams, we see that in those classes, students earned better grades in later years even as their exam scores held steady. In two required science courses that gave the same tests over time, even as students’ grades were going up, their performance on nearly identical exams stayed about the same. Meanwhile, the school’s graduation rate grew to 85.9 percent from 83.1 percent during that time, and students’ grade-point averages increased to 3.02 from 2.77.

While earning a degree is something to be lauded, evidence of grade inflation raises important questions about the meaning of some college degrees. And with growing uncertainty about the relative return on investment in terms of both time and tuition, both students and institutions should take a hard look at the ultimate value of their efforts.

Gains in Graduation

We first establish that college graduation rates have increased since 1990 based on three sources of nationwide data. First, U.S. Census data show growth in the share of 25-year-olds who have earned bachelor’s degrees out of all 25-year-olds with at least some college education, to 46 percent in 2010 from 39 percent in 1990. This increase is especially large for women, to 49 percent in 2010 from 39 percent in 1990.

Second, we calculate changes in the rates of college graduation within eight years of students’ expected high-school graduation date based on two datasets from the National Center for Education Statistics: the National Education Longitudinal Study of 1988, which followed a representative sample of students who were in 8th grade in 1988 through high school, college, and early adulthood, and the Education Longitudinal Study of 2002, which did the same for a representative sample of students who were in 10th grade in 2002. Both studies collect detailed data about student and family backgrounds, academic performance in high school, and postsecondary education. They cease data collection eight years after the expected date of high-school graduation.

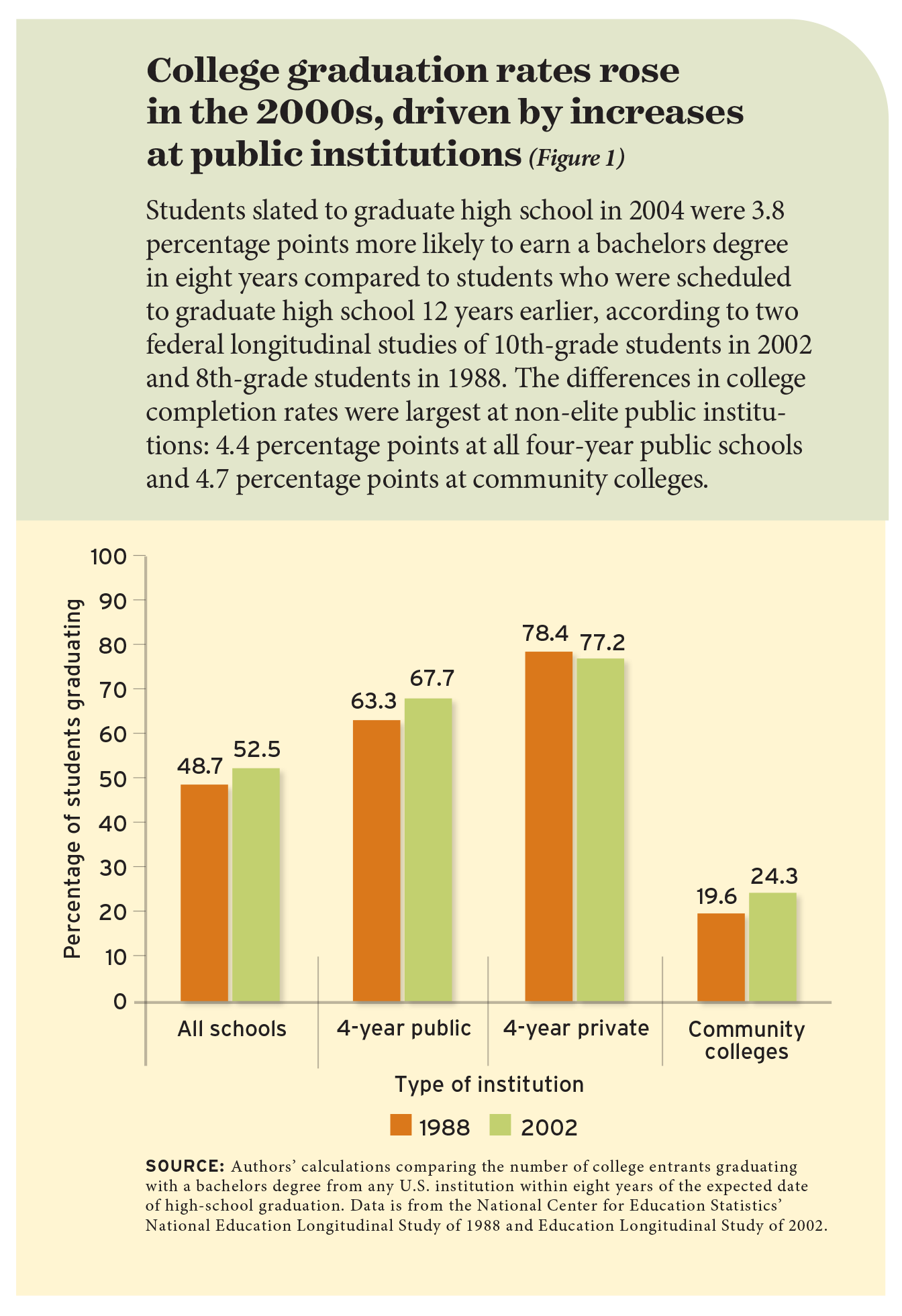

These federal data show that the share of college entrants graduating from any U.S. institution within eight years of high-school graduation increased by 3.8 percentage points between the 1988 and 2002 study sample groups, to 52.5 percent from 48.7 percent (see Figure 1). Among students attending the 50 top-ranked four-year public schools, identified based on 2005 rankings by U.S. News and World Report, the eight-year graduation rate increased to 90.7 percent of students from the 2002 group compared to 82.1 percent of the 1988 group. Among students attending public four-year schools not in the top 50, the eight-year graduation rate was 61 percent for the 2002 group compared to 56.1 percent for the 1988 group.

Third, we also look at the federal Integrated Post-secondary Education Data System, which shows six-year graduation rates for first-time, full-time students that match the trends in our other data sources. We consider data from 1990 to 2010 and look at graduation rates by institution type, including public (top 50 and non-top 50), nonprofit (highly selective and non-selective), and for-profit schools. The highest rates are for institutions with more competitive admissions standards: highly selective nonprofit universities and top-50 public schools. The lowest rate is for for-profit institutions, which experienced rapid growth in enrollment and declines in graduation rates. By contrast, the overall rates for all public and nonprofit institutions continuously increase from 1991 to 2010, with a combined, enrollment-weighted rate of 59.7 percent in 2010 compared to 52.0 percent in 1990.

What’s Driving Graduation Growth?

What accounts for this growth? Did students change, or was something on campus different?

Perhaps changes in enrollment are driving rates up. But in looking at our main samples, we see that college enrollment increased to 78.3 percent of the 2002 group from 69.3 percent of the 1988 group. Federal enrollment data from the Digest of Education Statistics show that enrollment has grown steadily since 1975 and that, at least since the 1990s, it has increased at every type of institution. With a larger fraction of students entering college, more students likely come from farther down the distribution of student achievement. Therefore, enrollment trends are unlikely to explain increases in graduation rates.

Perhaps students are, on the whole, more prepared for college than in the past. But performance of 17-year-old students in the United States on the math and reading portions of National Assessment of Educational Progress has been essentially unchanged since the 1970s. Using this information, we can make a measure of math test scores that are comparable over time. In the longitudinal surveys, we find that students from the 2002 group who earned college degrees within eight years had worse math performance in high school compared to their counterparts from the 1988 study. The average math test score percentile of college enrollees fell to 55.9 from 58.9. In these samples, student preparedness would predict a decline in graduation rates of 1.26 percentage points—not an increase.

Perhaps students are working harder at school. But prior research doesn’t show that. A study by Philip S. Babcock and Mindy Marks found that, while full-time college students spent 40 hours a week on their studies in the 1960s, they spent just 27 hours a week on schoolwork by 2003. Other research has found students are spending more time on paid labor while in college. For example, a study by Judith Scott-Clayton found that the average labor supply among full-time college students ages 18 to 22 grew to 11 hours per week in 2000 compared to 6 hours in 1970.

We investigate other potential factors, such as changes in the types of institutions students attend, college affordability, and instructional and other campus resources, as potential contributors to graduation-rate patterns. Enrollment growth was concentrated at non-elite institutions, even as inflation-adjusted tuition and fees increased by more than 300 percent since 1987. Meanwhile, the student-to-faculty ratios at colleges attended by the students in the 2002 and 1988 surveys were nearly the same, at 40.4 for the 2002 group compared to 39.4 for the 1988 group, while mean instructional expenditures per student fell somewhat to $4,288 from $4,581.

These trends would all predict decreases in graduation rates, not growth. In fact, in our analysis of the impact on student and institutional factors influencing likelihood of graduation, we find that students from the 2002 group are predicted to be 1.92 percentage points less likely to graduate than students from the 1988 group. But those students, in reality, graduated in greater numbers—they were 3.8 percentage points more likely to graduate than the 1988 group and 5.7 percentage points more likely to graduate than the predictive factors in our analysis would suggest.

We turn our attention to one trend that is associated with higher rates of degree attainment that is not yet accounted for in this analysis. The longitudinal surveys also tracked students’ grades once they were enrolled in college, and they show that students from the later sample earned better grades than their older forebearers. In the 2002 group, students had an average first-year college GPA of 2.65, while in the 1988 group, students had an average first-year college GPA of 2.44. What changed?

Investigating Grade Inflation

To explain the role of rising GPAs in increasing graduation rates, we incorporate two additional data sets into our review. We then explore the extent to which college GPA predicts graduation, how much GPAs have increased over the time frame considered, and whether that growth is well explained by observable student characteristics, course-taking behavior, or performance on end-of-course exams that have a constant level of difficulty over time.

Data: We look at four data sources. In addition to the longitudinal surveys from 1988 and 2002, we consider data from a group of nine large public universities for students who first enrolled between 1990 and 2000, as well as detailed student data from a public liberal arts college whose unique course requirements enable us to test our theory of grade inflation.

First, we look at student data from a group of nine large public universities from the Multiple-Institution Database for Investigating Engineering Longitudinal Development, known as the MIDFIELD database. This includes detailed information about 530,036 degree-seeking undergraduate students who started school between 1990 and 2000 at nine institutions: Clemson, the University of Colorado, Colorado State, the University of Florida, Florida State, Georgia Tech, North Carolina State, Purdue, and Virginia Tech. These data include demographics, SAT scores, individual course grades, and degrees earned, and the sample is similar to those in the longitudinal surveys in terms of math quartile, race, and gender. First-year GPA for students at these schools increases to 2.79 from 2.68 over the decade.

The other data set is from a public liberal arts college, which we do not identify. This college has required students take a set of core classes that include final exams that do not differ substantially over time. We review detailed data for the 14,193 students who entered the institution between 2001 and 2012, including demographics, graduation rates, individual course grades, and student scores on the final exam. While these students are unique in some ways, they have a similar distribution of race and ethnicity as those in the other samples, and we see similar trends in GPAs and graduation rates over time. Students’ GPAs increase to 3.02 in 2012 from 2.77 in 2001, and graduation rates grow to 85.9 percent from 83.1 percent.

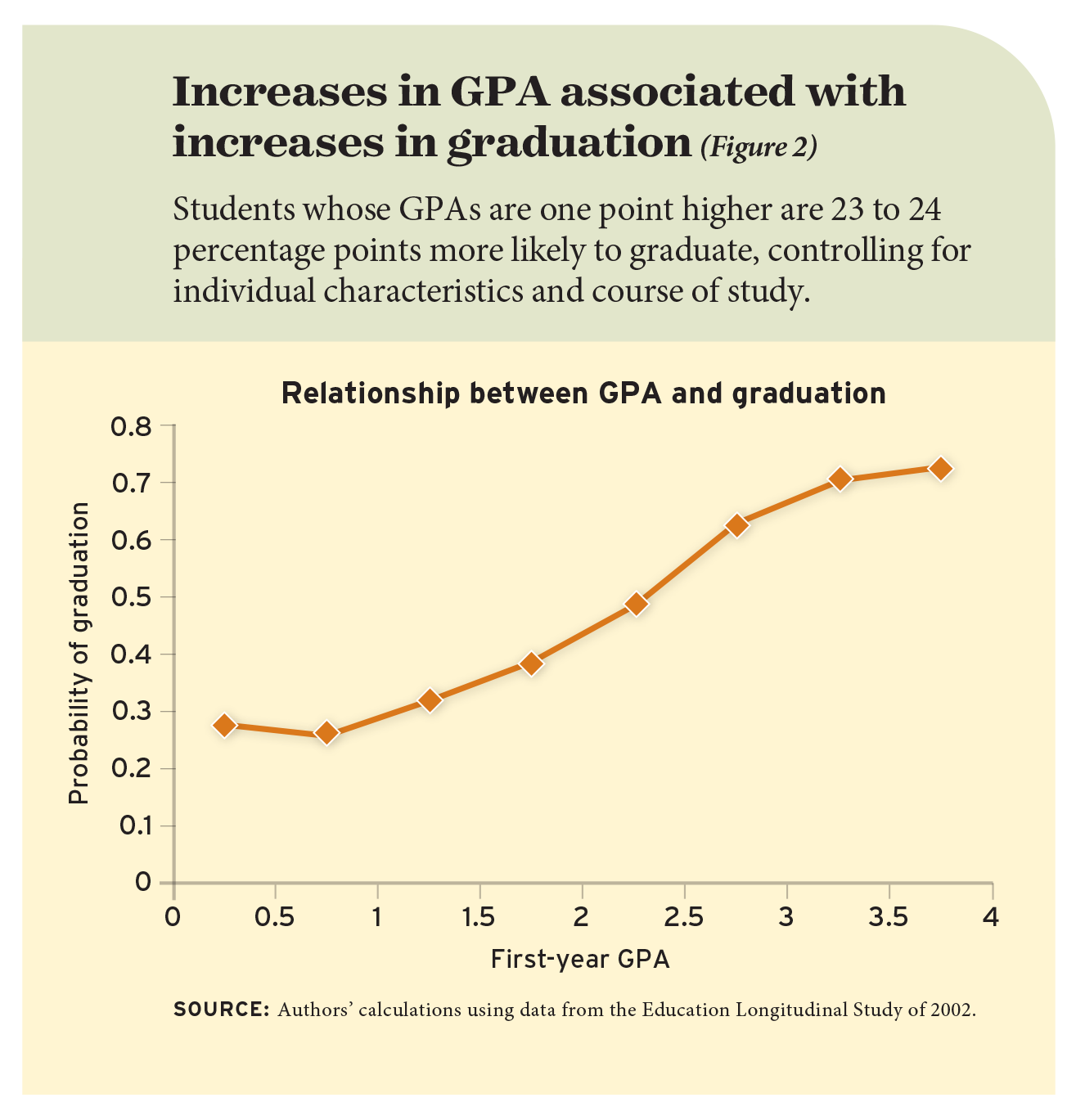

Trends in GPAs and graduation: We look at all four datasets and see that first-year college grades are always predictive of graduation. In both the 1988 and 2002 nationwide samples, a one-point increase in GPA is associated with an increase of about 22 to 24 percentage points in a student’s probability of graduation when controlling for student characteristics and the graduation rate of a student’s selected major (see Figure 2). In looking at the two additional datasets—the group of large public universities and the public liberals arts college—we find an increase of one point in a student’s GPA is associated with an increase of 16 to 21 percentage points in the likelihood of graduation.

We then look at the relationship between GPA and rates of graduation along the grade distribution spectrum and find the biggest differences are between students with D averages and those with C averages. This is likely for two reasons. First, students generally must maintain a GPA above a certain threshold to avoid dismissal. Second, GPA can act as a signal about a student’s ability to succeed in school. In either case, students with higher GPAs are more likely to graduate.

The data show that GPAs increased at all school types. In looking at the 1988 and 2002 samples, we see that 11 percent more first-year college students have a GPA above a 2.0 in the 2002 sample compared to the 1988 sample. This is notable because rules at many institutions require students to maintain GPAs of at least 2.0 in order to remain in good standing. We then look for differences between these samples in student characteristics, to see whether they change over time in ways that would predict increases in average GPA. This includes math scores, race, gender, and parents’ level of education and income—none of which change the effect of GPA substantively.

At the group of nine public universities, during the period we study we see that entering one year later is associated with an increase of 0.019 in first-year GPA. We also look for differences in student characteristics that could predict these increases, using a more detailed set of data that includes demographics as well as students’ SAT scores, home zip codes, transfer status, U.S. citizenship, and courses taken. We control for these factors and find that they explain only about a quarter of the estimated increase. Even the set of courses students choose to take in their first semester on campus does not explain the changes in first-year GPA.

A Real-World Test

The ideal test for whether rising grades can be explained by student preparation, effort, or learning would be a comprehensive assessment that had a constant level of difficulty that was given to students over a period of several years to measure learning in multiple courses. Then, we could see if the grades of students who scored the same on the assessment were increasing, decreasing, or staying the same over time.

We can, in fact, test our hypothesis thanks to a unique aspect of the educational program offered at the public liberal arts college we include in this review. The college requires students to take a number of standard courses that include end-of-course exams, which are either identical over time or have maintained a steady degree

of difficulty.

First, we look at students’ year of entry and average first-year course grades. We find that starting school a year later corresponds to a statistically significant increase of 0.025 grade points, and that this difference holds steady even when we control for students’ scores on end-of-course exams, the specific courses they take, and student characteristics including SAT test scores. This is true even when we consider only core courses required of all freshman students, suggesting that broad changes in the courses students take, characteristics of students, and overall learning as measured by final-exam performance are unlikely to explain improving GPAs over time.

However, it’s possible that the tests themselves have changed, so we look for courses where the exams have remained identical over time. We find two required freshman science classes where the final exams are comprehensive and are graded by machine or in teams. We then examined every version of that test, question by question, from 2001 to 2012 and found that 9 out of 12 were identical to an exam given in another year. This allows for a very close approximation of the ideal test for grade inflation. In looking at results on those tests, controlling for demographics and exam and course fixed effects, we find that entering school one year later corresponds to a large and statistically significant increase of 0.053 grade points (see Figure 3).

In other words, students with the exact same score on the exact same final exam earned better grades in later years. Given the close relationship between GPA and graduation, our finding that grades are increasing over time, even when student characteristics and performance on identical comprehensive final exams are accounted for, suggests that it’s getting easier to earn a degree at the public liberal arts college we study. And, given the similar trends we see between this one school and the nationwide samples from 1988 and 2002, we believe that this discovery is likely informative of broader trends.

How High Is Too High?

Our analysis finds that graduation rates among college students have increased since 1990 and that students are also earning higher grades. The increase in grade-point averages can explain much of the increase in graduation rates. And, in looking at reasons why students are earning higher grades, we present evidence that this increase is not explained by observable student or institution characteristics. Combined with existing work on trends in student study, college preparation, labor supply, the price of college, and resources per student, our evidence suggests that grade inflation is contributing to increasing grades and graduation rates.

Why did grade point averages increase from the 1990s to 2010? It is hard to know for sure. Instructors, departments, and institutions may have incentives to inflate grades or increase GPAs for reasons other than student performance. Instructors who give students higher grades receive better teaching evaluations and high-grading departments typically tend to have larger enrollments—one study found that when average grades were capped at B+ in high-grading departments at Wellesley College, for example, enrollments and professors’ ratings declined.

The recent policy focus on college completion rates seems a likely contributor to increases in average GPAs. As schools and departments face increased scrutiny and, in some cases, increased funding incentives, they may respond by increasing graduation rates. Changing standards of degree receipt is a low-cost way to increase graduation rates. And in fact, graduation rates increased sharply at public four-year schools and community colleges, which rely on tax dollars and can be affected by states’ performance-based funding rules.

Our findings may have important implications for efforts to calculate the returns on investment for a college degree. If institutions are lowering their standards for awarding a degree, as indicated by rising college grades, this could lead to a decline in the college wage premium. As with many policy levers, grade inflation has costs and benefits. We show that it led to an increase in college graduation rates. However, there may be deleterious effects of grade inflation if it changes what is learned in college. Our work highlights the importance of thinking of grading policy as a key decision that colleges make.

Jeffrey T. Denning is associate professor at Brigham Young University, where Eric R. Eide is professor and Richard W. Patterson is assistant professor. Kevin J. Mumford is associate professor and Kozuch director of the Purdue University Research Center in Education. Merrill Warnick is a graduate student at Stanford University.

The post Lower Bars, Higher College GPAs appeared first on Education Next.

[NDN/ccn/comedia Links]

News…. browse around here

A junior economist and doctoral student at the Ifo Center for the Economics of Education, Benjamin Arold, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss Arold’s research, which looks at the impact of the Common Core on subjects outside of math and reading.

A junior economist and doctoral student at the Ifo Center for the Economics of Education, Benjamin Arold, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss Arold’s research, which looks at the impact of the Common Core on subjects outside of math and reading.

The paper, “The Unintended Effects of the Common Core State Standards on Non-Targeted Subjects,” by Arold and M. Danish Shakeel, is available now.

Follow The Education Exchange on Soundcloud, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Stitcher or here on Education Next.

— Education Next

The post The Education Exchange: Common Core Adoption Hurt Student Performance in Science, Social Studies, a New Study Finds appeared first on Education Next.

By: Education Next

Title: The Education Exchange: Common Core Adoption Hurt Student Performance in Science, Social Studies, a New Study Finds

Sourced From: www.educationnext.org/the-education-exchange-common-core-adoption-hurt-student-performance-in-science-social-studies-a-new-study-finds/

Published Date: Mon, 08 Nov 2021 10:00:46 +0000

News…. browse around here