Our annual look back at the year’s most popular Education Next articles is itself a popular article with readers. It’s useful as an indicator of what issues are at the top of the education policy conversation.

When we crafted the introduction to this list a year ago, for the top articles of 2020, we observed, “This year, as our list indicates, race and the Covid-19 pandemic dominated the discussion.” Since then, a new president has been inaugurated, but our list signals that the public hasn’t entirely turned the page: both the pandemic and race-related issues attracted high reader interest in 2021, just as they did the year before.

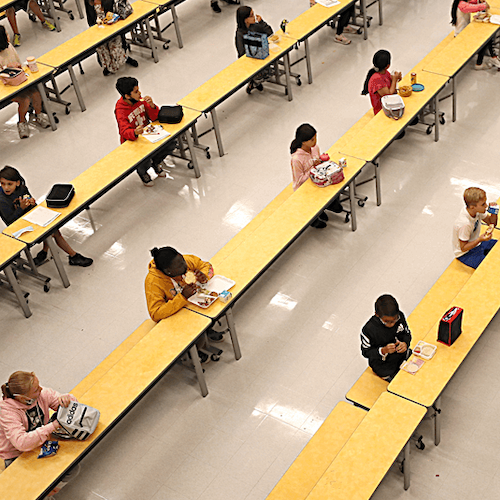

Several articles directly or indirectly related to the pandemic and its effect made the top-20 list. The no. 1 article, “Pandemic Parent Survey Finds Perverse Pattern: Students Are More Likely to Be Attending School in Person Where Covid Is Spreading More Rapidly,” by Michael B. Henderson, Paul E. Peterson, and Martin R. West, reported on what the article called “a troubling pattern: students are most likely to be attending school fully in person in school districts where the virus is spreading most rapidly.” The article explained “To be clear, this pattern does not constitute evidence that greater use of in-person instruction has contributed to the spread of the virus across the United States. It is equally plausible that counties where in-person schooling is most common are places where there are fewer measures and practices in the wider community designed to mitigate Covid spread.”

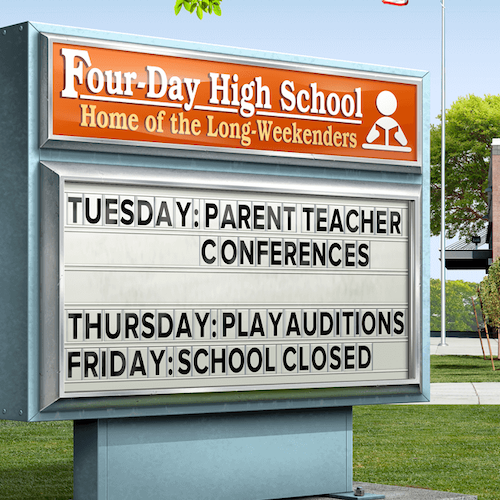

Other articles whose findings related to the pandemic or had implications for education amid or after the pandemic included “A Test for the Test-Makers,” “The Shrinking School Week,” “The Covid-19 Pandemic Is a Lousy Natural Experiment for Studying the Effects of Online Learning” “The Politics of Closing Schools,” “Addressing Significant Learning Loss in Mathematics During Covid-19 and Beyond,” and “Move To Trash: Five pandemic-era education practices that deserve to be dumped in the dustbin.”

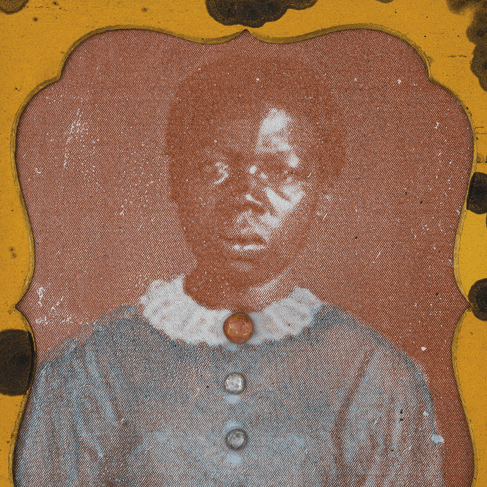

Articles about race-related education issues also did well with readers. “Critical Race Theory Collides with the Law,” “Teaching About Slavery,” “Ethnic Studies in California,” and “Segregation and Racial Gaps in Special Education” all dealt with those topics.

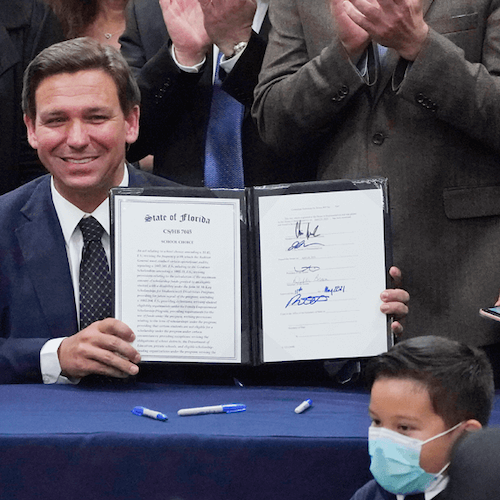

Perhaps the conflicts over pandemic policies and Critical Race Theory helped provide a push for school choice. Choice—whether in the form of vouchers, scholarships, or charter schools—was the subject of several other articles that made the top 20 list, including “School Choice Advances in the States,” “School Choice and the ‘Truly Disadvantaged,’” “What’s Next in New Orleans,” and “Betsy DeVos and the Future of Education Reform.”

Who knows what 2022 will bring? We hope for our readers the year ahead is one of good health and of continued learning. We look forward to a time when pandemic-related articles no longer dominate our list.

The full Top 20 Education Next articles of 2020 list follows:

1. Pandemic Parent Survey Finds Perverse Pattern: Students Are More Likely to Be Attending School in Person Where Covid Is Spreading More Rapidly

Majority of students receiving fully remote instruction; Private-school students more likely to be in person full time

By Michael B. Henderson, Paul E. Peterson, and Martin R. West

2. Critical Race Theory Collides with the Law

Can a school require students to “confess their privilege” in class?

By Joshua Dunn

3. Teaching about Slavery

“Asking how to teach about slavery is a little like asking why we teach at all”

By Danielle Allen, Daina Ramey Berry, David W. Blight, Allen C. Guelzo, Robert Maranto, Ian V. Rowe, and Adrienne Stang

4. Ethnic Studies in California

An unsteady jump from college campuses to K-12 classrooms

By Miriam Pawel

5. Segregation and Racial Gaps in Special Education

New evidence on the debate over disproportionality

By Todd E. Elder, David Figlio, Scott Imberman, and Claudia Persico

6. Making Education Research Relevant

How researchers can give teachers more choices

By Daniel T. Willingham and David B. Daniel

7. Proving the School-to-Prison Pipeline

Stricter middle schools raise the risk of adult arrests

By Andrew Bacher-Hicks, Stephen B. Billings, and David J. Deming

8. What I Learned in 23 Years Ranking America’s Most Challenging High Schools

Most students are capable of much more learning than they are asked to do

By Jay Mathews

9. A Test for the Test Makers

College Board and ACT move to grow and diversify as the pandemic fuels test-optional admissions trend

By Jon Marcus

10. Addressing Significant Learning Loss in Mathematics During Covid-19 and Beyond

The pandemic has amplified existing skill gaps, but new strategies and new tech could help

By Joel Rose

11. The Shrinking School Week

Effects of a four-day schedule on student achievement

By Paul N. Thompson

12. Computer Science for All?

As a new subject spreads, debates flare about precisely what is taught, to whom, and for what purpose

By Jennifer Oldham

13. The Covid-19 Pandemic Is a Lousy Natural Experiment for Studying the Effects of Online Learning

Focus, instead, on measuring the overall effects of the pandemic itself

By Andrew Bacher-Hicks and Joshua Goodman

14. School Choice Advances in the States

Advocates describe “breakthrough year”

By Alan Greenblatt

15. The Politics of Closing Schools

Teachers unions and the Covid-19 pandemic in Europe

By Susanne Wiborg

16. Move to Trash

Five pandemic-era education practices that deserve to be dumped in the dustbin

By Michael J. Petrilli

17. School Choice and “The Truly Disadvantaged”

Vouchers boost college going, but not for students in greatest need

By Albert Cheng and Paul E. Peterson

18. The Orchid and the Dandelion

New research uncovers a link between a genetic variation and how students respond to teaching. The potential implications for schools—and society—are vast.

By Laurence Holt

19. What’s Next in New Orleans

The Louisiana city has the most unusual school system in America. But can the new board of a radically decentralized district handle the latest challenges?

By Danielle Dreilinger

20. Betsy DeVos and the Future of Education Reform

My years as assistant secretary of education gave me a firsthand look at how infighting among education reformers is hampering progress toward change.

By Jim Blew

The post The Top 20 Education Next Articles of 2021 appeared first on Education Next.

By: Education Next

Title: The Top 20 Education Next Articles of 2021

Sourced From: www.educationnext.org/top-20-education-next-articles-2021/

Published Date: Tue, 14 Dec 2021 10:00:11 +0000

News…. browse around here

The Will Skillman Fellow in Education at The Heritage Foundation, Jonathan Butcher, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss the growing controversy over critical race theory and its place in the classroom.

The Will Skillman Fellow in Education at The Heritage Foundation, Jonathan Butcher, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss the growing controversy over critical race theory and its place in the classroom.