How expensive is a college degree? Usually, the answer is based on what students pay in tuition and fees compared to what they earn after graduation. As a result, policymakers often promote enrollment and applaud growth in tech-heavy programs that tend to produce high-earning graduates, like engineering and computer science—especially given the explosive growth in college prices, which have doubled in the past 30 years.

How expensive is a college degree? Usually, the answer is based on what students pay in tuition and fees compared to what they earn after graduation. As a result, policymakers often promote enrollment and applaud growth in tech-heavy programs that tend to produce high-earning graduates, like engineering and computer science—especially given the explosive growth in college prices, which have doubled in the past 30 years.

But that thinking only focuses on one side of the equation: the student’s private return on investment, based on the labor-market value of a degree relative to what the student paid. We know very little about the economic cost of running an electrical engineering program compared to, say, a history department, or the resource consequences of steering more students into these fields.

To fill this gap, we examine department-level data on expenditures, outputs, and factors of production for undergraduate, graduate, and professional degree programs at nearly 600 four-year institutions across the United States from 2000 to 2017. Our analysis compares the instructional costs per student credit hour at more than 8,000 departments in 20 disciplines, including both in-person and online study.

We establish five new facts about college costs. First, we find substantial cost differences across fields of study. On the whole, costs are higher in fields where graduates earn more and in pre-professional programs. Second, most of these patterns can be explained by differences in class size and, to a lesser extent, differences in average faculty pay. However, some fields with highly paid faculty, like economics, offset this with large classes.

Third, cost differences have evolved over time. Programs in some fields, such as mechanical engineering, chemistry, physics, and nursing, have shown steep annual declines in spending, while others like fine and studio arts, history, and political science have grown more expensive each year. Fourth, these trends are explained in part by a growing number of adjunct faculty as well as changes in class size and faculty teaching loads. Fifth, online instruction is not a cost-saver. It is neither more nor less expensive than in-person classes.

Our results underscore the potential wedge between the social and private returns to higher education. That is, the social return to investment in high-earning fields may be lower than wage premiums suggest, because high-return fields also tend to be more costly to teach. This highlights the need for policymakers to consider the cost implications of changes in the mix of fields students study.

In addition, our work suggests that while differences in production technology enable some departments to take different approaches to cost management, from changing the mix of faculty to increasing class size, online instruction does not have a meaningful association with college costs, at least in its current form. Any one-discipline-fits-all approach to addressing cost escalation in higher education, including moving more classes online, is likely to be ineffective.

Cost Drivers on Campus

Scholars have long noted the tendency for college costs to grow faster than the broader economy. Some argue that this is inevitable because postsecondary education is inherently labor-intensive and therefore has not benefitted from the kinds of productivity-enhancing innovations that have driven down costs in other industries. Other potential explanations include the proclivity of colleges to maximize revenue in an effort to compete for prestige, school spending on student amenities, and the expansion of unnecessary administrative positions.

In all cases, programs produce a set of outputs, such as undergraduate instruction or research publications, using a large set of inputs, such as faculty of different types, classrooms, office space, technology, and laboratories. The relationship between these varies across fields of study. Some disciplines require intense interaction between students and faculty to produce a given level of instructional quality—think of a debate-driven course with long extemporaneous papers to grade—while others require laboratory sessions that rely on expensive equipment and supplies. By contrast, other fields of study may be able to take advantage of economies of scale and scope, such as those that deliver “101”-style general-education courses for the entire institution. In addition, departments with undergraduate and graduate programs can tap graduate students to serve as lower-cost instructors. Such differences affect class size, faculty mix, faculty teaching load, and non-personnel expenditures—all of which determine the cost per unit of instruction.

Data and Method

To compare instructional costs by field of study, we use department-level data from 2000 to 2017 from University of Delaware,s Cost Study (also known as the National Study of Instructional Costs and Productivity). Instructional activity is measured by student credit hours, organized class sections, and faculty full-time equivalents. Student credit hours and class sections are disaggregated by instructor type, such as tenure track, supplemental, or teaching assistants, and by course level, such as lower-division undergraduate, upper-division undergraduate, and graduate. Finally, institutions report total direct expenditures for instruction, research, and public service and total undergraduate and graduate student credit hours for the entire academic year.

We work with direct instructional expenditures per student credit hour as our main measure of costs, which include salaries, benefits, and non-personnel expenses. In 2015, the study added a component to the survey to capture information about online instruction. These data contain information on online student credit hours by department at the undergraduate and graduate levels.

Institutional participation in the cost study is voluntary. Therefore, we assess how well our sample matched the broader universe of public and private nonprofit four-year institutions operating in the United States, based on the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. We estimate that our sample represents 23 percent of all degrees awarded between 1998 and 2015, including 32 percent of degrees at public institutions and 8 percent of degrees at private schools.

We focus on data collected from doctoral, master’s, and bachelor’s degree-granting institutions in the United States. Our analysis looks at 20 core fields of study, including the largest fields (collectively accounting for more than half of student credit hours) and fields that are particularly salient for institutional leaders and policymakers. Our final sample contains 43,819 institution-year observations from 8,221 departments in 20 disciplines at 594 institutions. The data for online programs beginning in 2015 include 3,358 unique departments from 20 disciplines at 238 institutions across 3 years.

Using these data, we construct variables that measure costs, outputs, and inputs. Our primary outcome of interest is direct instructional spending per student credit hour, which we construct by dividing annual instructional costs by annual student credit hours at the department level. We also calculate this ratio for the personnel expenditures portion of costs. Finally, to analyze the sources of differences in costs across programs, we calculate average class size based on fall credit hours, faculty per student, and faculty teaching load.

Differences by Degree Program

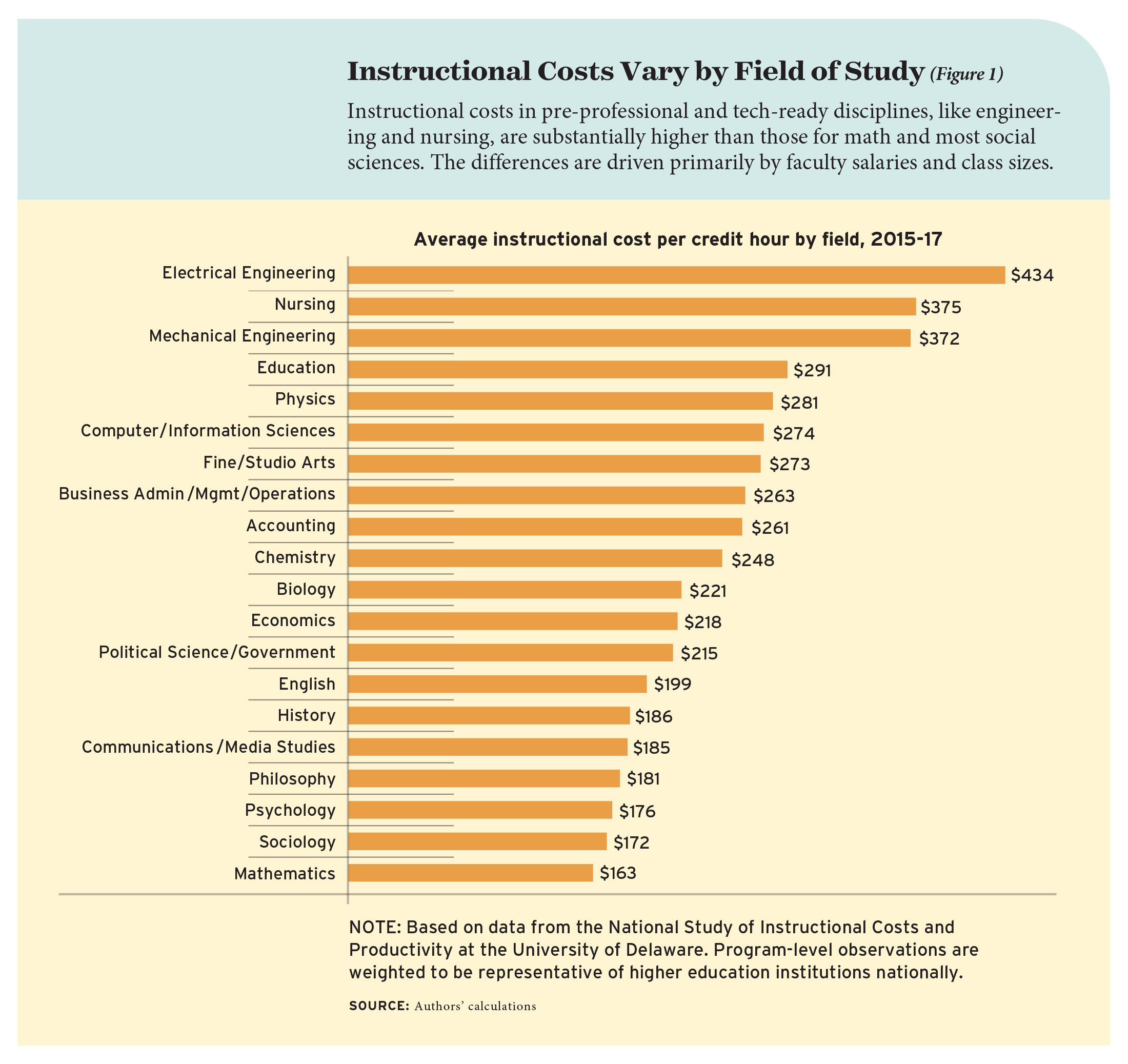

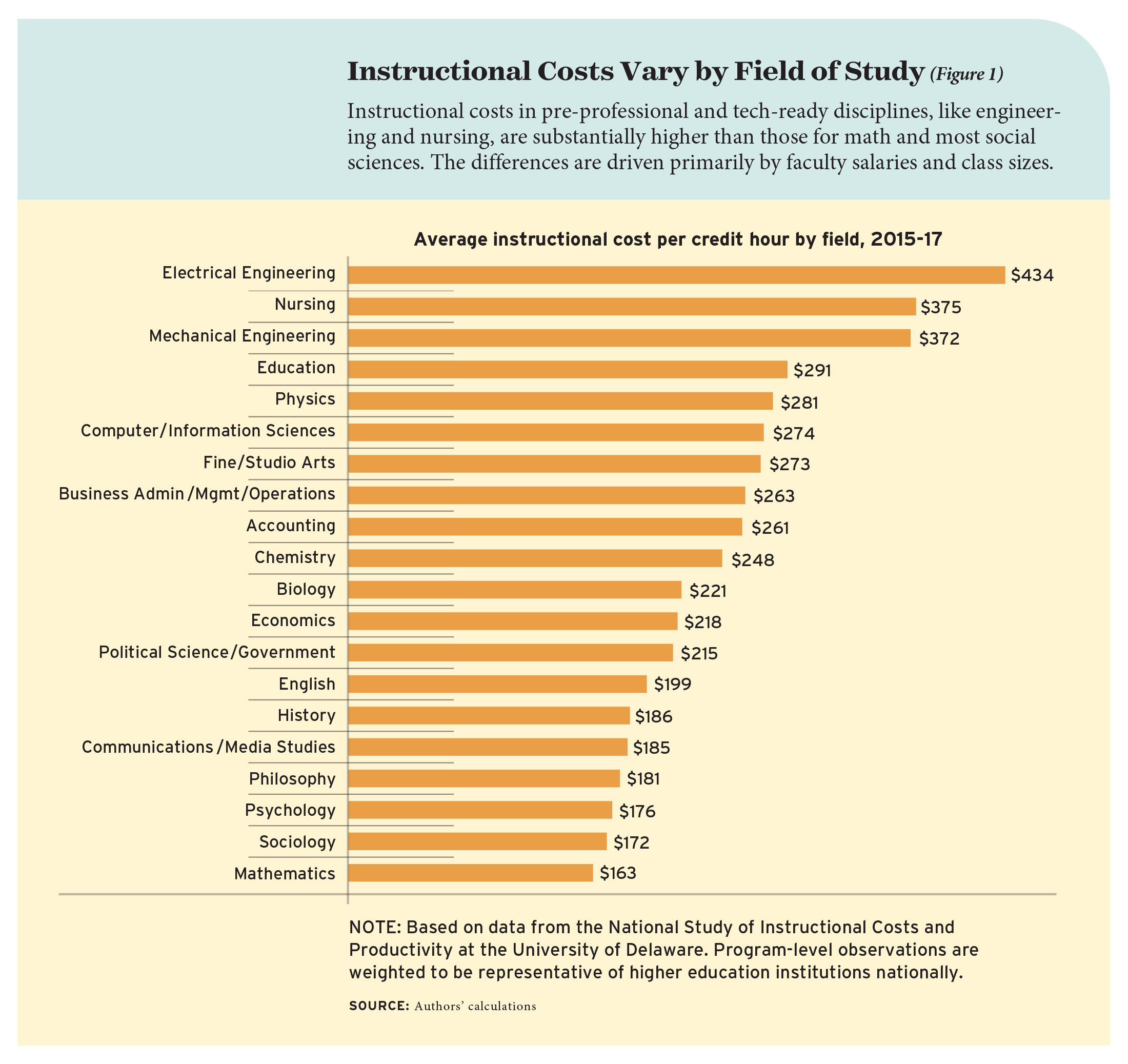

We find substantial variation across disciplines in average costs per student credit hour (see Figure 1). Costs range from about $434 per student credit hour in electrical engineering to $163 per hour in math. Our benchmark department, English, costs $199 per hour; the mean cost across the group of 20 fields is $228. Most social-science disciplines and philosophy are relatively less expensive, while science, technology, and pre-professional programs like nursing are more costly. This broad conclusion holds across all institutions—nursing is a more expensive program to operate at elite private research institutions and less selective public institutions alike.

To compare costs across fields of study, we use the English department as a benchmark and look at costs by discipline from 2015–17. First, we calculate the average direct instructional cost per student credit hour for English at each school. We then calculate the within-institution difference between direct instructional expenditures per student credit hour for each of the other 19 disciplines and the same measure for English. We do this for all institutions and disciplines in our sample and then compute averages for each field of study.

In many cases, we find higher instructional expenses in the fields that also produce higher-earning graduates. For example, at $434 per student credit hour, electrical engineering costs 90 percent more than English. In looking at research by Brad Hershbein and Melissa S. Kearney, we see that adults with electrical engineering degrees have substantially higher average salaries throughout their careers. One year after graduation, electrical engineering majors earn more than double the average salary paid to English majors, or $63,000 compared to $31,000. Some 15 years later, that difference is about 83 percent, or $106,000 compared to $58,000.

There are several exceptions to these overall patterns. Math costs about 25 percent less than English, yet adults with mathematics or statistics degrees still earn more: $45,000 one year after graduation, a difference of 45 percent, and $76,000 in year 16, a difference of 32 percent.

In addition, education and fine and studio arts are among the most costly programs to operate, yet their graduates are also among the lowest paid. Education costs about $291 per credit hour, about 45 percent more than English. But adults with degrees in elementary education earn less than English majors throughout most of their careers—in year 16, they earn $44,000 compared to $58,000, a difference of about 35 percent. Similarly, fine and studio arts instruction costs about $273 per credit hour, but arts majors earn about the same or slightly less than English majors, on average: both graduates earn $31,000 one year after graduation. Some 15 years later, arts majors earn $55,000 versus $58,000 for adults with English degrees.

We also look at the growth in the number of student credit hours in each field during the study period of 2000–2017 and find that, on the whole, enrollment is growing fastest in some of the more costly fields. The highest annual rates of growth are in nursing, at 5.4 percent, and mechanical engineering, at 4.9 percent. Meanwhile, we also see that student credit hours are declining in four fields: English, history, education, and fine and studio arts. If those higher costs were associated with challenges in dynamically adjusting inputs, such as instructors and course sections, we would expect that fast-growing fields would have lower costs than slow-growing or declining ones. In fact we see the opposite.

More costly fields also are more likely to have access to additional revenue sources than English departments. Almost all of the most expensive fields are typically housed in separate schools from English, such as colleges of engineering, business, and education. This permits them to generate additional revenue through differential tuition bills or fees, and through separate fundraising efforts from alumni or industry. In some cases, these fields also have access to dedicated state appropriations for instructional costs. For example, in Texas and North Carolina, programs in the sciences, engineering, and nursing are eligible for more public support than programs in the liberal arts and social sciences.

Variety in Cost Contributors Across Fields of Study

We next investigate the factors behind these cost differences, looking at faculty salaries, class sizes, faculty workload—defined as the number of organized class sections divided by the number of full-time equivalent faculty—and non-personnel costs like equipment and supplies.

Instructional cost differences across fields can mostly be explained by large differences in class size across disciplines and, to a lesser extent, differences in average faculty pay. Teaching loads and other non-personnel expenditures explain relatively little.

Instructional Style

Although each field is slightly different, a few general patterns emerge. Economics, political science, accounting, and business have high faculty salaries that are mostly offset by large classes. Engineering and nursing are more expensive than English as a result of higher faculty salaries and lower teaching loads without commensurately larger classes. Workload and non-personnel expenses are important for some of the sciences with laboratory components—namely, biology and chemistry—but otherwise explain relatively little of the observed cost differences.

Consider economics, which is approximately 8 percent less expensive than English. Economics faculty are more highly paid than English professors. Postsecondary English instructors earn about 54 percent less than economics professors, with mean annual wages of $80,340 a year compared to $123,720. Thus if all cost drivers other than average pay were equalized between the two fields, economics would be more expensive. On the other hand, economics classes tend to be much larger than English classes, so class-size differences would make economics instruction less expensive. The faculty workload is a little lighter in economics than in English, so if that were the only driver of cost differences, economics would be about 3 percent more expensive.

Putting these findings together, we see that economics departments are able to field classes that are large enough to more than offset the higher salary and slightly lower workload of economics faculty, resulting in slightly lower average costs than English. Yet economics graduates earn substantially more: one year after graduation, the average salary is $48,000, or about 55 percent more than English majors. Fifteen years later, that difference grows to about 83 percent, or $106,000 for economics majors compared to $58,000 for adults with English degrees.

Mechanical engineering, a fast-growing field that is 62 percent more expensive than English, provides a counterexample. Engineering instructors have mean annual wages of $114,130, about 43 percent more than English instructors, as well as lower teaching loads than English faculty. As a result, the average difference in faculty pay across these two fields contributes substantially to the overall cost difference. Unlike economics, however, classes are only modestly larger in mechanical engineering than in English. Class-size differences are not large enough to offset the higher salary and lower teaching load, and thus mechanical engineering remains much more expensive than English. Research shows wide differences in earnings for mechanical engineering graduates compared to adults with English degrees: $60,000 one year after graduation, a difference of about 95 percent, and $104,000 some 15 years later, a difference of about 80 percent.

Faculty Type and Class Size

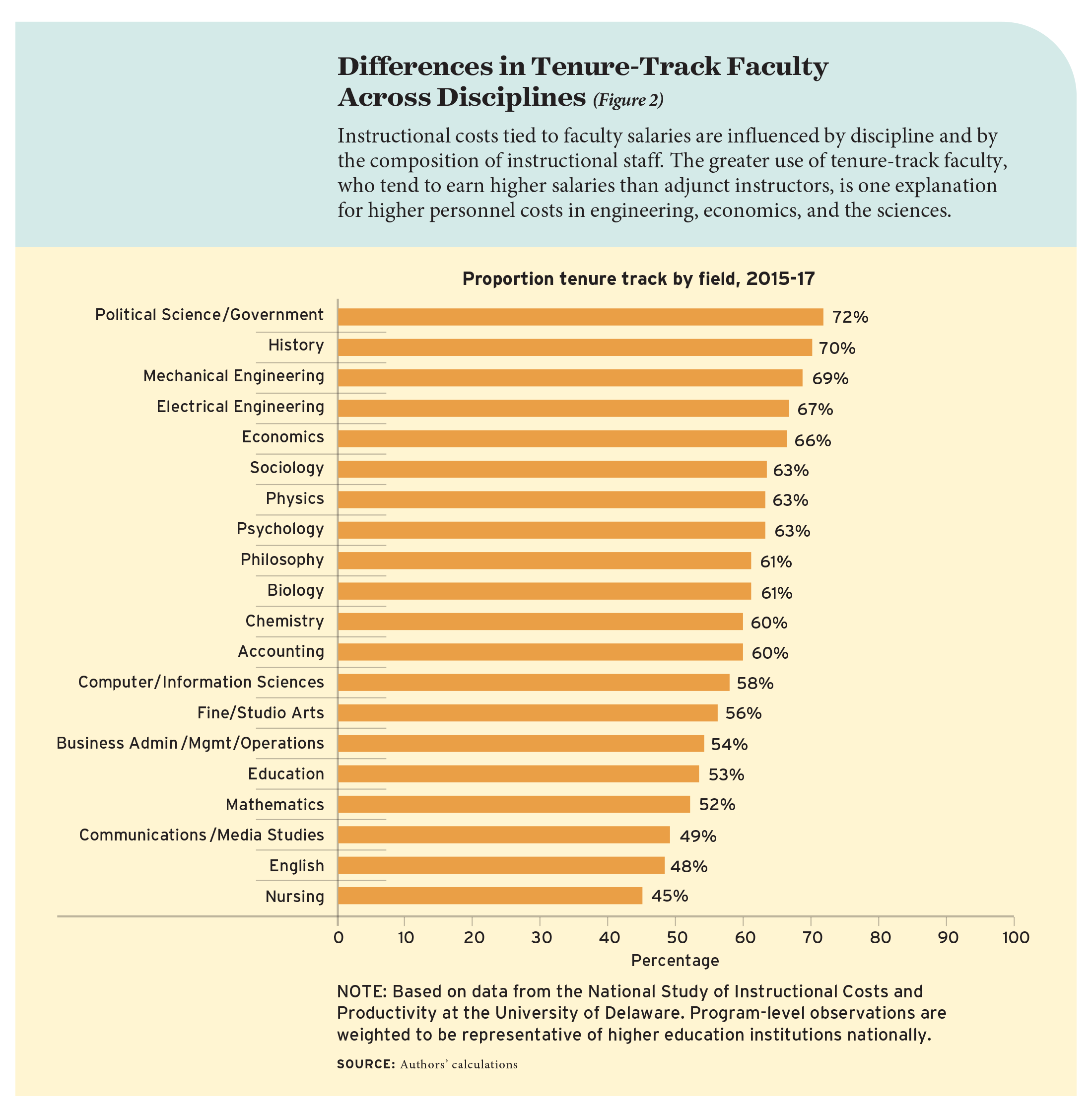

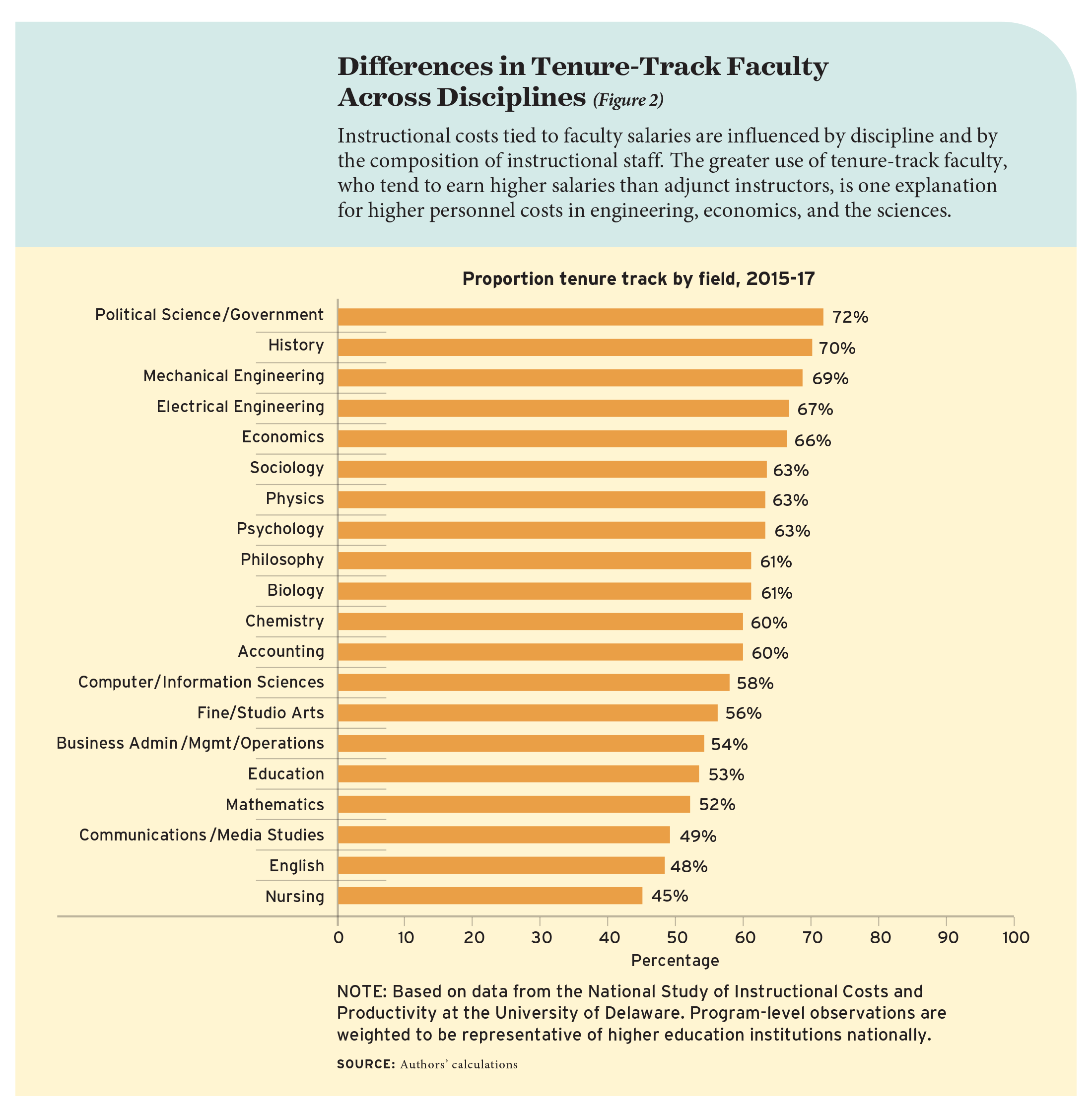

A department’s faculty salaries are driven by the mix of tenure-track and adjunct instructors as well as the salary for that particular discipline. We find quite a bit of variation in the share of tenure-track faculty by field (see Figure 2). In nursing, nearly 60 percent of instructors are not on the tenure track, while in mechanical and electrical engineering, three quarters of faculty are in tenure-track roles. English, communications, and math also have relatively low shares of tenure-track faculty. Thus, greater use of tenure-track faculty, which is more expensive, is one explanation for higher personnel costs in engineering, economics, and the sciences. Across the board, we see declines in the share of tenure-track faculty during the study period, with departments relying more on lower-cost adjunct instructors.

The second key cost driver, beyond faculty salaries, is class size. Differences in class size are a function of the mix of course types offered, such as lower-level undergraduate, upper-level undergraduate, and graduate, as well as the average class size for those courses. Lower-level classes tend to be larger and therefore less costly, whereas upper-level and graduate courses have smaller class sizes and are therefore more expensive.

We find substantial differences in the mix of course types offered, with relatively fewer lower-division courses in professional fields like education and business, and many lower-division courses in mathematics and science disciplines like physics and chemistry. Fields with relatively little undergraduate instruction, like engineering and nursing, tend to be more expensive. Looking over the study period, we find average class size conditional on level of course is fairly steady for most fields in the social sciences and humanities, in contrast to marked increases in undergraduate class sizes in engineering and biology.

Trends Over Time

We consider the average annual change in instructional costs for each of our 20 fields of study by looking at pieces attributable to changes in faculty salaries, class sizes, faculty workload, and other expenses. Across many fields, changes in faculty salaries and class sizes account for the bulk of the changes in instructional costs between 2000 and 2017. For instance, mechanical engineering saw a 2.10 percent reduction in cost each year, which is more than fully explained by an increase in class size. Costs for accounting rose by 0.64 percent annually, driven by faculty salary growth of 1.43 percent that outpaced increases in workload and class size. Some fields saw notable changes in faculty workload: education, English, and history all saw reductions in faculty workload over this period, which increased costs, while chemistry experienced a large increase. Only for nursing did changes in non-personnel expenditures increase costs. We also find appreciable declines in expenditures in a few tech-related fields, such as physics and computer science, perhaps reflecting falling costs for technology or lab supplies.

No Real Savings from Online Instruction

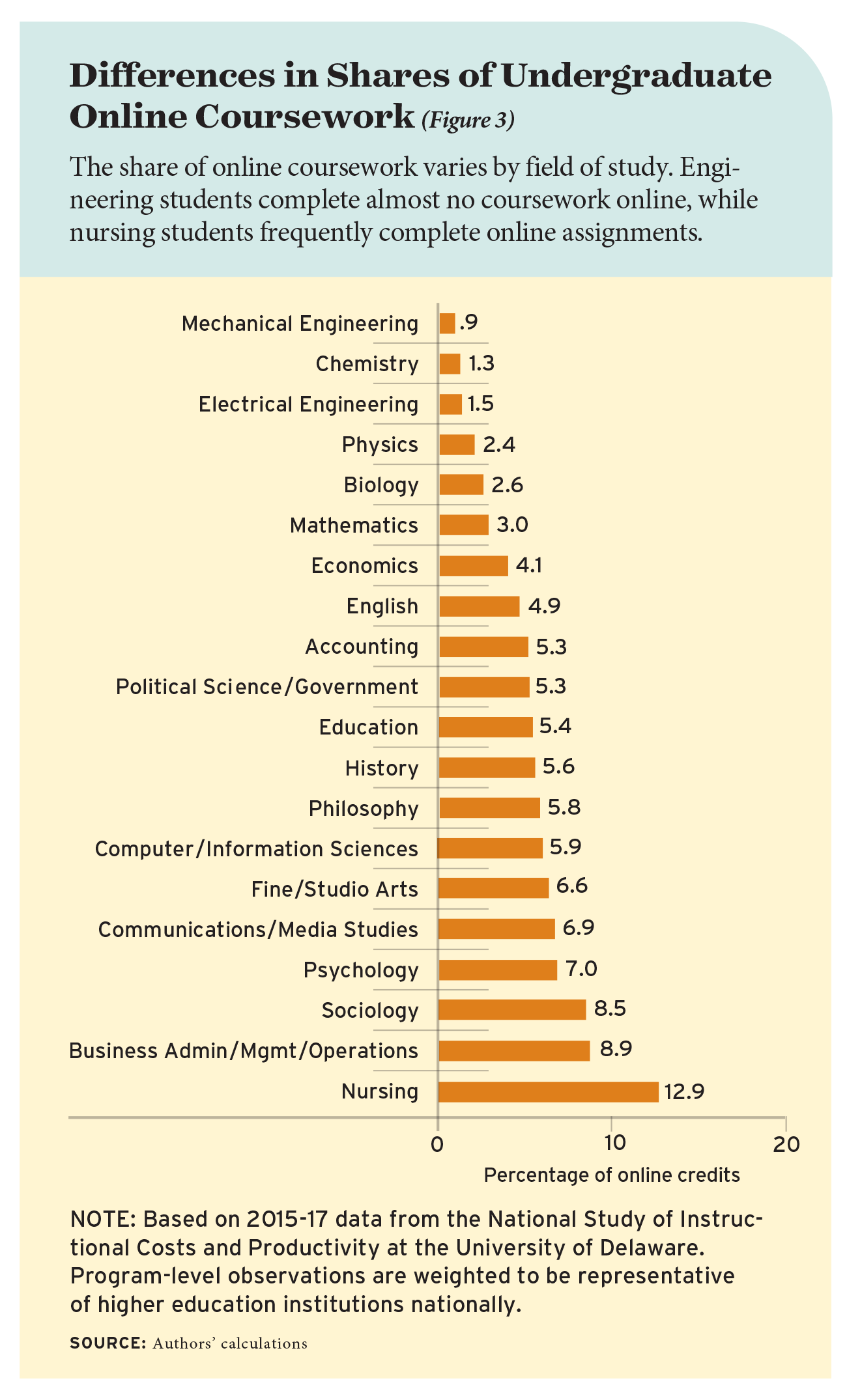

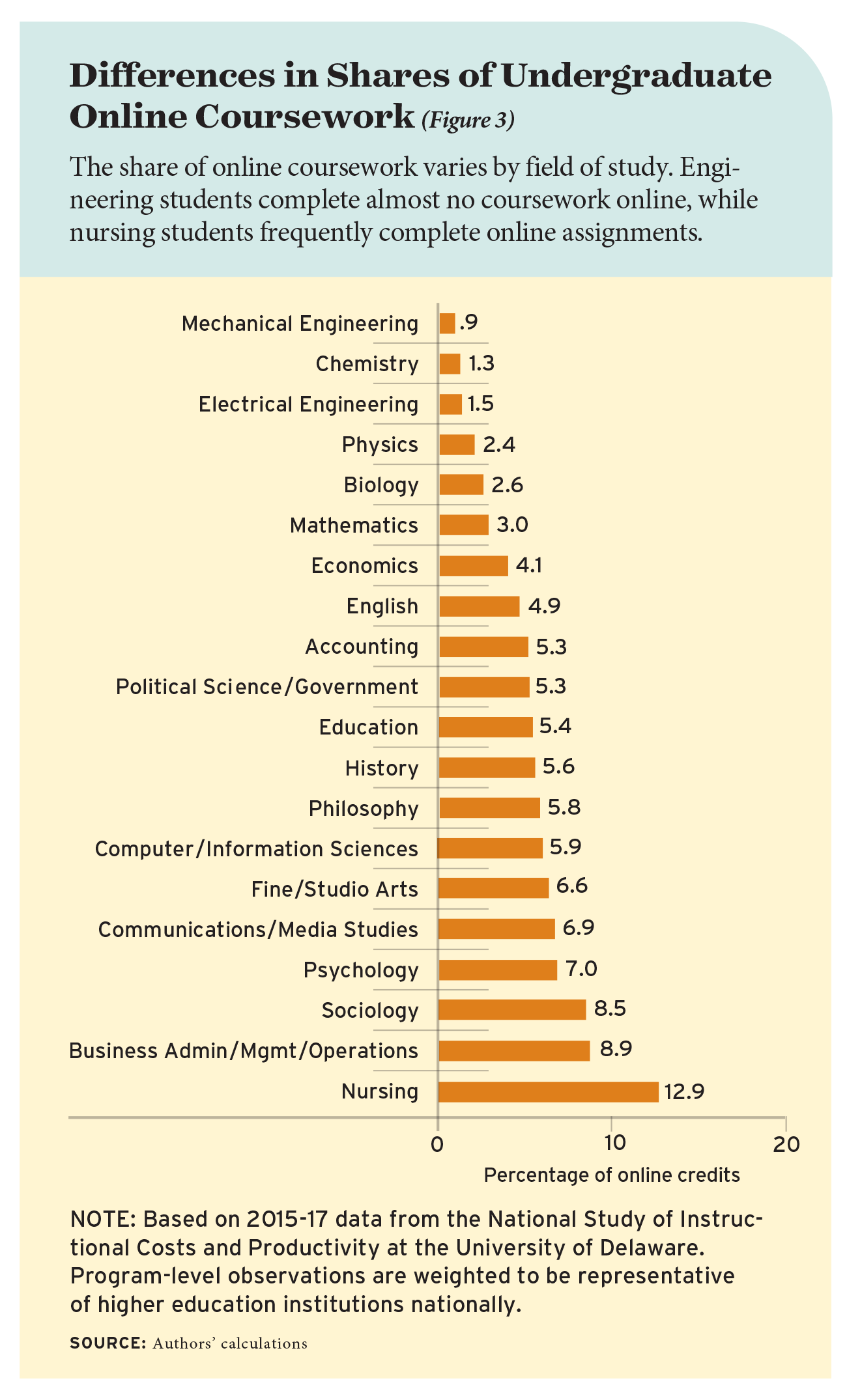

We then turn our attention to online instruction, which has commanded sustained interest from policymakers and institutional leaders as a possible strategy for containing college costs and expanding postsecondary access. We look at data from 2015–17 and find substantial variation in the prevalence of online instruction in the 20 disciplines we study. In undergraduate coursework, the share of online credits ranges from essentially zero in engineering to 13 percent of credits in nursing programs (see Figure 3). The average share of online credits is 6 percent, and 51 percent of the programs in our sample have no online enrollment at all. However, some graduate programs have considerable shares of online credits. For example, online coursework accounts for about one quarter of graduate education programs and one third of graduate nursing programs.

We investigate the potential cost savings of online classes and find a negligible association between online credits and instructional costs. Our estimates imply that adoption of any online coursework is associated with a cost increase of 0.4 percent, but an increase of 10 percentage points in online coursework is associated with a cost decrease of 1.4 percent. Neither of these is statistically significant. We view these estimates as small, especially given the hype about the cost-saving potential of online instruction.

A common hypothesis holds that online coursework can cut labor costs because such classes can be larger and require less face-to-face instruction. However, there is debate about the appropriate size for online courses relative to traditional in-person ones, with some institutions imposing lower enrollment caps for online courses than in-person study. We find some evidence that an increase in the share of undergraduate coursework completed online is related to lower salary costs. But estimates for the other cost drivers suggest that any short-run cost savings on salaries are offset by smaller class sizes and an uptick in non-personnel expenditures.

We note two caveats here: first, this analysis looks only at three years of data and thus cannot illuminate long-run cost changes that might emerge from the sustained adoption of online instruction; and second, we do not observe costs shared across departments, such as capital costs or costs for technology support. We also note the open question of whether the quality of online instruction is comparable to that of in-person classes, especially for less-prepared students. For example, a study by Stanford University’s Eric Bettinger and colleagues looked at a non-selective, for-profit school and found that students earned lower grades and were less likely to persist in school when they completed their coursework online. Some fields may find online education a more useful tool than others in lowering costs without compromising quality. Better understanding this potential is a productive path for future research.

Making Decisions at the Department Level

Over the past 17 years, average instructional costs per credit hour have increased only modestly. However, this relatively flat trend in average costs obscures variation in such cost trends by field of study. We find steep declines in spending in some science and technology fields, due to larger classes and increases in faculty workloads. Other fields, such as nursing, also saw declining costs that reflect a shift in the composition of faculty, with greater reliance on non-tenure-track staff. Yet other fields, such as business and accounting, have experienced escalating costs driven by rapid growth in faculty salaries. For all its promise, online education, arguably the highest-profile change to the delivery of higher education over this time period, is not associated with short-run cost savings.

Public debate about college costs usually focuses on differences between institutions. But the wide variety in costs by field of study should be part of that conversation too. It has important implications for institutional leaders facing decisions

such as differential tuition pricing and for government leaders considering programs to support more students to study engineering or nursing, for example.

Institutions have little control over the prevailing market wages for faculty, but changes in faculty workload, class size, and mix of course types across disciplines show some of the ways that costs might be kept in check. However, changes along these margins are also likely to shape research productivity and the capacity for public service. Thus, changes aimed at reducing instructional costs must balance potential effects on other valued activities of academic departments.

Our findings highlight the broad differences in costs and cost contributors among disciplines. We see a strong need for additional research that sheds light on the effects of instructor types, class sizes, and online classes on field-specific outcomes, including measures of quality such as student performance and success after college completion. For example, it may be that the adoption of online instruction reduces average instructional costs without impinging on quality in math but compromises student performance in chemistry.

Resource allocation decisions have strong effects on learning, instructional quality, and student outcomes, and these effects are likely to differ by field. Further research should explore these differences by discipline to help policymakers and institutional leaders work to reduce spiraling college costs while maintaining the quality of education that students strive to acquire.

Steven W. Hemelt is associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Kevin M. Stange is associate professor at the University of Michigan. Fernando Furquim is Director of Institutional Effectiveness at Minneapolis College. Andrew Simon is a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Chicago. John E. Sawyer is professor at the University of Delaware.

A longtime reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Maureen Downey, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss the efforts of Atlanta neighborhood Buckhead to break away and form its own city, how it failed and what it could have meant for Atlanta Public Schools and its students.

A longtime reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Maureen Downey, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss the efforts of Atlanta neighborhood Buckhead to break away and form its own city, how it failed and what it could have meant for Atlanta Public Schools and its students.

Joanne Jacobs, an education reporter and former San Jose Mercury News editorial writer and columnist, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss the

Joanne Jacobs, an education reporter and former San Jose Mercury News editorial writer and columnist, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss the  How expensive is a college degree? Usually, the answer is based on what students pay in tuition and fees compared to what they earn after graduation. As a result, policymakers often promote enrollment and applaud growth in tech-heavy programs that tend to produce high-earning graduates, like engineering and computer science—especially given the explosive growth in college prices, which have doubled in the past 30 years.

How expensive is a college degree? Usually, the answer is based on what students pay in tuition and fees compared to what they earn after graduation. As a result, policymakers often promote enrollment and applaud growth in tech-heavy programs that tend to produce high-earning graduates, like engineering and computer science—especially given the explosive growth in college prices, which have doubled in the past 30 years.