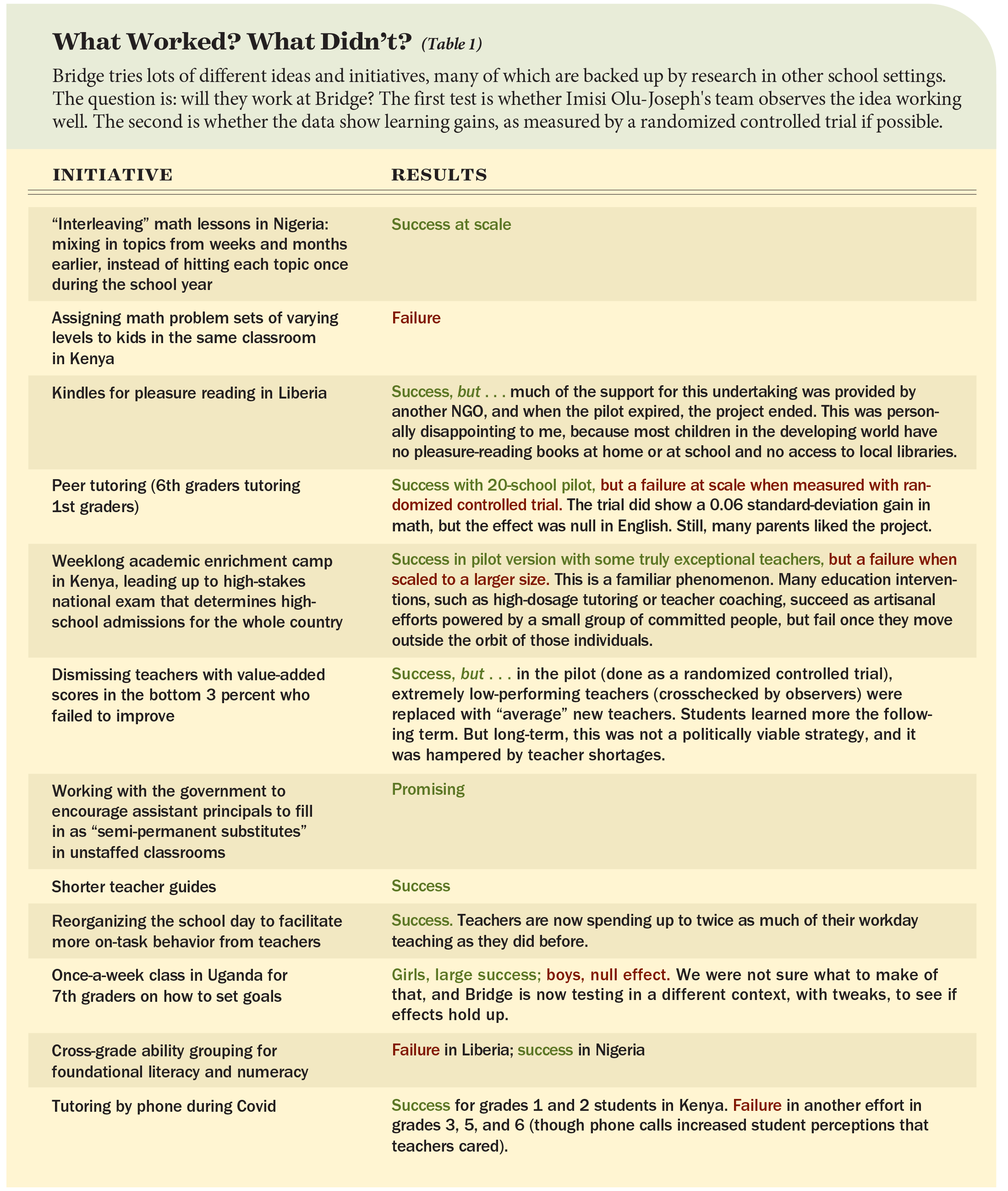

In April, an email from a Boston charter school ended a three-year saga.

“After much consideration, Roxbury Prep has decided to step away from the 361 Belgrade Ave site at this time,” Roxbury Preparatory Charter School wrote to its affiliates last spring.

The announcement ended the charter school’s quest for a new high school building in Roslindale, a neighborhood in southwest Boston, after Roxbury Prep encountered stiff resistance from parts of the community and some government officials. The site, 361 Belgrade Avenue, would have been home to just over 560 high schoolers.

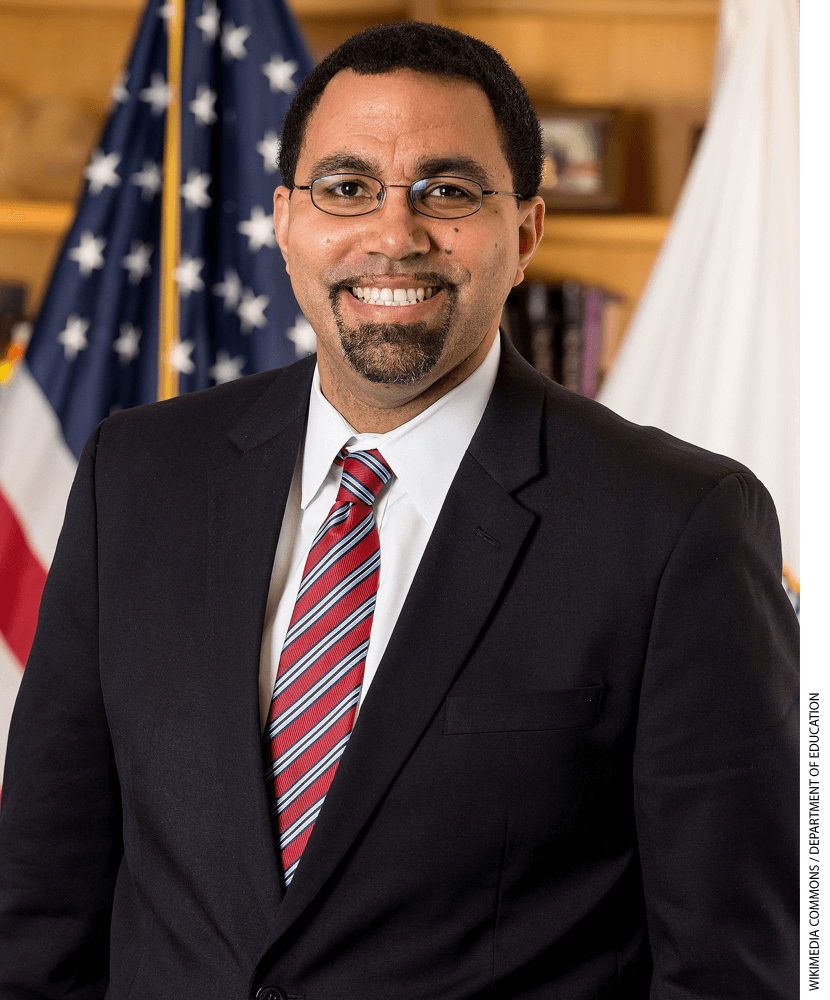

Roxbury Prep, which began as a middle school in 1999, was one of Boston’s first charter schools. In 2010, the charter school partnered with Uncommon Schools, a non-profit charter management organization that oversees 57 schools in the Northeast. Both Roxbury Prep and Uncommon have high profiles in the education-reform world: Roxbury Prep co-founder John King served as President Obama’s secretary of education, and the Uncommon Schools board includes Laura Blankfein, whose husband Lloyd was CEO of Goldman Sachs. The school was one of the Boston charter schools whose effectiveness in boosting student achievement was studied by an MIT professor, Joshua Angrist, who won the 2021 Nobel prize in economics.

Since 2010, Roxbury Prep has expanded, and in 2020 enrolled 1,568 students, split among three middle schools and two high school campuses. The prolonged and ultimately unsuccessful effort for the Roslindale site aimed to unite students at the high school, now divided between a former parochial school and converted office space five miles apart.

Charter schools are tuition-free public schools whose management has more autonomy than traditional district-run public schools. That can sometimes work to the advantage of students. When it comes to facilities, the autonomy can cut both ways. Charter schools may have freshly painted or carpeted buildings while public schools lack air conditioning. But while traditional public schools benefit from local tax and bond revenues to pay for new buildings and maintenance, many charter schools have to resort to more creative funding measures when they look for buildings or campuses to call their own. And while district schools have been on existing sites for decades, charter schools have to navigate approval processes for new buildings or to convert old ones. The space challenge is one reason that charter growth nationally has slowed, despite strong academic performance overall (see “Why Is Charter Growth Slowing?” features, Summer 2018).

When it comes to space, charter school leaders have to be “real entrepreneurs,” according to David Umansky. Umansky is the founder and CEO of Civic Builders, a non-profit charter school developer and lender addressing what the organization calls the “immediate need for charter school facilities support.”

That need has been on display in Boston. While thousands, residents included, supported Roxbury Prep’s site search in Roslindale, some neighbors opposed the project at 361 Belgrade Avenue, citing concerns over increased traffic and the size of the school. The fight over the site also got caught up in the city’s long-running racial tensions. Roxbury Prep’s students are 56 percent African-American and 40 percent Hispanic, according to state data. Advocates made a racial justice-related case for approving the site: “If black lives matter, city would hold a hearing for Roxbury Prep,” was a headline over an opinion piece by the high school’s founder, Shrada Patel, that ran in CommonWealth magazine, an online journal that covered the issue closely.

While Roslindale is 54 percent non-white, according to the 2020 census, 361 Belgrade Avenue was near a concentration of white households on the border with West Roxbury. Most of Roslindale’s Black and Hispanic residents live farther north and east in Roslindale, closer to the borders with Jamaica Plain, Mattapan, and Dorchester. In Mattapan, Dorchester, and Roxbury (where Roxbury Prep was founded), white Bostonians make up less than 30 percent of the populations.

It’s certainly possible that some of the opposition to Roxbury Prep was racially motivated. A September 2021 football game was cut short and police were called after Roxbury Prep players said they were racially taunted by an opposing team from a town north of the city. But a racial justice argument did not prove successful as a tactic to win approval for the Roslindale site.

After months of community outreach, in May 2018, Roxbury Prep filed a letter of intent with the Boston Planning and Development Agency to demolish the old car dealership on the site — which is zoned for a school — and replace it with a 96,000 square feet high school, designed for more than 800 students and complete with classrooms, a cafeteria, and a gym.

Six months later, the charter school filed a proposal for a much smaller school: just under 50,000 square feet for 562 students.

Finally, in April 2021 without a hearing before the Boston Planning and Development Agency, Roxbury Prep withdrew its proposal entirely. The average wait time for projects to come before the board was 83 days, according to a review Roxbury Prep conducted. Instead, the charter school waited for over 600 days.

City officials offered no explanation for the delay. Bonnie McGilpin, the director of communications at the Boston Planning and Development Agency, wrote in an emailed statement that the agency is “continuing to engage with the school” and that the agency remains ”committed to helping them find a permanent home that meets the needs of their community.”

The agency’s delay—and then-mayor Marty Walsh’s unwillingness to intervene—was likely the path of least resistance for the Boston government: a hearing would mean the city would have to declare a winner in the battle over 361 Belgrade Avenue. With tensions running high around the project, a decision either way would have provoked outrage. By not acting, the Boston Planning and Development Agency essentially forced an outcome—Roxbury Prep ultimately folding on the Roslindale site—while minimizing the political cost to Walsh, who is now the U.S. Secretary of Labor.

“Roxbury Prep is working in earnest to find a facility that our high school students deserve,” Uncommon Schools spokesperson Barbara Martinez wrote in an emailed statement. “We will announce our progress as soon as it is appropriate.”

Martinez declined to comment on a report from earlier this year that Roxbury Prep was looking into renting space from the Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology, a local non-profit college. Charter school site searches do sometimes fail, but Roxbury Prep’s effort in Roslindale took longer — and seems to have cost more — than most. The charter school had already sorted through more than 60 sites before settling on 361 Belgrade Avenue, Roxbury Prep reported. It hired two media consultants, including Dot Lynch, who had served as top spokesman to former Boston Mayor Thomas Menino. It hired, as a permitting consultant, the proprietor of the website bostonpermitting.com. It hired local counsel, a civil engineer, an architect, a landscape architect, a transportation planner, and an environmental/geotechnical engineer.

The tax return for Uncommon Schools shows that in 2020 it paid the property developer working with Roxbury Prep more than $550,000.

Even without holding a formal hearing, the Boston Planning and Development Agency collected over 2,900 pages of comments, the vast majority positive.

“My child can dream about college. But before that, we are all dreaming about the high school facility these kids deserve,” one Roxbury Prep parent wrote in an op-ed.

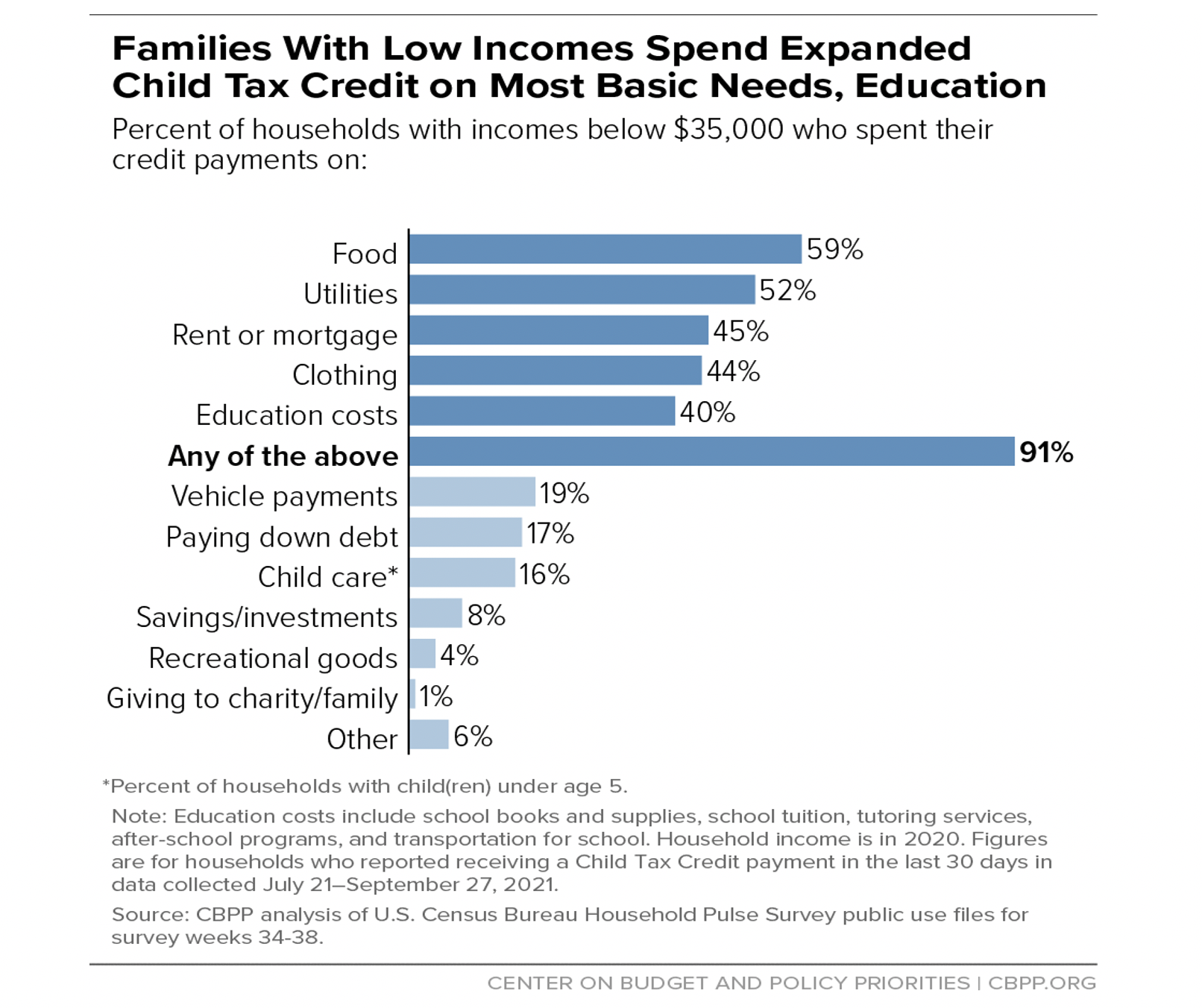

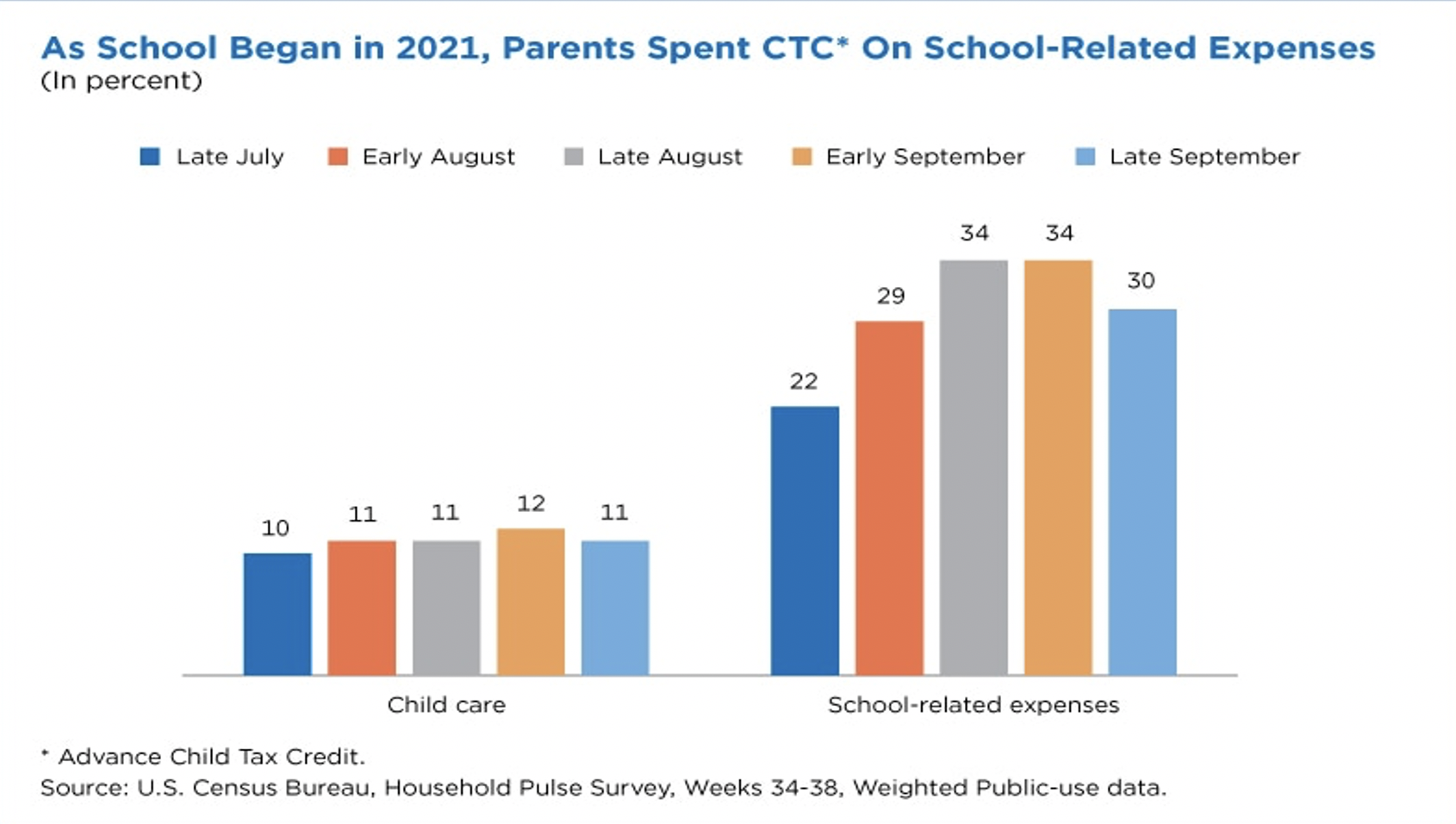

As of last year, 45 states and the District of Columbia offered some form of financial support for charter school facilities. Dozens of states now have provisions where charter schools have free or below-market-price access to vacant public school facilities. About a dozen states also have recurring direct per-pupil allocations for facilities. Many more have some form of grant or loan program, although several are dependent upon varying legislative appropriations. Federal programs, like the new markets tax credit, have also proved instrumental for charter school buildings.

The Center for Education Reform’s 2021 National Charter School Law Rankings & Scorecard includes a rank for facility funds and financing, with five points available total. Only the District of Columbia, Tennessee, and Minnesota have ratings above two. Twenty-eight states have a rating of zero. The District of Columbia, Tennessee, and Minnesota stand out because of their robust annual allowances, loan funds, and grants that go beyond just offering charter schools deals on empty buildings and access to tax-exempt financing. Massachusetts has a rating of one for its per-pupil capital needs allowances (included in regular per-pupil tuition revenue), and tax-exempt bond financing, direct loans, and guarantees for capital projects.

Charter schools have to track costs, transportation options, proximity to the neighborhoods they want to serve, play and exercise space, and quality of the school space when they conduct site searches. A principal at a traditional district-run public school will never have to worry about all of these details, let alone construction, Umansky, of Civic Builders, explained.

Robert “Bob” Baldwin, the managing principal of QPD, a real estate consulting firm in Massachusetts specializing in charter schools and nonprofits, said the first thing he does with a charter school is conduct a feasibility study. Baldwin goes through finances, real estate needs, and school governance with his client before looking at sites.

To make sure sites are sustainably affordable, Baldwin said he weighs the costs of the project as well as the school’s revenue streams from a per-student perspective.

“At the end of the day, you don’t want to put them in a building where their annual occupancy cost exceeds an affordable threshold,” he said. “In the city of Boston, and pretty much all Massachusetts, we use as a benchmark not going over 15 percent of the public tuition dollars. If in Boston a school got $20,000 per student, I would not want to see them paying debt service of more than $3,000 per student.”

As for capital costs, Baldwin said his benchmarks have risen, especially with rising real estate costs across Boston.

“I personally feel a little uncomfortable when I get over $60,000 per student in capital costs, or even over $50,000 to tell you the truth, but I’m kind of kidding myself these days if I think I can get under $50,000 in Boston,” he said. “We used to use $30,000 as a benchmark. But things change.”

Baldwin added, “It’s been really hard to find sites lately. What I might have paid a million dollars for 10 years ago I’ve got to pay 4 million for today.”

Residential real estate prices nationwide were up 13.6 percent in September 2021 over September 2020, according to Redfin, a real estate brokerage. The climbing prices delayed site searches as charter schools struggled to find affordable land, though the pandemic-related decline in demand for office space may work in schools’ favor. If charter schools found sites that fit their budgets, they still faced further delays from pandemic-related disruptions in construction and the supply chain.

Once a charter school finds a fitting site it can afford, it has to win governmental approval. In Boston, Baldwin said he almost always finds himself before the Zoning Board of Appeal in addition to the Boston Planning and Development Agency. The combination of the two, he said, means school operators need to plan for a six to nine month period of uncertainty “before you really know whether you can build something there.”

Charter schools also have to finesse municipal and neighborhood politics. Lots of people don’t want a school in their neighborhood because of the added traffic, Umansky said.

Baldwin put the traffic issue bluntly: “If you can’t stand up with a straight face in front of a skeptical crowd and try to tell them that, ‘We really do have a good plan for managing our people coming and going,’ then you should probably look for somewhere else,” since it’s the charter school’s job to propose and implement traffic plans.

Race and socioeconomic status also undergird debates over charter school sites, Umansky added, with discourse often beginning with “our kids” versus “their kids.”

All charter schools need to be prepared to “fight it out,” or work hard to educate communities by empathizing with local stakeholders, he said. When Civic Builders works with a charter school to find it a home, Umansky said he doesn’t try to call out the opposition but build strong enough relationships around the site search with neighbors, local leaders, and government officials to “get to a yes.”

Umansky called the practice “relational” instead of “transactional.” Yet, despite all of that work, charter schools often get told “no,” he said.

After that, charter schools “have to go right back to the drawing board,” Baldwin explained.

“I have clients say, ‘Well, we just spent 150 grand on design, can’t we just pick it up?’ No. No. Every place is different. You lose virtually all of your money to spend and you really do have to start all over again,” he said. The high sunk cost of a failed site search, both in terms of money and time (it takes years to get a new campus up and running from scratch), often pushes schools to keep working on impossible sites, Baldwin added.

Regardless of how heartbreaking a loss might be, charter schools have to move past it to the next opportunity.

In Boston, that’s where Roxbury Prep is right now: moving on. But it’s tough.

Mel Hines has three boys enrolled at Roxbury Prep — two juniors and one senior. She’s been a parent at the school for the past three years. I met her on the sidelines of a Friday night football game. The home team, the Randolph Blue Devils, had stands full of fans. Across the field, a handful of Roxbury Prep families cheered from two sets of bleachers. Even though none of Hines’ boys were on the field, she jumped up to cheer at every pause in our conversation.

“We need a building. All students need to be in one facility leaning on each other and learning together,” Hines said. “It’s unhealthy to have so many buildings to me, being a parent.”

The current high school set-up, with ninth and tenth graders on one site and the juniors and seniors at another, is less than optimal, she said.

“I wish they had more support,” Hines continued. “We go through a lot being a diversely mixed school, whether it’s from the games and being racially profiled or trying to keep the kids safe despite them being on separate campuses. If we had them in one place we wouldn’t have to worry about that. We need that kind of safety and community. We need more people advocating for us.”

Alfonza, a junior at Roxbury Prep and Hines’ son, said the campus divide affects student life, including the football team.

“There are people at both campuses so we aren’t one unit. Football has freshmen through to seniors but they can’t work together except at practice,” Alfonza said. “Some people [at the lower campus] feel that they’re alone. They don’t have people to lead them there.”

Keon, a senior at Roxbury Prep, agreed: “We’re more divided when we don’t have a building together. We’re just young Black kids trying to get out, but we’re getting pushed into Dudley [Street in Lower Roxbury], back into the ghetto. I just want people to know we’re good kids from good families and great homes.”

Yet, even as Hines lamented the school separation and the lack of amenities, she expressed gratitude for, and confidence in, Roxbury Prep. The high school, she reminded me, “has a great success rate.” (Roxbury Prep sent 98 percent of its inaugural high school class off to four-year-colleges or universities with $1.3 million in scholarships. That is light-years ahead of the comparable figure for Boston Public Schools, which says 52 percent of class of 2018 seniors who answered a survey planned to attend four-year colleges.)

“They send so many kids out with four-year college scholarships,” Hines said. “It’s bad not to have a building and not to be together, but if you make it to the end you could have a 4-year scholarship out.”

Hines hasn’t abandoned hope in Roxbury Prep’s site search either, which is actively on-going.

“What can you do if you give up?” she said. “You have to keep faith. Without faith what do you have?”

Cara Chang is a student at Harvard College concentrating in history.

The post Soaring Real Estate Prices, Vocal Opponents Complicate School Site Search appeared first on Education Next.

[NDN/ccn/comedia Links]

News…. browse around here

The director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, Rick Hess, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss the critical race theory debate, and how the media has covered the subject.

The director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, Rick Hess, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss the critical race theory debate, and how the media has covered the subject.

The president and CEO of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, Nina Rees, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss a recent report by the National Alliance which shows an increase in enrollment in charter schools across the country in the 2020-21 academic year.

The president and CEO of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, Nina Rees, joins Paul E. Peterson to discuss a recent report by the National Alliance which shows an increase in enrollment in charter schools across the country in the 2020-21 academic year.